Blood brothers - bonds and betrayal on a rugby pitch

- Published

Tom Williams, kneeling on one knee, runs his hand over the blades of grass. His eyes are desperately scanning as his heartbeat rises further.

It is deep in the second half of the 2009 Heineken Cup quarter-final at the Stoop. Williams' team - Harlequins - are a point down.

It is the biggest match the 25-year-old has ever played in.

Harlequins are aiming to make the last four for the first time. Trying to stop them are a star-studded Leinster team featuring the likes of Brian O'Driscoll, Jamie Heaslip, Rob Kearney and Felipe Contepomi.

The stakes are sky-high and time is tight.

But Williams has a more pressing concern.

"I had taken the blood capsule out of my sock, put it in my mouth, and then tried to chew down on it," he remembers on Sport’s Strangest Crimes: Bloodgate, a BBC Radio 5 Live podcast that delves deeper than ever into one of rugby's most infamous scandals.

"But it fell out on to the floor. I'm red-green colour-blind. I can't see the thing on the floor so I am searching around for it.

"It's just the ridiculousness of it."

A few minutes later, everyone could see it.

Williams, having found the capsule and burst it between his teeth, was led off the pitch, with strangely scarlet blood streaming from his mouth, splattering on Quins' famous quartered shirt.

A blood injury meant Harlequins could bring their star fly-half Nick Evans, previously substituted, back on for a late drop-goal shot at glory.

Williams departed the pitch against Leinster accompanied by physio Steph Brennan, left, watched by the Sky Sports cameras

The convenience of Williams' injury raised eyebrows and suspicions.

"Who punched Tom Williams in the mouth, Tom Williams?" said former Bath and England fly-half Stuart Barnes as he commentated on Sky Sports.

Further along in the press box, Brian Moore was working for BBC Radio.

"What a load of rubbish. That is gamesmanship at best, downright cheating at worst," he said on air.

Down on the touchline, Leinster's staff were making a similar point, if in stronger language.

"As it was playing out [Harlequins director of rugby] Dean Richards was on the sidelines and I had a few words with him," says Ronan O'Donnell, the Irish side's operations manager.

"I'd probably have to bleep a few of them out. I just told him he was cheating and he knew he was cheating."

O'Donnell repeated his claim to one of the touchline officials.

"He showed me his fingers," remembers O'Donnell.

"He'd got some of the 'blood' on his fingers and it was like a Crayola marker had burst on his hands. It was that sort of texture and colour. He wasn't happy about it either."

Williams headed down the tunnel, surrounded by Harlequins staff. Members of the Leinster backroom followed in hot pursuit.

The truth went with them. But it didn't take long to emerge.

Bloodgate: The scandal that rocked rugby union

Richards was asked about Williams' apparent injury immediately after the match.

"He came off with a cut in his mouth and you have a right, if someone has a cut, to bring them off," he said.

"So your conscience is clear on that one?" persisted touchline reporter Graham Simmons.

"Yes, very much so," affirmed Richards.

The capsule was done, but the cover-up had begun.

Williams, by then, did have a cut in his mouth.

Locked in the home dressing room, while Leinster staff and match officials hammered on the door demanding entry and an explanation, he had pleaded with club doctor Wendy Chapman to use a scalpel to create a real injury in place of the fake one.

With the volume increasing outside, she reluctantly did so. A photo was taken as evidence to support Quins' conspiracy.

"We were trying to win and we thought nothing of it in terms of ethics," Williams tells Bloodgate.

"We thought we were just pushing the boundaries and doing what it took to try and get a result."

They had failed to do so on the pitch. A limping Evans had shanked a late drop-goal and Leinster hung on to win.

Soon, they needed to do so in a boardroom.

Three months after the match, Williams, Chapman, Richards and Harlequins physio Steph Brennan were sat in the plush offices of a central London law firm.

All faced misconduct charges. And a big screen.

The screen played television pictures which had never originally been broadcast.

They showed Brennan appearing to pass something to Williams as he went on the pitch to treat another player. Williams then appeared to fold the mystery object into the top of his sock.

And then finally, a few minutes later, the wing, kneeled, retrieved it and, after dropping it on the floor, placed it back in his mouth.

Together with the footage of him walking off the pitch, winking to a team-mate en route, it made a compelling case.

Dean Richards was a legendary player, winning 48 England caps and representing the British and Irish Lions, before moving into coaching

The club had its defence though.

Richards had co-ordinated their accounts.

Williams, they all claimed, had been retrieving his mouthguard from his sock. His mouth was already bleeding. Chapman had applied gauze to Williams' mouth, not a scalpel.

Richards called the charges against him and his club "ridiculous", claiming that fair play was "in-built" to his coaching.

Brennan, who had bought the capsule used by Williams from a fancy dress shop in Clapham, claimed never to have seen them outside of a Halloween party.

The panel presiding over the case were suspicious, but, with Quins' backroom staff sticking rigidly to their story, they couldn't unpick the full connivance.

"It was just so obviously a lie," says Williams. "I realised I was properly in trouble."

When the verdict came, it landed wholly on Williams. He was banned from rugby for a year. Richards, Chapman and Brennan were all cleared, with the club handed a 250,000 euro fine for failing to control their player.

WIlliams was, in the eyes of the adjudicating panel, a lone rogue agent.

Harlequins, united in both the crime and cover-up, were suddenly divided by a punishment that touched only one of their number.

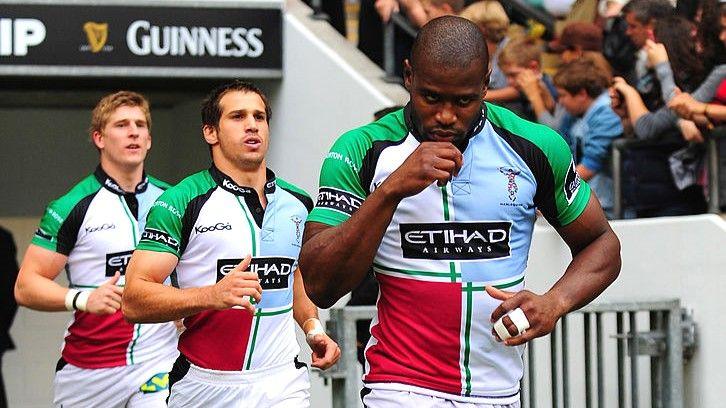

Ugo Monye, right, spent the whole of his 13-year professional career at Harlequins

Williams, having supposedly brought disgrace on Harlequins by independently concocting the blood capsule plan, sought advice from the Rugby Players' Association.

They urged him to appeal, to blow the whistle on the whole plot.

But the club had other ideas. Williams was offered a new two-year deal, three years of guaranteed employment at the club once he had retired and a promise to help him build a career outside of rugby.

He just had to hold back on the real story. He had to be a team-mate once more. He had to protect the club that meant so much to them all.

The full extent of the plot, the complicity of the club's medical staff and coaches, couldn't come out.

"They said to me 'do you understand the impact of this decision you're about to make? If you come forward and show this, Harlequins will be kicked out of Europe, your friends' playing opportunities for their countries will be reduced, Steph and Wendy will be struck off, we'll lose sponsors we'll lose money'," Williams remembers.

"Playing rugby was all I wanted to do and all I felt that I could do.

"So I was stuck between coming forward and telling the truth and falling on my sword. And I didn't know what to do."

"I'd have taken the rap," Ugo Monye, Williams' team-mate at the time, tells Bloodgate. "With the deal that was supposedly being offered, 100%."

The pressure was extreme.

Harlequins were desperate to contain a toxic scandal. Banned and branded a cheat, Williams wanted to tell the truth, explain his actions and rescue his rugby dreams.

At one point, he asked for more money in exchange for his silence; £390,000 to pay off his mortgage and a four-year contract. Quins refused.

In a statement from the time Quins chairman Charles Jillings described Williams' demands as "exorbitant" and "shocking". He insisted that "under no circumstances was the financial proposal a reward for Tom's silence."

"I'd sunk to rock bottom," says Williams. "It was a catastrophic period from a personal standpoint."

And all the time, the clock was ticking.

Williams had one month to appeal against his ban, to go public and get his career back on track.

Two days before the window to appeal shut, an email landed in Williams inbox.

He wasn't the only one considering an appeal. The European Cup organisers too were unhappy that he was the only person found guilty. They knew there must be more to the case.

The chances of one young player coming up with such a scheme on his own and carrying it out in secret in the tight and tightly-controlled environment of a professional club were remote.

They wrote to tell Williams they were to appeal against Richards, Brennan and Chapman being cleared. They would call him as a witness, cross-examine him and, if he didn't comply, level a second misconduct charge at him.

"His face literally just went white," remembers Alex, Williams' girlfriend at the time, now wife.

A final summit meeting with the Harlequins hierarchy was called.

Tom and Alex drove to the Surrey home of one of the club's board. Drinks and snacks were laid out, but the conversation soon turned to business.

"We were going round and round in circles," remembers Tom.

"Harlequins were saying to me, if I fell on my sword, for want of a better term, they would guarantee me future employment, pay off some of my mortgage, pay for me to go on sabbatical and we'll guarantee my girlfriend's future employment.

"On the other hand, if I came forward and told the truth they said l would bury the club."

Frustrated, stressed and tired after three hours of back and forth, Alex excused herself for a cigarette break. As she stubbed it out and prepared to go back into the meeting, she saw Tom coming in the opposite direction.

He had given up. He would run away, leave the country, turn his back on rugby, start again - anything to get out of this situation.

Alex hadn't finished though. She wanted to ask one more question of the 13 men in the room.

She walked back in.

"I remember the surprise on their faces when it was just me standing there," she says.

"I said 'I'm really sorry to bother you again, but do you mind if I just have you for a couple more minutes? I just want to ask you all individually one question'.

"I went round and I actually pointed to every single person and I just said, 'Is this Tom's fault?' And each of them gave a resounding no. Every single one of them."

"Alex humanised me again, because I had dehumanised myself, Harlequins had dehumanised me," says Tom.

"I was a pawn by that point, and I was ready to be moved in any way that anyone pushed me.

"She was the person from outside of this tight rugby centric-environment who could cut through that.

"She said what had gone on was not my fault - what had gone on was wrong - and made people realise that."

Then-Leinster coach Michael Chieka, far right in black coat, was keen to make his point to match officials as Tom Williams headed for the dressing room

Early the next morning, Tom got a phone call.

Richards had resigned. Harlequins said they would support Williams telling the truth and accept the fall-out.

The game was up. The cover-up would be uncovered. The truth would change lives.

At a hearing in Glasgow, Williams told the full story.

Richards admitted instructing physio Brennan to carry the blood capsules in his medical bag "just in case". He was judged to be the "directing mind" of the Bloodgate plot and banned from rugby for three years.

Brennan admitted buying the fake blood in advance and was described as Richards' "willing lieutenant". He was banned from the sport for two years and a dream job working with England, all lined up, was gone.

Harlequins' club doctor Chapman was referred to the General Medical Council. By cutting open Tom's mouth, she had contravened a central principle of medicine to "do no harm".

She said she was "ashamed" and "horrified" by what she had done, but she had an unlikely supporter.

Arthur Tanner - the Leinster doctor that day at the Stoop, one of those incensed by Tom's fake injury - spoke up for her.

"When it transpired that she had been forced and coerced into doing it I really felt very, very sorry for her because I realised there was going to be a difficult two or three years ahead of her," he said.

Tom, who had pleaded with Chapman to cut his mouth, also supported her, telling the hearing she is "as much a victim in all this as me".

"It's a huge regret of mine... putting her in a position where she felt she had no other option but to do it," says Tom.

Chapman was cleared to return to medicine.

Of the quartet though, Williams was the only one to stay at Harlequins.

At the first game of the following season, some opposition fans turned up dressed as vampires.

He was targeted on the pitch, with opposing players aiming taunts, and sometimes punches, at him.

There was no sanctuary in the home dressing room either.

"A number of my team-mates would have been loyal to Dean Richards and felt that I'd betrayed not only him, but also them as a club," remembers Williams.

"It definitely impacted them, there was definitely a level of distrust, probably dislike as well."

Williams became a quieter, sadder, slower presence. The zip was gone from his game, the smile was gone from his face.

It seemed he was just playing out his contract, an unwanted reminder of the past as Harlequins built an exciting new team under new boss Conor O'Shea during the 2011-12 season.

"I'd lost every morsel of confidence that I possibly could have had," remembers Williams.

"I wasn't in the team. I was just that person around training who had done something in the past."

But, after a starring cameo in a win over French giants Toulouse, something reignited in Williams' game.

The season ended with Harlequins winning their first Premiership crown in the Twickenham sun, with Williams scoring the first try in front of Alex and their young son.

"It's curious how sport works, how life works out," says Williams.

"You go from dead and buried to feeling the elation of being on top of the world."

Williams scored the opening try for Harlequins in the 2012 Premiership final

But you can also go in the opposite direction.

Williams played for Harlequins until 2015 when moved on to the coaching staff. In 2019, he left rugby to pursue a career in consultancy.

"About five years ago, I was diagnosed with depression and anxiety, and I suspect that it came from this event," he says.

"I've been on medication ever since, and I struggle on a day-to-day basis.

"My initial impression is always to trust, and that got me in trouble in the first place - but it's how I operate best. I try and see the best in people.

"I try and see the best in everyone involved. And I wish them the best because there's no point holding on to it.

"Ultimately, it was a game of sport, but it did mean everything to me at the time.

"I wish I had the self-awareness and perspective I have now.

Tom Williams on the legacy of ‘Bloodgate’

"I am very, very happy now. I've got three children who are healthy and happy, and I feel like I'm building a life for myself that isn't identified by a moment in time in 2009."

Escaping the taint of what spilled from the capsule and cut that day has been hard for all involved.

Dean Richards and Mark Evans both declined to be interviewed for this podcast series. Steph Brennan did not respond to our requests, while Dr Wendy Chapman could not be reached.