Rio Olympics 2016: Five Olympics, five phases of Michael Phelps

- Published

- comments

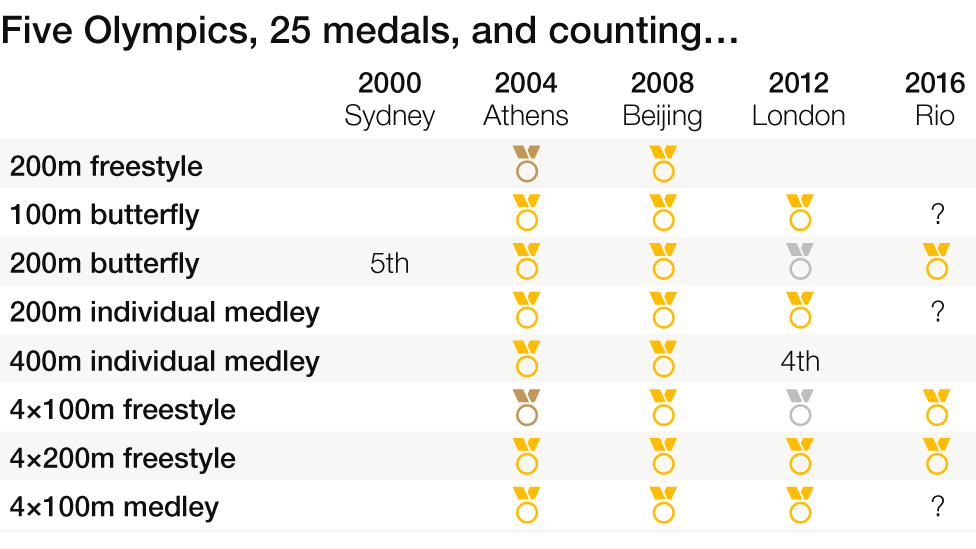

Twenty-one Olympic gold medals, more than twice as many as anyone else in history, maybe more to come.

With Michael Phelps it can all seem so simple, so pre-ordained. A swimmer defined by victory, a man who has always come through.

Except there has been nothing straightforward about the 'Fifth Act of Michael Phelps'. His 200m butterfly triumph in Rio's Aquatic Centre deep into Tuesday night may even have been miraculous. For this is a hero who had lost all sense of himself, an obsessive who had long ago begun to hate the gift that defined him.

The first three acts offered little to indicate the fall that would follow.

The 2000 Olympics, as The Kid - 15 years old yet finishing fifth in the 200m butterfly final, the boy with ADHD who had found his perfect focus, a world record holder before his 16th birthday.

Act Two, as The Freak - a 10,000-calories-a-day diet, a wingspan of 2.08 metres, hypermobile ankles, lungs twice the size of the average adult male. At those Athens Olympics he would lose the 'Race of the Century', external to Australian rival Ian Thorpe but win six other golds, a body designed for water, a boy in love with the pool.

The 2008 Olympics, and Act Three as The Superstar: eight gold medals,, external no records left standing, the world at his size 14 feet.

Phelps finished fifth in the 200m butterfly final in 2000 at the Sydney Olympics at the age of 15

And then, around the supposed happy ending of London 2012, Act Four: The Cynic.

It had begun in 2009, when a photograph emerged of America's clean-cut hero apparently smoking cannabis., external It continued through a three-month suspension, through missed training sessions, through a loss of the focus that had once seen him so fanatical he would count each stroke in every final, just in case his goggles ever filled with water and left him unable to judge the distance to the wall.

"I didn't care," he said later. "I wanted nothing to do with the water. Nothing."

Phelps still won six medals in London, four of them gold. But he was beaten in the 200m butterfly by Chad le Clos, the childhood fan turned adult assassin, and trailed home fourth in the 400m individual medley.

Retirement should have brought relief. It brought late nights and new friends, and another fresh start with long-term partner Nicole, but it brought no peace, and nothing to replace the one thing that had dominated every day of his life since the age of seven.

And so, like Thorpe before him, he began a comeback. And like Thorpe before him, he found the old magic hard to reignite.

Phelps won six golds and two bronze medals at the Athens Olympics in 2004

At the US Championships in the summer of 2014 he failed to win a single final. Then, driving home from a night out that September, he was stopped by police for doing 84mph in a 45mph area. A drink-driving conviction followed, accompanied by a six-month suspension from US swimming.

Rio? Rio couldn't have seemed further away.

"He had no idea what to do with the rest of his life," his long-time coach Bill Bowman told the New York Times.

"One day I said: 'Michael, you have all the money that anybody your age could ever want or need; you have a profound influence in the world; you have free time - and you're the most miserable person I know.'"

And so began the Fifth Act.

It started with six weeks in rehab at a treatment centre in Arizona called the Meadows. Phelps, one of the most famous sportsmen in the country, accustomed to the privileges and protection that come to that elite, was just another patient - going through the same group therapy, staying in the same spartan rooms, forced to confront a past that had become a burden rather than blessing.

Like Thorpe, Australia's most decorated Olympian, who had won three golds at his home Sydney Games and two more in Athens, Phelps had discovered that medals did not bring happiness. Neither did swimming, the one thing he could do, the thing he did better than any other man in Olympic history.

Former US President George W Bush congratulates Phelps on winning gold at the 2008 Beijing Olympics

It was something that appeared to afflict so many of those who, in the words of Australia's 1996 Olympic 1500m freestyle champion, Kieren Perkins, "spend six hours a day with heads in a bucket of water, looking at a black line."

Thorpe eventually admitted his own life-long struggles with depression, to his problems with alcohol and his adult thoughts of self-harm. Then there was his compatriot Grant Hackett, fifth in that Race of the Century, the third of them to end up in rehab, the third to lose himself in a stalled comeback.

At the Meadows there was a small pool. Because water had always been Phelps' sanctuary, he was instinctively drawn to it. But wasn't swimming the problem? Didn't that gaping hole in his life need filling with something else?

"The problem for me was I just didn't have enough balance in my life," said Leisel Jones, who won nine Olympic medals for Australia before herself succumbing to depression in young retirement. "I didn't have anything else, and that was terrifying for me."

Phelps is the most successful Olympian ever with a staggering 21 gold medals

Phelps began to look. He made fresh contact with his estranged father Fred, with whom he had not spoken since 2004.

He committed to Nicole, and to a long-term future together. He read self-help books, and then, with the help of Bowman, took the biggest decision of all: to commit to swimming again, at an age when Thorpe was long gone, to chase another Olympic gold even when there was no chance his tally could ever be threatened.

In doing so he fell back in love. Swimming, first a gift, then a burden, began to inspire him again.

With that inspiration came some of the old speed. With fresh focus came the old speed. A body that had held 13% fat in London dropped that to just 5% for the shot at Rio. Training harder than he had since Beijing eight years ago, he made the Olympic team. People began to talk, and then believe: could the man who had gone where no other Olympic athlete ever gone, go further still?

Bowman remained a constant. With fiancee Nicole came a son, Boomer.

But this is not the old Phelps, who would push anything and anyone away who could possibly distract him from gold.

Nicole and three-month-old baby boy Boomer have been in the stands to watch every one of his races in Rio

Here in Rio he is happy to be distracted. Nicole and Boomer have been in the stands here for every race he has swum. Swimming is still there, but in Act Five, there are more precious things at the centre of his world.

"I never thought that he would ever change." says Bowman. "He hid everything that makes him human for 12 years."

Phelps is still as competitive as ever. You could see it in his reaction when he took revenge on Le Clos for that shock defeat four years ago: sitting astride his lane marker, arms outstretched, hands beckoning as if daring anyone else to come and have a go.

Yet as he walked round the pool decking after that first gold on Tuesday night, 4x200m freestyle relay gold still another hour away, there was something else, too.

It wasn't just the clenched fist he waved at the stands, or the way he made his way through the photographers to where Nicole and his mother Debbie were standing to take three-month-old Boomer in his arms.

It was the huge smile, the unguarded emotion of a man who is genuinely happy, the sight of a man finally at peace.

In the Fifth Act of Michael Phelps, he is The Reborn.

- Published10 August 2016

- Published18 August 2016

- Published3 August 2016

- Published19 July 2016

- Published3 August 2016