Willie John McBride at 80 - Lions, Attenborough and apartheid

- Published

'Nothing was more important than wearing the Irish jersey' - Lion king McBride at 80

The great man emerges into the evening sun, casting a shadow as imposing as the grand tree which occupies centre stage in his Ballyclare garden.

Where once there was an abundant weave of chestnut brown hair, there is now a rich silver thatch, the mane shows no sign of diminishing and neither does his frame.

Eyes darting, tongue wagging and jawline jutting like a rock face promontory.

Even now at 80, Willie John McBride has such presence, he is so strikingly statuesque that he might have been quarried fully formed and perfectly proportioned from the Antrim plateau.

As it was, the man voted world rugby's personality of the twentieth century was quick to remind me he was "made in Moneyglass".

"I suppose the genes were kind to me, but my physique was forged on the farm," says McBride.

"My father died when I was just four or five and my mother was an exceptional woman. I loved those early formative years but they were challenging.

"Each Halloween I reflect on his untimely passing. He never got to see me play but I often wonder what he would have made of it all.

"It really makes me, especially at my age, appreciate the privilege of being a parent and grandparent."

Rugby's Attenborough

Ireland captain and coach, the most-capped British and Irish Lion of all time and veteran of five Test tours across two decades. The footballer has long since gone, however the farmer remains.

McBride keeps chickens and donkeys. His garden is a compact field which folds into a copsed hillside, so lush and verdant it could have its own microclimate. It doesn't, but it does have its own menagerie.

There nestled in the crook of a garden incline, chickens chattering and donkeys braying, the old lion king pulls up a seat, preparing to ruck and maul in a kit bag of memories.

The mind remains as agile as a darting Gareth Edwards, the senses as furtive as those of a forest deer, the treacle thick voice as sonorous as Stentor. From his summer seat it booms across time and continents echoing all the way to the far off Transvaal.

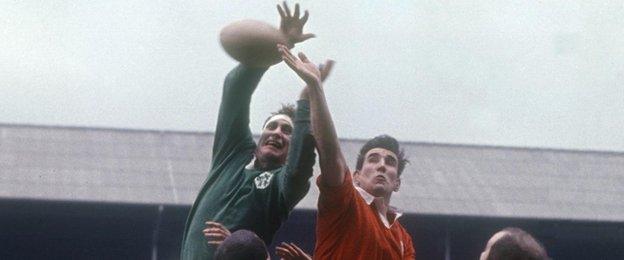

McBride won 63 caps for Ireland from 1962-75

"For all the memories that rugby has given me, perhaps the most enduring was off the field," McBride says as his eyes widen and well.

"I'll never forget standing on the banks of the Mara river in Tanzania and marvelling at the migrating wildebeest, hooves thundering down banks and crocodiles snapping at them in a frenzy."

"That could be a metaphor for your sporting life," I quip, which draws a chuckle.

"I do love wildlife. It would have been easier on the body had I followed in David Attenborough's footsteps," he responds.

There was a time when he was as busy globetrotting as Attenborough.

In 1974, amid a welter of controversy, Willie John led the Lions on a tour of South Africa.

Back then, apartheid South Africa was under a blanket boycott by many of international sports' governing bodies, including Fifa and the International Olympic Committee.

However rugby rolled on and the McBride-led 'invincibles' went the full tour unbeaten.

McBride leads out the Lions on the controversial 1974 Tour

They had travelled in defiance of the then British prime minister Harold Wilson. To some it was a high watermark, to others an indelible stain on an illustrious career.

I ask: "Now at 80, do you have any regrets about flouting the boycott and touring South Africa?"

I sense the question has momentarily wrong footed him, and after a brief pause he responds with: "No, I'd change nothing."

"The squad was under pressure from the media and some protestors before we left London," he added.

"We had a meeting and I said we were rugby players not politicians, but if anyone wanted to leave then they could go home.

"No one left. It was my belief then, and still is now, that sport should be kept separate from politics."

I owe everything to Penny

The shadow of apartheid eclipsed another personal footnote. That same year, he had captained Ireland to victory in the Five Nations.

The following was his last in a green shirt, and fittingly his first and only try for Ireland came in his final game at Lansdowne Road against France.

Would his career have been incomplete had he not scored an international try?

"Ah, not really but I enjoyed the moment," McBride responds.

"Some young fella jumped the hoarding and wrapped me in a tricolour, and forty years on I met him in an airport.

"'Thanks for the memories', he said, having explained who he was," recalls McBride.

"I smiled back and said: "That's what it's all about...but you'll still be hearing from my lawyer."

McBride chats to Gordon D'Arcy, Denis Leamy and Rob Kearney after Ireland's 2009 Six Nations Grand Slam.

In a glittering career, is there one rugby memory which prevails above all others?

"Beating the All Blacks in their own back yard in 1971 would have to be up there. We are the only Lions team in the history of rugby to go to New Zealand and win the test series outright.

"We had so many talented rugby footballers, Mike Gibson was a genius and Gareth Edwards was, for me, the most naturally-gifted footballer I've ever played with or against."

The sun is setting and Willie John is lost in the mists of time - back in Eden Park, rampaging through a phalanx of All Blacks, only this time, over his shoulder, appears his wife, Penny, to whisper: "It's getting a little cold out here".

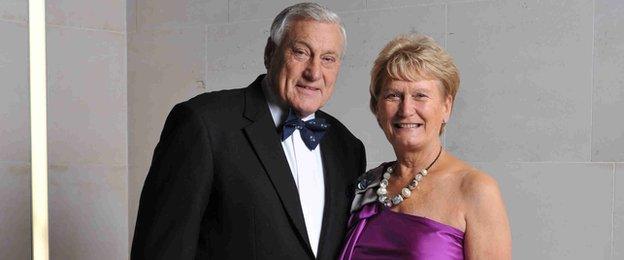

"We've been married 53 years," the great man continues.

"Some of those tours were five months long and I owe everything to my wife.

"Rugby even gave me Penny. I met her on a blind date, her dad was the Ireland team doctor."

Willie John and his wife, Penny

If never taking a backwards step was the key to rugby success, what, I wonder, has been the secret of over half a century of marriage?

"Oh, that's simple," he shrugs.

"I always remind her it's a long walk from Ballyclare back to Malahide."

The tongue in cheek observation is book-ended with a worldly wink.

'I want to live forever'

It's nice to be remembered again - Willie John McBride

It's easy to forget that Willie John is now an octogenarian, but as it was on the field, so it is off it - he remains master of all he surveys, composed and in control.

As he ambles to the door he pauses before entering and offloads one last pearl.

"Eighty, I don't feel it. I said to my doctor the other day, 'we have a problem'."

"What's the problem?", the doctor responds.

"I want to live forever, I said."

"And what's the problem with that, Willie?"

"Well, the problem is doctor, you're the key to ensuring that...."

The guffawing is contagious and so is the man.

"You'll be back for my 90th?", McBride asks as we go our separate ways.

"I will Willie, I will. Sure you bring a ball and I'll bring a bottle."

And, with that, off into the twilight we traipse.