Doddie Weir: Obituary for iconic Scotland and British and Irish Lions lock

- Published

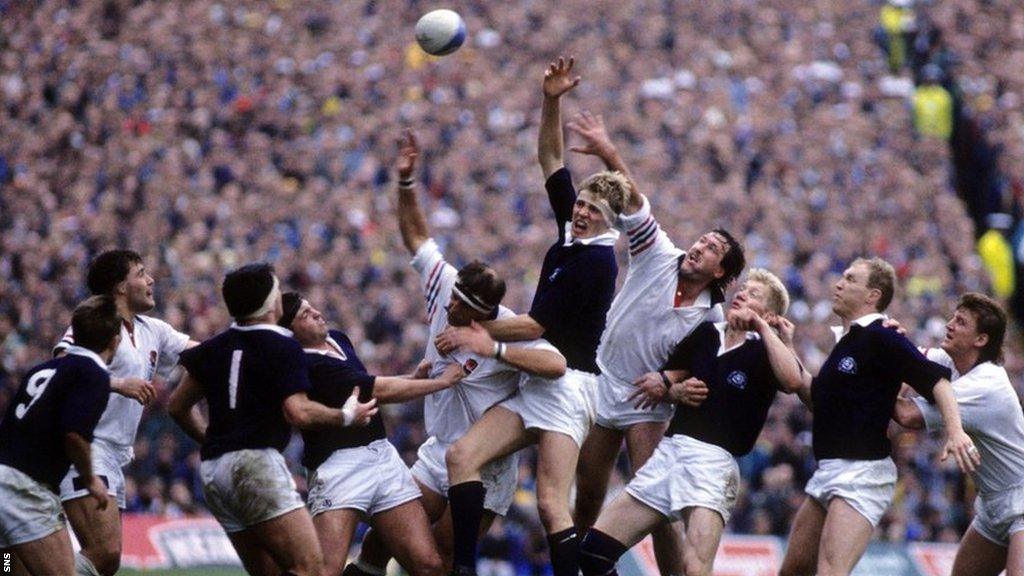

Doddie Weir (centre) challenges for a line-out in the 1991 World Cup semi-final against England

The images of Doddie Weir's playing years have a glorious consistency; he is soaring at a line-out or carrying the ball like a mad giraffe, as Bill McLaren once described him. He is a towering, smiling giant. Mischievous, charismatic, funny.

All of those freeze-frames and all of that video tell us what a presence he was on the rugby field.

From Melrose, where he won a league title as a young man, to Newcastle Falcons where he won another. To Scotland for a decade and the Lions in South Africa - his tour cut short by a horrible act of foul play by a local hatchet man - and back to the Borders, where it started and where it finished.

For every minute he was 6ft 7in of joyous chaos.

There's a reluctance in spaces like this to refer to sports people by their first name or their nickname - he was christened George - because you don't want to appear overly familiar, but there are exceptions.

Even people who didn't know him felt like they did. Even those who were never in his company automatically referred to him as Doddie and considered him a mate.

Some folk just have it, whatever 'it' is. And Doddie was one of those. He brought out the best in people. He saw it as a personal mission to make you smile and leave his company feeling better about yourself.

There's a picture of a 20-year-old Doddie celebrating that league title with Melrose when league titles really, really mattered in Scottish rugby. It was 1990 and Jim Telfer was the coach. Telfer always said the triumph with Melrose meant more to him than the Grand Slam with Scotland that followed a week later, a victory he helped create as Ian McGeechan's assistant.

The life and career of Scottish rugby legend Doddie Weir

That photograph is of Doddie with his Melrose team-mates, a smile as wide as the Tweed on his face. He was in his element. His 10-year and 61-cap international career was just beginning and it was split between the amateur and professional eras, but there's no doubt which one he preferred.

He was a social animal, not a gym monkey. He loved talking rather than training. Lift a pint or lift a weight? There was no decision to be made.

He once said that no bleep test - or any such device to monitor the fitness of the first wave of professional players - could judge a guy's personality when the chips were down on the pitch and when his mates needed him to go the extra mile. There was no machine to measure character. He was one of the great ones.

His views on rugby were that it was a vehicle for making friends and memories. He wanted to win, of course. No prouder Scotsman has worn the jersey or paraded the tartan with such gusto, but most of all he wanted to have a laugh. And that's what he did.

'His relentless energy was awe-inspiring'

As big a figure as he was, his aura was never greater than when he had to use a wheelchair because of the effects of motor neurone disease (MND). He was never stronger than when his body was breaking down, never more commanding of worldwide respect than when he'd lost the ability to speak and could only communicate via a voice app operated with his eyes darting around a screen of letters.

His relentless energy in fighting an illness without cure was awe-inspiring. He said the only drug available to him was positivity - and he gorged merrily on it. The many millions of pounds he raised for research through his My Name'5 Doddie Foundation, the money donated to families who were suffering as his family were suffering, the lives he made better along the way. His legacy could circumnavigate the rugby world many times over.

In December 2016, he was given the diagnosis and was told he'd probably be unable to walk within a year. He beat that prediction for a start. Medical experts say that, on average, a third of MND sufferers die within a year. He saw that one off, too. More than 50% of people pass away within two years of diagnosis.

Three years after his diagnosis Doddie was still bringing the weight of personality and his wonderfully dark humour to the table. "The only people who I think are upset about being three years in are my trustees [of his Foundation]," he joked. "They thought they were only signing up for six months."

His attitude was rooted in grim realism. This thing had befallen him and he had better "crack on" as he put it. "I have never, ever thought 'Why me?' It was, 'Right, let's get this sorted… it's like with rugby. If you don't get in the team, do you give up your jersey or do you fight?"

Scotland captain Jamie Ritchie greets Doddie Weir before the November meeting with New Zealand

After being the star turn at a plush charity gala - there were many in his honour and many awards, too - he said: "In a bizarre way I'm living the dream because I'm having a living wake." People laughed and maybe some shed a tear at such indomitable bravery.

He was still doing interviews five years after getting the news, posing on his mobility scooter on his farm near Galashiels like he was on a Harley Davidson ready to roar off into the world. "I'm still living and still smiling," he said.

And still campaigning. He was critical of government for, as he saw it, failing to deliver on promises made about the funding of MND research. He was questioning about medical experts not moving fast enough in trialling new drugs.

His movement was compromised but never his mind or his passion. Other people with MND, with none of his profile or influence, must have seen him as their champion, fighting the good fight in pursuit of something that stops this disease being a death sentence.

Princess Anne presents Doddie Weir with the Helen Rollason Award

He did it with wisdom and humour while knowing his life was ending, while knowing that his time with his wife, Kathy, and their three boys, Hamish, Angus and Ben, was running out.

When his sons wheeled him to the side of the Murrayfield pitch before the All Blacks game earlier this month, the atmosphere inside the stadium was an extraordinary amalgam of happiness and sadness - and wonder. More than six years had passed since the diagnosis.

He'd won 33 of his 61 caps at Murrayfield. He'd made his debut there, scored his first international try there, played a World Cup semi-final there.

Many would argue that his most memorable appearance of all was that last one, in the chair with his sons by his side, two sets of players applauding him and the love of 67,000 beaming down like sunshine.

Nobody could imagine the effort it must have taken for him to be there, but then not many of us ever encountered a character like him before. Gone, yes. Missed, profoundly. Forgotten, never.