How revolution at Leander Club led to British rowing success

- Published

Sir Steve Redgrave and Sir Matthew Pinsent are just two of the rowers to have been based out of Leander's Victorian Clubhouse

124 Olympic medals, two knights of the realm plus countless other honours besides. It's a record any club in any sport would be proud of.

But the success brought to British rowing at club and international level by Leander Club might not have been possible without a revolution which sparked a golden age in the sport.

The so-called 'Pink Palace Revolution' at Henley-based Leander in 1983 changed the course of rowing on and off the water in Britain, as the sport opened its doors to anyone with gold-winning potential and moved away from being a place for privileged gentlemen.

The shift created a conveyor belt of men and women gold medallists for Team GB and Leander became home to household names in the sport, including Sir Steve Redgrave, Sir Matthew Pinsent, Debbie Flood and Vicky Thornley.

Leander is 200 years old, but it arguably had to wait 165 years to experience its most significant success.

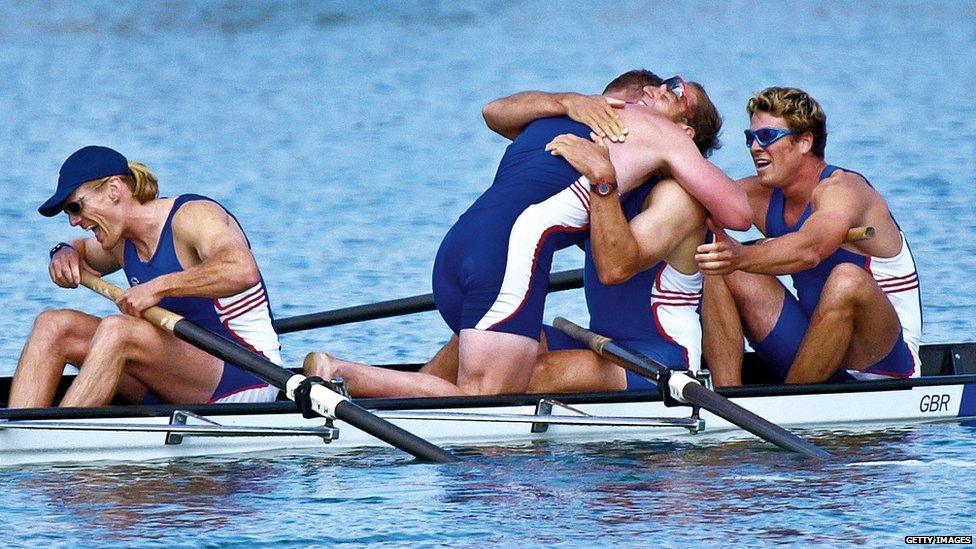

Sir Steve Redgrave (centre right) is hugged by team-mate Matthew Pinsent after the GB crew won the gold medal at the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000

In the early 1980s, Jeremy Randall and a group of "rebels" were campaigning against an old-guard committee to turn around the club's struggling finances and deteriorating Victorian clubhouse.

"The club was run by extremely nice, high-powered, establishment figures many of whom had had a great deal to do with rowing at the highest level, but life was changing," said Randall, the now president of Leander.

"Oxford and Cambridge were no longer the great centres of rowing. The clubs were overtaking the colleges so we needed to change.

"We simply needed to trade in a more business-like manner and to wake up to what was happening towards the end of the 20th century."

The committee's plan was double member subscriptions to solve their financial woes, but Randall and others wanted to propel Leander into the modern world.

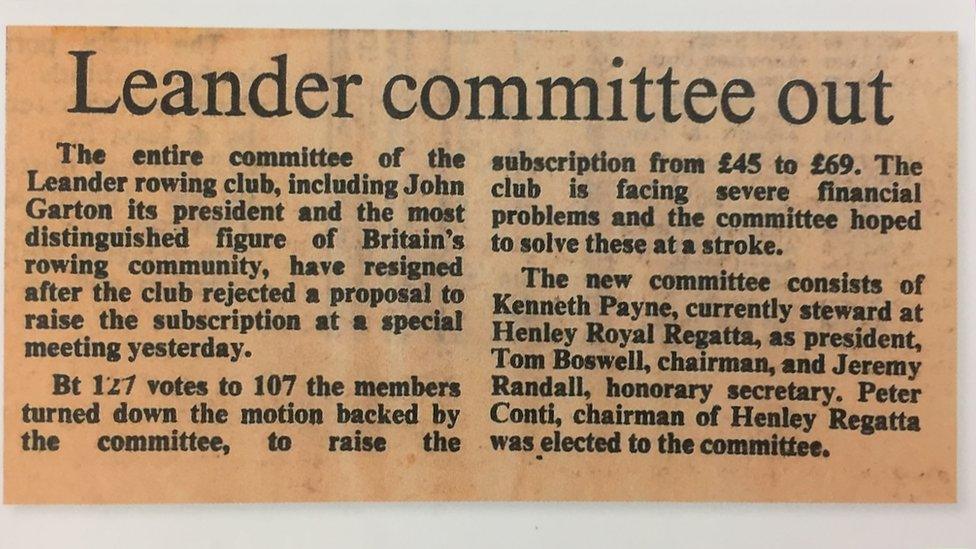

When the committee resigned after their motion was rejected, the "rebel group" was thrust into the hot seat - a story which made the front page of The Times.

The news of the committee's resignation hit the headlines

The issues which created the heated disputes were down to the state of the club's finances, mismanagement and the question of female membership.

A driving force in the rebel faction, the late Peter Coni, a former chairman of Henley Royal Regatta, said the committee was "out of touch" and that female membership was "essential".

Commercially-minded, the new committee overhauled the club's finances with associate membership, sponsorship deals and began to reinvest in its rowers.

As finances improved and the club's clubhouse was revamped, a resurgence of success on the water followed through the arrival of fresh-faced Redgrave from Marlow.

Success at Henley Royal Regatta and his gold medal as part of the coxed fours at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles led to the arrival of an 18-year-old Pinsent and the start of a partnership which would create history in British rowing.

"It's just impossible for me to imagine what my career would have been like without Leander," said Pinsent.

"They were a force then just as they are now. There are sort of a preeminent club force, the most successful at producing Olympians and Olympic champions.

"It's a place that if you want to win... this is where you come to.

"Not many people can do it, not many people can create this sort of atmosphere."

The club was the base for the Redgrave-Pinsent partnership to blossom as Jurgen Grobler, currently Team GB's men's coach, joined Leander as their director of rowing in 1990 and instilled a method of success which inspired the national rowing team.

Jurgen Grobler joined Leander in 1990

Sir David Tanner, who was British Rowing performance director for 21 years, recalled how Leander "were ahead" of Team GB by having an established training programme and a professional coach in Grobler when he set out to form the national squad in 1996.

"If they (Leander) hadn't done what they were doing, we would have found it much harder to kick off the national team concept, without question, but that was only men, it's wasn't women," added Tanner.

Pinsent recalls how, when Grobler arrived from East Germany, he received surprising reports from fellow rowers about his approach to training.

"We used to go out (before Jurgen Grobler arrived) on Saturday and Sunday to race against one another. There was two plastic chairs that were by the showers because by Sunday lunchtime there were people who couldn't stand up in the showers," Pinsent said.

"But then Jurgen came along and looked at this and went 'This is mental, what are you doing?'"

Training soon changed as Leander's squads started training twice a day and rowed for longer distances at "really low intensity" - a stark contrast to what the athletes were used to.

But perhaps the coach's boldest move was to change Pinsent to stroke, and move Redgrave behind him - something which the latter saw as a "slight" to begin with.

"How Jurgen sold it to him I've got no idea," added Pinsent. "For me it was a big step up.

"It became evident fairly early on that the boat was going quick and so at that point that gives you confidence, and you're thinking when it comes to a trials race... that we can do alright here, we can win."

Pinsent and Redgrave at Leander Club in 2000

The change worked, the pair won gold in the coxless pair at the Barcelona Olympics of 1992 and the effect of the 'Pink Palace Revolution' was in full flow.

National Lottery money followed to develop the club's facilities and a women's training programme was established after membership was granted in 1997.

Tanner, a Leander and Molesey rowing club member, said the club were a "very big asset to work with".

"In the period between 1996 and 2000, they were ahead of us," he added.

"When I took over in 1996 I had two and a half staff and no base, and no development programme or anything. All of that has come through lottery funding in my time.

"Leander were there. They were doing what they had always done and that's why Steve and Matthew went there because there was nowhere else to be."

Leander's success on the Olympic stage continued with many of its athletes, including Flood, James Cracknell, Peter Read and Will Satch, to name but a few, led the club to call itself the "best in the world".

Sir David Tanner said Leander "were ahead" of Team GB in the early 1990s

Redgrave finished his career after winning gold medals at five consecutive Olympic Games from 1984 to 2000. Three of medals were won alongside Pinsent, who went on to secure his fourth consecutive gold at the 2004 Games in Athens.

"If we hadn't had a Leander in those days, then it would have been harder," added Tanner.

"It wasn't the only thing going on, it wasn't that we didn't have good people doing things, we did. But they were in clubs and we didn't have a centralised programme."

Tanner introduced rowing's World Class Start programme in 2002, a talent identification and development scheme which produced five of Team GB's 10 Olympic champions in London 2012 as well as Thornley, Leander's current captain and Olympic silver medallist.

The Redgrave-Pinsent Rowing Lake was also opened in 2006 at Caversham, Berkshire, to house the elite training centre for Team GB squads, of which two thirds of Leander's 60 rowers are part of.

Tanner says the club had an "attitude" to "bring people up to the GB level".

"That is their DNA. Whoever goes into that club, whether its a youngster or whatever, they would be looking to see them rowing for GB one day," he added. "It does a very good job indeed."

The challenge for Leander now is that it is "almost too successful", adds Tanner, "in the sense that the Team GB rowing team does take its athletes, therefore they have to be constantly finding new ones".

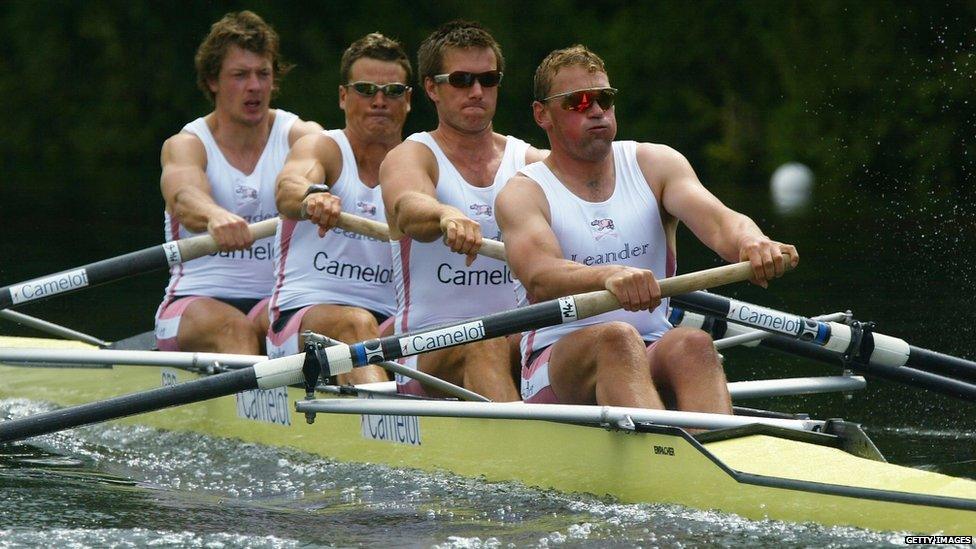

Steve Williams, James Cracknell, Ed Coode and Matthew Pinsent rowing for Leander Club in 2004 at Henley Royal Regatta

To help achieve that, the club aims to break down barriers faced by young rowers, such as funding and accommodation, to allow them to focus solely on the sport.

But it is the culture of Leander Club, rather than money, which breeds enduring success.

As you enter the clubhouse an honours board shows off Leander's medals, but also emphasises its high standards by engraving winners in gold, and any other medal in black.

It tell stories of success and triumph by Leander athletes who have competed in the Henley Regatta, World Championships and Olympic finals, stretching back to Henley winners in 1840 and the club's first Olympic medal in 1908.

The landscape itself hasn't changed, with old photographs showing the river is still the same today.

"There's a sort of sense of belonging, a sense of history," added Pinsent.

The Leander honours boards only display gold medal winners in gold, anything else is in black

"You look at these old pictures and some of the times these guys are doing back in the day, and even the times we were doing 20, 30 years ago, it has moved on and that is undeniably the challenge that keeps the club alive."

Since being granted membership, many women have gone onto international success, including current captain Thornley, who is the only the second woman to hold the position.

The 30-year-old, who is unable to defend her single sculls title at the forthcoming European Championships, won an Olympic silver medal alongside Dame Katherine Grainger in the women's double scull at Rio 2016 and said Leander "seemed the obvious choice" as a place to row.

"If you are wanting to follow in the footsteps of the best people, then that's where you want to go", she said. "Nothing (at Leander) is holding you back from being able to train and perform to the best level."

Dame Katherine Grainger and Leander captain Vicky Thornley at Rio 2016

As for its president, Randall says opening Leander up and encouraging people to join no matter where they had rowed beforehand "made a big difference".

"What makes it special for me is its ability to change," he said. "We have to keep changing to accommodate the very latest developments in rowing, the social changes, the financial changes, the business model. We just have to keep adapting. What we can't do is stand still, otherwise we will be overtaken.

"We have been the best rowing club in the world for a long, long time, but it takes an awful lot of work to keep it there."