Alix Popham: Ex-Wales flanker on early onset dementia diagnosis

- Published

I don't want to be a burden on my family - Popham

"I don't want to be a burden on anybody. That's the thing that plays on my mind."

At just 40 years old, Alix Popham was diagnosed with early onset dementia. A former Wales flanker, he is a husband and father of three girls, trying to navigate an illness that affects his personality.

"I felt like there was a rage inside me boiling up and I just needed to get it out," Popham told BBC Sport.

"I slammed the doors and broke them. The bannister in the house, I pulled that off. After that aggression has come out, I'm thinking to myself, why did I do that? I have no control over those actions at that time."

Popham would forget people's names, or lose track of a conversation. His wife, Mel, remembers him setting the kitchen on fire. "He put the grill on and closed it. Darcy [their 2-year-old] was in her high chair. I could smell burning," she says. "It was pretty frightening."

But it was something as normal as a bike ride, following a loop Popham had taken hundreds of times, that was the turning point.

"I got lost on the bike ride and had a blackout moment," Popham, now 41, says.

"He said he'd got lost, but he just got to a point where he didn't know which way to go," Mel explains. "He had to retrace his route on an app. He came home and sort of broke down to me."

Popham went to his GP and underwent tests. They showed his short term memory was, in his words, "really bad". In the winter of 2019, Popham was approached by a neurologist who specialises in head injuries. By then, things were getting worse.

"If it is two people talking, there are no problems," he says. "But if there are lots of people talking or background noises, I couldn't take in the information. I'd come out of meetings thinking what was that all about?"

Mel also spoke to the neurologist. "She told him things like me mixing up words, forgetting words, losing my train of thought in conversations where I'd be telling a story about something that happened recently."

On 16 April, Popham was diagnosed with early onset dementia. His diagnosis pushed him to become one of eight former rugby union players who are in the process of starting a claim against the game's authorities for negligence.

Mel, who was physically sick after seeing the damage to her husband's brain, struggled to grasp what was happening.

"Every time I looked at Darcy I burst into tears," says Mel. "I kept thinking, how can this be happening?

"We made a decision not to have another baby, which we were planning to do this summer. That was really tough, but we felt knowing what we know, that wasn't the right thing to do."

'Watching the lights fading gradually in him'

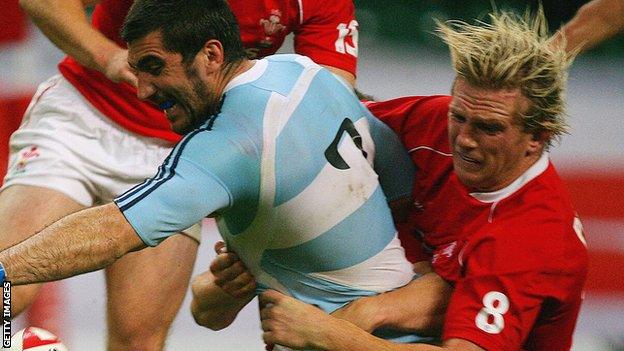

Alix Popham (right) had a 14-year professional career

Popham describes the effects of concussions and sub-concussions on his brain as a leaking tap. "If it drips once or twice there will be no mark on the floor, but if it dripped for 14 years, there would be a big hole," he says. "That is the damage that is showing on the scans."

The diagnosis has led him to contemplate his future. He knows, for example, that he may not be able to walk his daughters down the aisle.

"The neurologist has given us a five to 10 year management plan, but how quickly the symptoms get worse after that, nobody knows. That's the scary bit for me" he says.

"You end up talking about adapting the house, carers coming in, and as a 40-year-old, to hear that, was upsetting.

"It's watching the lights fading gradually in him," explains Mel. "My biggest fear is Alix ending up in a nursing home. And for my daughter, my biggest fear is her losing her dad; him being here but not being the same Alix.

"We had so many big plans for the future. We've got different plans now."

Popham, known for his block-busting tackles, is in no doubt that the concussion protocols when he was playing were not adequate.

"You thought concussion was when you were out cold on the pitch," he says. "If you felt a bit groggy, you would have a sniff of salts. You didn't want to come off the field as a player and show weakness.

"You knew your body was going to be sore in retirement, but nobody knew your brain was going to be in bits as well."

From being a youngster, Popham was told that if he went into a tackle at anything less than 100%, he would be injured. So he gave it his all three times a week in UK training, then four times a week in France, followed by a game on Saturday. For 14 years, that was his routine. His doctor believes he had more than 100,000 sub-concussions in his career.

"I haven't got memories of large chunks of my career," he says."During lockdown they repeated the 2008 game against England, when we won at Twickenham. I have no recollection of being on that pitch.

"We played in South Africa and I met Nelson Mandela before the game. I've got the picture on the wall, but I can't remember meeting him."

The Popham family want to raise awareness of the impact rugby head injuries can have. Mel estimates they have been contacted by a hundred of Popham's former team-mates and friends who are experiencing similar symptoms. It has helped her, too, creating a community of wives and partners that she can talk with.

Their home life has changed. "We don't ever shout to dad from another room like we used to," Mel says. "We always make sure we are in front of him when we speak because we have realised the part of Alix's brain that is affected is distinguishing noises from each other.

"We try to take something positive from every day so that no bad day is an all bad day."

They hope that by sharing their story, they can raise awareness of the illness, and encourage people to come forward. Both love rugby and want it to be as safe and as informed as it can be. But their lives have changed.

"Sometimes there is a look in his eyes of him not getting or understanding something," Mel adds. "That was never there before. It is really hard to witness."

More information about dementia and details of organisations that can help can be found here.