Siya Kolisi and South Africa's triumph 'a story to inspire far beyond the rugby pitch'

- Published

Watch key moments from South Africa's emphatic win over England

Sometimes a storm comes in and all you can do is yield in its path.

Heavy metal thunder on the pitch, the echoes of history off it. This was a South Africa World Cup win that began with a stumble seven weeks ago and ended with a noise that will roll across the oceans from Yokohama to the cities and townships of a very different continent.

England came looking for a fresh peak and never got within striking distance of the summit. The Springboks arrived with a rich past and will leave with new heroes and maybe a greater prize still.

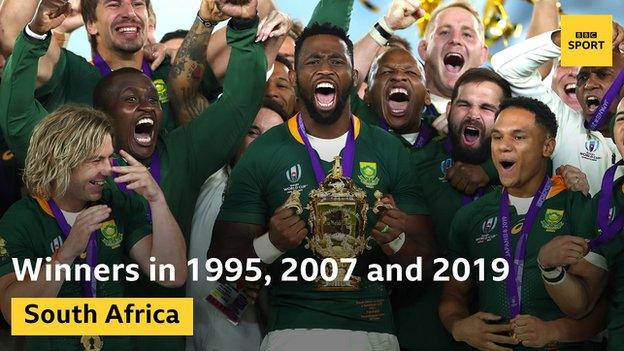

There have been totemic South African captains before and there have been two who have also won the World Cup. But as Siya Kolisi, the first black skipper in the country's history, lifted the Webb Ellis trophy into the clear evening sky, golden ticker-tape streaming down behind him, if felt like something changing forever.

When Nelson Mandela celebrated with Francois Pienaar at Ellis Park in Johannesburg in 1995 there was one black player in the Springbok team. When John Smit did the same, arm in arm with Thabo Mbeki in Paris in 2007, there were two.

This was a moment and an image that more truly represents the balance and nuances of the complicated nation behind it than even those iconic triumphs in its wake. In the team's leader is a story to inspire far beyond a rugby pitch and podium.

Springbok captain Siya Kolisi - and his daughter - salute the crowd after winning South Africa's third World Cup trophy

A kid from the townships who was born with nothing, whose parents were too young and too poor to raise him and so entrusted him to his grandmother. A rugby obsessive who played without kit, whose mother died when he was 15 and whose grandmother died in his arms a few months later.

The pressure of World Cup finals can do strange things to hardened players. England walked out on Saturday night confident and relaxed and left it bemused and broken.

The Springboks felt it too but maybe they felt something else on top. You watched how Kolisi and his team-mates went at this game and there was an energy and relentlessness that comes from a deep source.

"In South Africa pressure is not having a job," said coach Rassie Erasmus afterwards. "It is one of your friends being murdered.

"Rugby shouldn't be something that creates pressure on you. Rugby brings hope.

"We've got the privilege to bring people hope. Hope is when you play well and people watch you on Saturday, have a nice barbecue and watch the game and feel good after.

"No matter your political views, for those 80 minutes you agree. That's not our responsibility, that's our privilege. The moment you see that, it becomes a hell of a privilege."

"Amazing!": South Africa rugby fans go wild at World Cup win

It was Erasmus who made Kolisi his captain and Erasmus who took over a team, 618 days ago, that was unsure of its rugby identity as well as its cultural weight.

He brought back some of the old traditions and married them with a new outlook: we will be rooted in the past but we will look to the future. Experienced stars recalled from overseas, younger players given not just the chance to play but the chance to grow.

At the heart of this utterly comprehensive win were timeless fundamentals of the game. If your scrum is going backwards you need miracles to win games. All sides make errors but if you compound them you will struggle to escape. Slow ball means stultified attack.

England were battered. It went wrong within 30 seconds when they conceded their first breakdown penalty and it continued to go wrong at pace even as you waited for them to do the simple things to put it right.

Joe Marler and Billy Vunipola look on as South Africa celebrate their crushing victory in Yokohama

Kyle Sinckler gone with concussion before three minutes were up. Wild passes thrown behind runners. Restarts knocked on, kicks sent straight to touch.

All the time the scrum kept splintering and referee Jerome Garces kept blowing his whistle. A strange collective panic, an absence of alternative strategies even as the original one was exposed as flawed.

"I don't know why we didn't play well today," said a shell-shocked Eddie Jones in the aftermath.

"You can have the most investigative debrief of your game and you still don't know. It just happens sometimes. We'll be kicking stones for four years. And it's hard to kick stones for four years."

Only twice did England threaten, once when they hammered away at the Springbok line at 6-3 down only to come away with just a penalty, and again briefly in the second half when Owen Farrell had a long-range penalty to bring it back to 15-12.

In truth they never came close. The week before against the All Blacks five or six players had produced their finest displays in a white jersey. In a game that mattered more there were the same number or more who dropped significantly below where they had been all tournament, and it is there that the regret will linger.

Cheslin Kolbe's try sealed a 32-12 win for the Springboks as they made it three wins from three World Cup finals

When South Africa beat the same opponents in the final of 2007 it felt like the victory for England was even reaching the last two. Here England promised so much more.

There were nine survivors in the starting XV on Saturday who had been part of the disastrous World Cup campaign four years ago, when they failed to even escape the group stages. Now the knock-out stages have delivered a blow that is arguably crueller still.

When the final whistle went England players were strewn all over the Yokohama turf. It was a poignant image but it could only be a sub-plot to what else you could see all around.

Pienaar dancing in the crowd, current South African president Cyril Ramaphosa in his own dark green Springbok jersey. Smit grinning pitch-side.

Kolisi 'grateful' for South Africa unity

And on a large flat podium in the centre of the field, Kolisi - hoisting the graceful little gold trophy, mouthing silent incantations into the darkness above.

"All I want to do is to inspire my kids and every other kid in South Africa," he would say later, pot still by his side.

"I never dreamed of a day like this at all. When I was a kid all I was thinking about was getting my next meal.

"A lot of us in South Africa just need an opportunity. There are so many untold stories. I'm hoping that we have just given people a bit of hope to pull together as a country to make it better."