Kyle Steyn: From growing up with Nelson Mandela to facing South Africa for Scotland

- Published

Steyn scored four tries against Tonga on his second appearance for Scotland

Autumn internationals: Scotland v South Africa |

|---|

Venue: Murrayfield, Edinburgh Date: Saturday, 13 November Kick-off: 13:00 GMT |

Coverage: Follow live text commentary on the BBC Sport website & app |

As Kyle Steyn was running in his four tries against Tonga a fortnight ago, we could see the smile on his face but we didn't really know much about the story behind it.

When he punched the air in victory against the Wallabies on Sunday, we could see a deliriously happy player but sometimes what we don't see is the most interesting thing, the thing that tells you everything.

Had we been in the physio room with him for close to 14 months, we'd have had more of an idea of what Tonga and Australia meant to him. Had we seen the state of him when he tore his hamstring off the bone in 2020, and when he did it again just when he thought he was getting places after long months in the margins, then we'd have had the full picture.

We see the glamour. We don't see the grind.

"I had a mountain to climb," he says. "At times I looked up and I thought, 'that's a very large mountain up there'. It was a dark time. I just felt like a gym rat doing rehab day after day. I wasn't a rugby player any more, so what was I?

"A lot of good people helped me along the way - team-mates, the staff at Glasgow, my fiancée, my family at home in South Africa. I was lucky I had so many people who had my back."

Guarding 'Tata' after spying for apartheid state

This is a story of a player from Johannesburg with a Scottish mum and Scottish grandparents. But it's also a father and son story.

As heartwarming as Steyn's tale is - and it might get even more fantastic if he's part of a Scotland victory against his native South Africa on Saturday - it'll forever struggle to match the epic yarn of his dad, Rory, who'll be in the stand at Murrayfield.

Where to start? "I was born in 1963 and apartheid was all I knew," begins Rory. "I thought it was normal, I thought that's just how life is. All my boys - Kyle, Iain and Craig - were born post-apartheid so they're Born Frees, as we call them, but when I went to school every face was lilywhite. There was no integration.

"I became a cop on the beat until one day special branch came recruiting. They put me into a section called the Churches section because the South African Council of Churches was used as a conduit to funnel money into the country to support anti-apartheid activism.

"My job was to get those old reel-to-reel tapes and make notes of any subversive conversations. The activists were pretty good at disguising what was going on. They knew that the tentacles of the apartheid state spread wide."

In 1990, that system was dismantled, the ban on the African National Council was lifted, and the order was given for Nelson Mandela to be released from prison after 27 years of incarceration.

Rory Steyn was a lieutenant, then a lieutenant colonel. He was put in charge of VIP protection. When Mandela became president of South Africa in 1994, Steyn became his head of security.

There was a meeting of high-ranking officials to discuss his early life as an officer in the old regime but Mandela intervened. Subsequently, the president told him: 'You know they wanted me to fire you because you're white.'

The president not only left him in charge, but brought him closer. He was with Mandela from his first day in office to his last.

"We called him Tata," explains Rory. "Us whities learned from our African colleagues that in their culture Tata means father and it's a respect thing. They revere their elders and Tata was an acknowledgement of his wisdom. I brought my boys to see him. Kyle would have met him numerous times."

Meeting Mandela with an All Blacks cap on

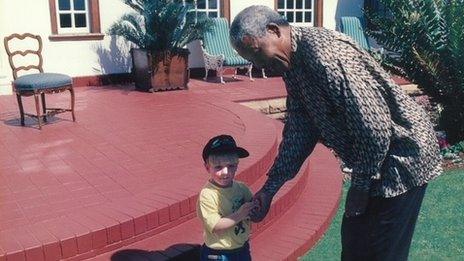

A very young Kyle Steyn meets Nelson Mandela in September 1996 at his official residence

The first time Kyle met the great man was 1996. "Yeah, I was only a toddler," he recalls. "Can you believe this, dad brought me to see President Mandela and he put an All Blacks hat on my head. I mean, what were you thinking, dad?

"Mandela was full of warmth and kindness. That's what I remember. You arrive at his residence and it's a pretty intimidating environment but he was very relaxed. He must have been incredibly busy but he made you feel like he had all the time in the world for you."

It's weird how life goes. When Rory was listening to those phone taps as a young special branch officer, he was detailed to focus on one woman in particular: Mary Mxadana, PA to the general secretary of the Council of Churches.

When he became the team leader of Mandela's protection unit, he went to the union building one day to get his programme of engagements for the following week and there was the same Mary whose phone he'd listened to years before. She was now the president's principal PA.

"I said, 'I need to tell you something, I was a special branch cop and we bugged your phone and I used to listen to your calls'," says Rory. "She threw back her head and roared with laughter. What a fantastic woman."

He travelled the world with Mandela. In 1997, they were in Edinburgh and the Queen invited the president for tea at the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

"Ordinarily, we'd just drop him at the door and in he'd go, but I was told to go with him because he was in his 80s and they were worried about the stairs. We were in a room and the Queen walked in and with these two ears I heard them call each other by their first name.

"He said, 'Your majesty, how are you, Elizabeth?' and her majesty said, 'My president, how are you, Nelson?' It was such a special thing to witness."

When Mandela passed away, Steyn and his old colleagues in the protection team were invited to say their own goodbyes. There were 10 of them, five either side of the coffin at the air force base in Pretoria, just before the president made his final journey.

"Being with him for five years was one of the greatest privileges of my life and being there at the end one of the greatest honours," he says.

Shady syndicates & Cronje's confession

There's another layer to Rory's story. During the Rugby World Cup in South Africa in 1995, he worked security for the All Blacks - this is where Kyle's New Zealand cap came from.

For more than 20 years, he's said he believes that the All Blacks were deliberately poisoned before the final against the Boks.

"I can only testify to what I saw with my own eyes and from the Thursday before the Saturday final, that hotel was like a scene out of Saving Private Ryan," he says. "There were sick players everywhere. I heard that a very powerful sports syndicate out of Singapore were involved but we'll never know for sure.

"It's come up a lot over the years. Kyle was playing his rugby with Griquas in Kimberley, which is a very conservative Afrikaans town. His team-mates said, 'What's your dad doing? Why is he raising this stuff now?'

"It was made out that I was trying to detract from the victory, but I wasn't. I'm not saying that South African rugby did it. I remember Kyle asking me to stop talking about it."

When the late Hansie Cronje, once the darling of South African cricket, confessed to match fixing, it was to Rory Steyn he confessed. It was at 2.30am in a hotel in Durban while Steyn was looking after the visiting Australia team.

The South Africans, Cronje included, were staying in the same hotel. "I knew Hansie and he phoned me," he says. "I went to his room and he was basically asking me to arrest him. He'd had enough of living a lie. It was very, very sad."

Green-blooded Scotland supporters

Rory was there when his son made his Scotland debut against France in 2020 - and the whole family were watching from Johannesburg when he got those tries against Tonga and when he came off the bench against Australia.

"Kyle never wanted to do anything else other than to play rugby," he explains. "We could never buy him a toy for Christmas or for his birthday. If it wasn't a ball, he wouldn't play with it.

"My wife's dad was a very proud Scot and I said to him one day when Kyle was playing, 'You know Pa, if he takes this forward, he might play for Scotland and he said, 'Och, no, he doesn't want to play for Scotland'.

"They weren't very good at the time. They are now. One of the great regrets my wife and I have is he never saw his grandson play at Murrayfield. My own dad didn't see him either. It would have been a source of tremendous pride for them.

"For the family, it's an unmitigated pleasure to watch him. My blood is green, but you always support your son. We're all Scotland fans now."