Rio 2016: Usain Bolt, Wayde van Niekerk and Team GB shine on 'impossible' night

- Published

- comments

We are used to Usain Bolt pulling off the impossible. On Sunday the impossible almost happened to Bolt: being upstaged on the night of his Olympic 100m final.

Not by a rival from the blocks alongside him. The world has not reversed on its axis nor the stars dropped from Rio's night sky.

There was a tectonic shift all the same: a record detonated that many thought indestructible, a new hero confirmed who may help fill part of the chasm that will be left when Bolt finally jogs away from this sport and into our giddy memories.

Wayde van Niekerk is no ordinary athlete, and not just because he is coached by a 74-year-old great-grandmother. In winning gold at the World Championships a year ago he got to within 0.30 seconds of Michael Johnson's 400m world record set 17 years ago.

But that is like saying you have climbed Everest when you are sitting round a camp fire at base camp. To break that record and run 43.03 seconds as he did in Rio is jogging up to the summit without oxygen.

To do it from lane eight, blind to the forces pushing you on from inside, alone with the lactic and the fire in your lungs, adds another rich layer of wonder. To athletics fans, Bolt's defeat of Justin Gatlin 25 minutes later could only be an anti-climax.

It tells its own tale of the Jamaican superstar's hold on the watching world that he will still own the front pages and win the popular vote in a golden landslide.

It was not a thriller of a final. The man who everyone knew would win won. The triptych could never really be in doubt.

At this late stage in Bolt's sprinting curve it is like watching a greatest hits tour: we know all the moves, we can all sing along with the hits, we all know how the encore goes.

It should draw nothing from this night and nothing from the cumulative wonder of the past eight years.

Three Olympic 100m finals, three Olympic 100m gold medals. Bolt goes where no-one has ever gone before. No-one has ever relished these nine-point-something seconds of intensity like this man nor flourished so much within them.

The age of Usain has been like nothing else the Olympics can offer. From above, the stadium is a little bowl of white light in dark city; inside, with the world watching, the silence is so sudden when the sprinters crouch that all you can hear is the rhythmical chopping of helicopters overhead. The stands glimmer with the firefly glow of 50,000 mobile phones.

It is too much for some. Justin Gatlin, just as he did at the Worlds a year ago, owned the first 20 metres but lost the critical last 20 as his muscles seized and form collapsed under the knowledge of what was coming up and past him two lanes to his right.

Had the controversial American run the same time he managed in the US trials, or even in the final in Beijing, he would have stolen his second 100m Olympic gold.

Then again, had he got faster, Bolt would most likely have gone fast enough all the same.

With 9.69secs in Beijing and 9.63 in London, 9.81 here in Rio might not seem so remarkable, but that is because we have all been sweetly duped by an unprecedented outlier.

When Gatlin won his 100m gold in Athens he did so in 9.85. Maurice Greene won in Sydney in 9.87, Donovan Bailey in Atlanta in 9.84.

So 46 days after tearing his hamstring, with a turnaround of just over an hour from the semi-finals, Bolt could still make all this appear easy.

In the aftermath of it all he found Van Niekerk still wandering round with his hands on his head and wrapped the younger man up in the fastest hug in history; in that embrace were the world records for the 100m, 200m, 400m and 4x100m.

Van Niekerk, a passionate Liverpool fan, had prepared for this final by watching Sunday's 4-3 win over Arsenal.

When he came to run there was no chance of anyone closing up on him as Arsene Wenger's men had at the Emirates. These were his splits across each of the 100m he ran: 10.7 secs, 9.8, 10.5, 12.0.

You don't catch that, and you can't match the impact it made. This was a 17-year-old world record, in an event that has seen its best broken only four times in 48 years.

The only comparison you can make is with David Rudisha's stunning 800m record set in London four summers ago, another one run alone out in front, another one on the same night as Bolt held the world's stare.

For a British audience watching on from thousands of miles away, it added to the unreal dizziness that had already taken hold of the weekend.

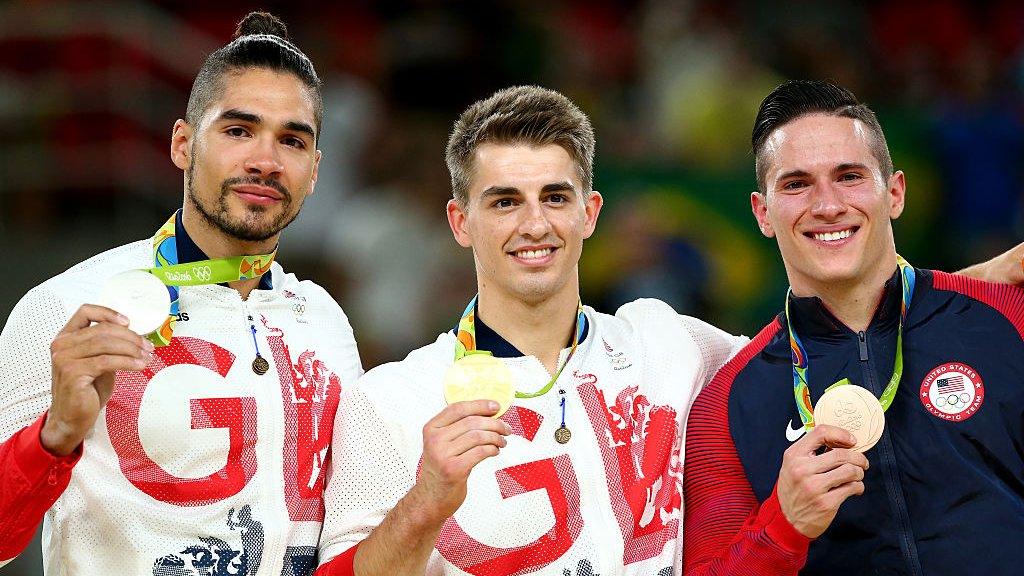

On Saturday Team GB had won three golds, four silvers and a bronze. Between 18.30 London time on Sunday and shortly after midnight they won five more golds, from Justin Rose at the golf course in Marapendi to Jason Kenny in the velodrome, Andy Murray in the tennis stadium and Max Whitlock - twice - about 200 metres away the Olympic Park in Barra.

It made it Britain's most successful day ever at an overseas Olympics, and knocked several consecutive decades of toil into stunning contrast.

In the 16 Olympics from 1928 to 1996, only once did Britain win more than five golds in an entire Games. Until the giddy madness of London 2012, not since 1908 had GB won five in a day, and that was at a Games so unrecognisable it included tug-of-war and real tennis.

From Super Saturday Britain's athletes appeared to have upgraded to This Is Getting Silly Sunday. It was the Weekend of Wonder, not just a few special hours but the Great 48.

Britain has never before won a gold in men's gymnastics. After Whitlock's two in two hours, a few made that hoary old comparison to waiting for a bus and then two coming along together.

This was more like waiting for a bus and then two spaceships arriving at once. In the very recent past, the idea of a British male winning Olympic gold on either the pommel horse or floor was not so much a stretch as unimaginable.

So too were the deeds of Bolt, and the one-lap wonder of his young apprentice. One Sunday brought them all - maybe the most impossible thing of all.

- Published15 August 2016

- Published14 August 2016

- Published14 August 2016

- Published15 August 2016

- Published18 August 2016

- Published3 August 2016