Tokyo Olympics: Why women are leading the way for Scotland

- Published

Olympic Games on the BBC |

|---|

Hosts: Tokyo, Japan Dates: 23 July-8 August |

Coverage: Watch live on BBC TV, BBC iPlayer, BBC Red Button and online; Listen on BBC Radio 5 Live, Sports Extra and Sounds; live text and video clips on BBC Sport website and app. |

Laura Muir, Jemma Reekie, Katie Archibald, Kim Little, Caroline Weir, Seonaid McIntosh, Polly Swann. Many of Scotland's Olympic medal hopefuls - and biggest names - are women.

In fact, 60% of the 53 Scots going to Tokyo are female. That represents a significant milestone in the modern make-up of the team, with Great Britain and Northern Ireland's squad taking more women to an Olympics than men for the first time in 125 years.

It's reflective of a growth in women's sport in the past few decades, but how did we get to this point?

More Scots, and more women

The number of Scottish women going to Tokyo stands at 32 - compared to 21 men - which is a big leap from the past two Olympics.

In Rio five years ago, there were 47 Scots with 46% of them female. In London in 2012, there was one more female athlete (26) than male (25).

So, while the number of Scots making up Team GB has roughly stayed the same in the past decade, Tokyo represents a sizeable shift in the gender balance.

But it's not just the number of women in the team that have changed, but the profile too. Whether it's Liz McColgan, Yvonne Murray, Shirley Robertson, or Katherine Grainger, Scotland has always produced successful female athletes.

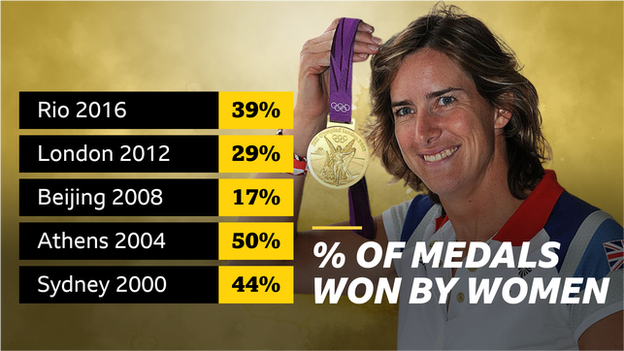

However, historically men have won a greater percentage of Scotland's medals, even at the most recent Olympics when the gender balance of the squad was much more equal. Women accounted for 29% and 39% of Scotland's medals in London and Rio, respectively.

But with the majority of Scotland's medal hopes resting on women this time, Tokyo could be only the second Games since 1928 in which they win more medals than men.

Role models & culture shift

The exponential growth in funding for elite sport in Britain over the past 30 years has led to greater opportunity for women. Increased funding means more numbers, which helps to breed confidence and competition.

"One of the things I think was really important was having strong female role models," Olympic track medallist Eilidh Doyle tells BBC Scotland.

"In athletics, for so long Lee McConnell was the only [Scottish] female athlete in the senior teams and she was the person I looked up to. Then in London 2012 it was all females for the athletics team.

"I think just having other females there to see it's achievable has an element to play."

Role models are important, but there are other challenges that can hold female athletes back.

In 2015, Scottish Swimming identified that, while more girls than boys were swimming in clubs, there was a lack of women coming through on the international stage.

In a bid to change that, they started 'Project Ailsa', which changed the way they treat female athletes, and now three of the five Scottish swimmers going to Tokyo are women, with a strong contingent at junior level.

"We started to treat females differently to the way we had before, which was just to lump them in with the boys and to treat everybody as one group," Scottish Swimming national coach Alan Lynn explains.

"It's not about hiving them off into single sex groups - but separating the girls off for a couple of sessions or a camp, and giving them their own social time and space.

"Taking just girls away to a competition changes the dynamics of everything - meal time, social time, at the pool side supporting each other and of course the interaction between coaches and athletes.

"When women swim well in the pool, I'm not sure we can claim credit under any particular initiative. But if they're there, sticking around; if they're happy and swimming faster, that gathers momentum all by itself."

No room for complacency

Increased funding and a culture shift in some sports have helped and the coverage and visibility of women's sport has never been greater. But there are still barriers that mean gender balance in the future is far from guaranteed.

Doyle, recently retired, says there is an assumed "expiry date" on female athletes when they reach 30, as she fought to keep going amid questions from sponsors despite being in the form of her life.

Then there is the growth of social media, which has allowed all athletes to take control of their own messaging, but presents other challenges.

"Now it seems to be that sponsorships or contracts are based on followers," Doyle says. "Influencers and stuff have come into play. You need to be a model almost to do this sort of stuff.

"I think that's really hard. A lot of athletes just now - and predominantly females ones - feel like they have to sell themselves in order to get sponsorships and things like that."

There is also the continued challenge of keeping participation high among girls at school, which is often more difficult than it is for boys.

Ailsa Wyllie is a former Scotland hockey player and now leads Sportscotland's women and girls programmes. She says one of the main barriers is a lack of confidence, with girls' participation in sport dropping off when they reach secondary school.

"It's not confidence in their sporting ability but confidence to turn up to something," Wyllie says. "A lot in that age group is peer pressure. You get groups where there's a ringleader who doesn't go and that has a major influence.

"Confidence is also married with their body image. The changes girls go through at that age have a significant influence on how they feel about themselves. Social media has taken that to another level."

Through the Fit for Girls programme in schools, Sportscotland is trying to ensure girls' initial experience of sport is a positive one. And, at elite level, confidence is high for those women off to Tokyo.

"People are not just making teams now but want to go to the Olympics and be on the podium and medal," Doyle adds. "Having that confidence and to believe that's possible is really important."