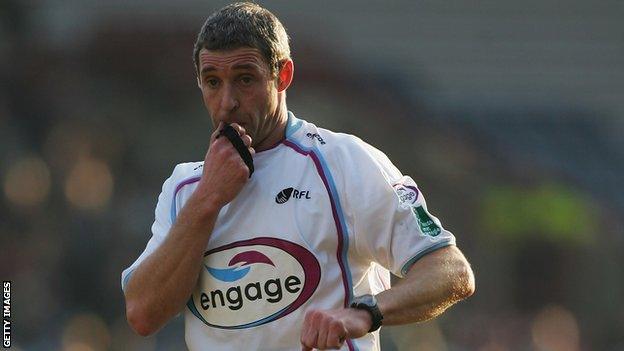

Ian Smith: Former referee says he often felt 'lonely and isolated' during matches

- Published

Rugby league tackles mental health issues

Former Super League referee Ian Smith says he often felt "lonely and isolated" when he took charge of big matches.

And he admits to hitting rock bottom after leaving the game, saying the constant criticism of the man in the middle can have a lasting effect on mental health.

"The external pressures that referees and match officials are put under, from all stakeholders - from owners, to players to coaches, to fans - I think what people don't understand is that inside that uniform there is a human being that does make mistakes," Smith told the BBC 5 Live Rugby League podcast.

"They think it's unacceptable for a match official to make mistakes. That pressure that's placed on them can have a mental health impact."

Smith, 51, says he had real problems when he left the Rugby Football League 18 months after a career that included 12 years as a top-flight referee.

And he adds it took him eight to 10 months to turn his world around, with the assistance of the game's mental-health charity State of Mind., external

"When I left the RFL, I suffered some mental issues. I really started to struggle. I felt I'd lost my identity," he says.

"I'd refereed in Super League for 12 years and when you are under that type of intense pressure both on and off the field to perform, it effected my mood swings during and after the game and through to the next appointment.

"But, when you're actually performing at a professional level, you just get on with it because you have got the next match to come.

"It's incredibly lonely. You speak to players and they have the comfort of their team-mates. And, even though we have touch-judges and the match officials' department, when you are out there it is still a very lonely and isolating place.

"At times you can feel incredibly lonely."

Ian Smith refereed in Super League from 1999 to 2010

'We're making a difference'

Smith is now using his experience to help others tackle their mental health issues.

He has become a presenter with Offload - an offshoot of State of Mind, which was set up by mental health experts and ex-players after popular Great Britain international Terry Newton took his own life seven years ago.

"It gets like-minded men to offload their mental health issues in a safe, secure and non-judgemental environment," says Smith. "It's absolutely fantastic.

"Some of the tweets we get back are amazing. People have said we're making a massive difference and they had contemplated taking their own lives before they got on this programme.

"It's incredibly rewarding."

The whole game united in support of State of Mind this weekend, with the entire round of Super League matches dedicated to its mental health message. Players wore T-shirts bearing its slogans during warm-ups, and the charity's representatives set up information posts outside each ground.

'I couldn't get the thought of suicide out of my mind'

Danny Sculthorpe is one of the former players involved with State of Mind. He contemplated suicide when he left Bradford after a training injury left him unable to play.

It led to him losing his house and being unable to support his wife and two young kids.

"I couldn't get the thought of suicide out of my mind," he says.

"I did the typical bloke thing for months and months - I didn't tell anyone. I thought it was a sign of weakness. But what I have come to learn is that if you can talk about your problems and admit you're struggling, you're more of a man than if you keep it to yourself."

Sculthorpe, 37, is one of the main State of Mind presenters.

"The RFL got me loads of help - they got me talking to a counsellor," he says. "It sounds too good to be true, but talking beat the medication. Medication worked for me, but it was talking that saved my life."

State of Mind began its work at rugby league clubs, but now delivers presentations throughout the country, to what Sculthorpe describes as typical alpha-male groups.

"It's amazing, unbelievable," he says. "As soon as you go in and mention mental health, people switch off. But the reality is everyone has mental health, just as they have physical health.

"When we start telling our stories, they are getting it. If a rugby league player can speak about how they're feeling then anyone can.

"We did a construction site 12 months ago, down in London. The day after, seven blokes went in to HR and said they were struggling and needed to get help.

"On construction sites you're five times more likely to die from suicide than an accident on site."

Danny Sculthorpe (right) played for Wigan Warriors from 2001 to 2006

'I think this is a world first'

State of Mind has also targeted schools. One recent presentation led to a teenage boy opening up about his depression and getting treatment through counselling.

"We went back to speak to the teachers a month later. A week before, the parent of the young lad went in to say thank you for getting State of Mind in because she had got her son back," said Sculthorpe.

One of the charity's co-founders - mental health nurse Malcolm Rae - says its success is mainly down to using the experiences of the players, but that carefully chosen language helps breaks down barriers.

"One of the barriers to blokes seeking help is stigma," he says.

"So we particularly used language like 'help a mate' or 'feel good, play better'. And we use phrases like mental fitness instead of mental illness. Language is so important in engaging with people."

Rae believes State of Mind could now be replicated in other sports.

"I think this is a world first," he says. "The rugby league community and the RFL deserve every credit for enabling this to happen.

"The Department of Health's recent revised policy on suicide prevention, and the Parliamentary Select Committee both commended rugby league and State of Mind and feel we are the benchmark for other sports."

Former referee Smith says working with the charity is helping his continued recovery.

"I'm in a great place at the moment," he says.

"Every time I present for State of Mind or Offload, it's like my own therapy class. You're picking up little ways of coping and moving forward."