Katherine Grainger: 'It's not fair, it's not how life should be'

- Published

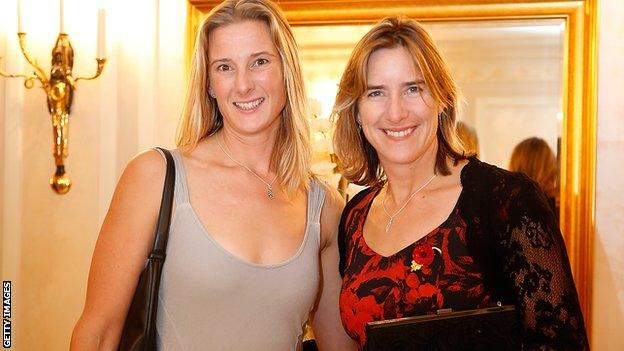

Sarah Winckless and Katherine Grainger won the world championships together in 2005 and 2006

Their friendship was forged on the river in the good times and endures now, more than 15 years later, in the bad times.

Rowers Katherine Grainger and Sarah Winckless were gold medallists together in the world championships of 2005 and 2006, half of an all-conquering quad in Gifu, Japan and on Dorney Lake in Eton. The memory of it has never faded.

They are together now, not so much because of their shared life in a boat, but because of what has happened since.

Winckless looks the epitome of health and vitality, a striking woman of 40. But the truth is that some years ago she was diagnosed with Huntington's disease, an incurable, hereditary condition that begins with slurred speech, involuntary movements and loss of temper, and then descends into a paralysing dementia.

A child of a Huntington's sufferer - Winckless' mother has it - is rated 50-50 at having it themselves.

There are four children in the family and she is the only one with the condition. One out of four. It's a good result, she says. Of sorts.

The rowers are in Glasgow to promote awareness of the disease through the Scottish Huntington's Association., external This is a grim subject but listening to Winckless - a bronze medallist, external at the 2004 Olympics in Athens - and her Olympic champion pal is far from morbid.

Sarah Winckless and Katherine Grainger, along with Frances Houghton and Rebecca Romero, win the quadruple sculls at the world championships in Japan in 2005

They are an engaging double-act, a breathless flow of stories and laughter and, of course, in Grainger's case, support.

"That's why, when athletes talk about the friendships they've made, it's really hard for normal people to understand the depths of it," explains Grainger.

"When you're rowing together, you're doing everything together. You spend so much time in each other's company.

"There's nowhere to hide. You see people at their most elated but often you see people at their lowest and it's genuinely blood, sweat and tears. It's not a cliché, it's real. There's exhaustion and disappointment.

"People see it publicly every four years and they see the best weather and the athletes at their physical and mental peak, but it takes four years to get to that point. Four years of the opposite.

"The reality is that it is never good enough for four years. Before you get out of bed you are exhausted and then you drive to training. And in an outdoor sport you are out in the depths of winter, you've got the lights on in the car because it's pitch black outside, you chip the ice off the windscreen and then, stupidly, you jack the heaters up so your little car is like a warm oven when you arrive at the water. And then you have to get out and you don't want to. And that's how we bond because not everyone will understand what we do."

Winckless laughs at the description, adding: "Your partner can't understand it. They're next to you on the journey but they're not with you on the journey. When we started we used a scout hut under a bridge as a clubhouse. Our boats were on scaffolds. It was very, very basic, but for us it was home. No creature comforts. Cold and muddy.

"We were going to the bakers and begging for old bread that we'd have in our hut. And we were privileged because our predecessors had it worse. They had no lottery funding and were coming out of it in huge debt."

Rebecca Romero, Sarah Winckless, Frances Houghton and Katherine Grainger after the medal presentation at the world championships in 2005

When Grainger heard that her friend had been diagnosed with the disease she found it hard to figure it all out.

"It doesn't chime because here is somebody who is fit and healthy and strong and has an amazing personality, and she has this cruel and crippling disease," said the 38-year-old Scot.

"It doesn't make sense in my head. It's not fair, it's not how life should be. She's perfect and I can't imagine her not being the way she is right now.

"What brings it home is that I know Sarah's mum really well and that's reality and that's somebody in a wheelchair and not able to communicate. And the fact that that's a potential outcome for Sarah does not compute. Sarah handles it so well. We rage at it and we're angry and we don't want to lose our friend, but she copes better than anybody."

Grainger's own dilemma is a dot on the landscape by comparison, but her career and whether she's retiring or carrying on to Rio in 2016 is a subject that never goes away.

"I get asked all the time," she laughs. "Taxi drivers. People on the street. They say 'What are you doing these days? Are you still a rower?' I'm in my own massive crisis in my own little world. In all honesty, I haven't decided what I'm doing.

Sarah Winckless and Elise Laverick with their bronze medals from the double sculls at the Athens Olympics in 2004

"The deadline was last September but I couldn't come up with an answer. I met with the decision-makers in British rowing and I was very honest. It takes over your life and your commitment has to be absolute. If I'm in, I'm in. I don't want to go back just to get the kit. I want to go back and get the gold medal.

"But I know what that would take. It's such a huge commitment and such a precarious thing. You're in a team and if anything happens to one of those people, then it's game over. That's the thing about team sport, you put your hopes and dreams in others and that's why the bonds become unbreakable, but it's also a risk.

"At the moment I have this lovely story from London 2012 and this very happy ending and do I want to compromise that by coming back and not winning again?

"The public see great Olympic moments but we'll spend four years being told, and believing, that we're not good enough. The biggest fear in professional sport is complacency. Coaches play with that all the time."

That said, she has missed racing competitively. Missed the feeling, if not the training.

"There is something quite magical about being out on the river, but things get very rose-tinted after a big success and now I don't remember a bad day in four years," admits Grainger. "It was marvellous. The mind plays tricks. But I know if I go back in a boat the first few months are going to be horrific.

Grainger won Olympic gold at London 2012

"But the other thing is that another gold (in Rio) is possible and it's hard to think I would chose to walk away from it. I'd have to live with that decision.

"Everyone who is sensible and smart and whose opinion I would respect all say it's a risk. You're risking your reputation and leaving on a disappointment. That's what they say. So I don't know. But I'm going to need to know very soon."

All of that is familiar to Winckless. She had her own dilemma when choosing to retire in 2009., external Has she advice for her mate?

"One of the greatest strengths of our friendship is that we know when to talk and when not to talk," she laughs.

In other words, you're on your own with this decision, Katherine.

Winckless, on the other hand, is far from alone.

"Sport has definitely given me resilience and resilience helps when you've got a disease like this," she says. "There were times when I've looked down the well and feared about what is going to happen to me, but I'm a positive person. I've always had to be. And I'm not stopping now."

- Published26 January 2014

- Published3 August 2012

- Published5 April 2019