Is Michael Phelps the greatest Olympian of all time?

- Published

- comments

Phelps wins record 19th Olympic medal

As Michael Phelps ducked his damp head on Tuesday night to receive the 15th Olympic gold medal of his phenomenal career, two of his supporters high up in the crowd frantically waved a home-made banner that read, in wonky script - Phelps: Greatest Olympian ever.

That gold in the 4x200m freestyle, plus the silver he had to settle for an hour earlier having led the 200m butterfly until the final fingertip, took his tally to 19 Olympic medals.

Undisputedly, Phelps is the most decorated athlete in Games history. But the greatest?

These are the sort of sporting arguments that lead, inadvertently, to the reputations of legends being trashed in a car-crash of comparisons. So let us seek a little clarity and calm.

Here in London, Phelps has won the simple numerical battle.

In his dust lie the totals of the woman who held the record for 48 years, Ukrainian-born gymnast Larissa Latynina (18 medals, nine golds); Nikolai Andrianov (the previously most decorated male, with his 15 gymnastic medals and seven golds); and the only swimmer to have got close, Mark Spitz (nine golds, a silver and a bronze).

Even someone as stellar as Carl Lewis (nine golds) can, by that basic rationale, only pale in comparison - which is why we must dig a little deeper.

While Lewis holds his place in history in part for winning medals in four different events, no other sports offer the same opportunities for multiple medals as swimming and, to a lesser extent, gymnastics.

It is not only the four strokes, but the relay combinations on top. Lewis was part of a wonderful USA 4x100m team yet relay golds only contributed two to his tally. Phelps has eight.

The 27-year-old from Baltimore has now won medals across three Olympics, just as Latynina and Lewis did. If we consider longevity to be as impressive as an eight-year blitz, then other contenders must come into play.

Sir Steve Redgrave won five golds over five Olympics., external Germany's Birgit Fischer won a remarkable eight, over six different Olympic Games, even having missed the Los Angeles Games entirely because of the Eastern Bloc boycott.

Hungarian fencer Aladar Gerevich won a little historical legroom of his own by taking medals in the same event six times. He even took gold medals 28 years apart.

And what of Al Oerter, winner of discus gold at four successive Games despite a car crash that nearly killed him, a man so obsessed with medals that when his doctor told him to retire on medical grounds he replied: "This is the Olympics - you die before you quit."

Numbers, you feel, can only take us so far.

Jesse Owens would surely have added to his four golds - and three Olympic records - from Berlin had a crass ban from US authorities and the global Armageddon of World War II not intervened.

So too would distance running pioneer Paavo Nurmi, winner of nine golds and three silvers between 1920 and 1928, who was excluded by officials from the 10,000m in Paris for health reasons and then banned from the 1932 Olympics for receiving a small amount of money in travel expenses.

Officialdom once again denied the wonderful Fanny Blankers-Koen, who after winning her four track golds at London's 1948 Olympics was then prevented from entering the high jump and long jump - at which she was world record holder - because athletes were only allowed to enter a maximum of four events.

By the time of her triumphs, too, she was already 32-years-old, robbed of the peak years of her career by the World War II.

There can be great meaning and triumph, great wonder, in far fewer medals than Phelps has amassed.

There is Ray Ewry - three golds in Paris in 1900, three more in St Louis four years later, two more in 1908 - having overcome polio and a childhood confined to a wheelchair.

There is Emile Zatopek, winning gold in London and three more in Helsinki including, famously, the marathon in his first ever attempt at the distance, and Daley Thompson, champion in the hardest event of all on two epoch-making occasions.

And there is Usain Bolt, the golden streak behind two of the most staggering performances in Olympic history and with the opportunity for more before this fortnight is out.

Being a great Olympian is about more than simple silverware anyway. There is sportsmanship, character, charisma and reputation.

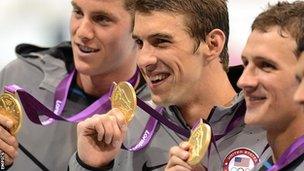

Phelps (centre) won his 19th Olympic medal in the 4x200m freestyle - his eighth relay gold

Phelps should not suffer in our eyes for being a bashful, low-key, East Coast kind of kid. Carl Lewis perhaps should for testing positive for banned substances three times before the 1988 US Olympic trials, and then reacting with a petulant, "There were hundreds of people getting off," when pushed.

Not for nothing did another great Olympian, Ed Moses, once say of his team-mate: "Carl rubs it in too much. A little humility is in order."

This is where the claims of others come to the fore. Redgrave remains the most modest of champions to this day. Blankers-Koen changed the world's attitude to women in sport.

Owens, who would later suffer the indignity of racing against horses to make ends meet, proved one of the Olympics' most fundamental truths in demonstrating, in front of Hitler himself, the emptiness of Nazi myth.

Despite his treatment back home he spent his later years travelling across the world as a US goodwill ambassador, and when the US decided to boycott the 1980 Moscow Games petitioned President Jimmy Carter not to sacrifice the Olympics in the name of political gain.

There is one more.

Muhammad Ali won gold in Rome as Cassius Clay, shocked the world again when he lit the cauldron in Atlanta 36 years later and was here in London, despite the ravages of Parkinson's, to welcome the Olympic flag during London's own opening ceremony.

Ali's most iconic moments in sport came outside the Games. Yet he remains the embodiment of their ideals, the most loved Olympian still alive.

The greatest? You take your pick. By comparing Michael Phelps to all these superstars of the past, perhaps the supreme accolade has already been offered.