'Even when Muhammad Ali was robbed of his full voice he still moved people'

- Published

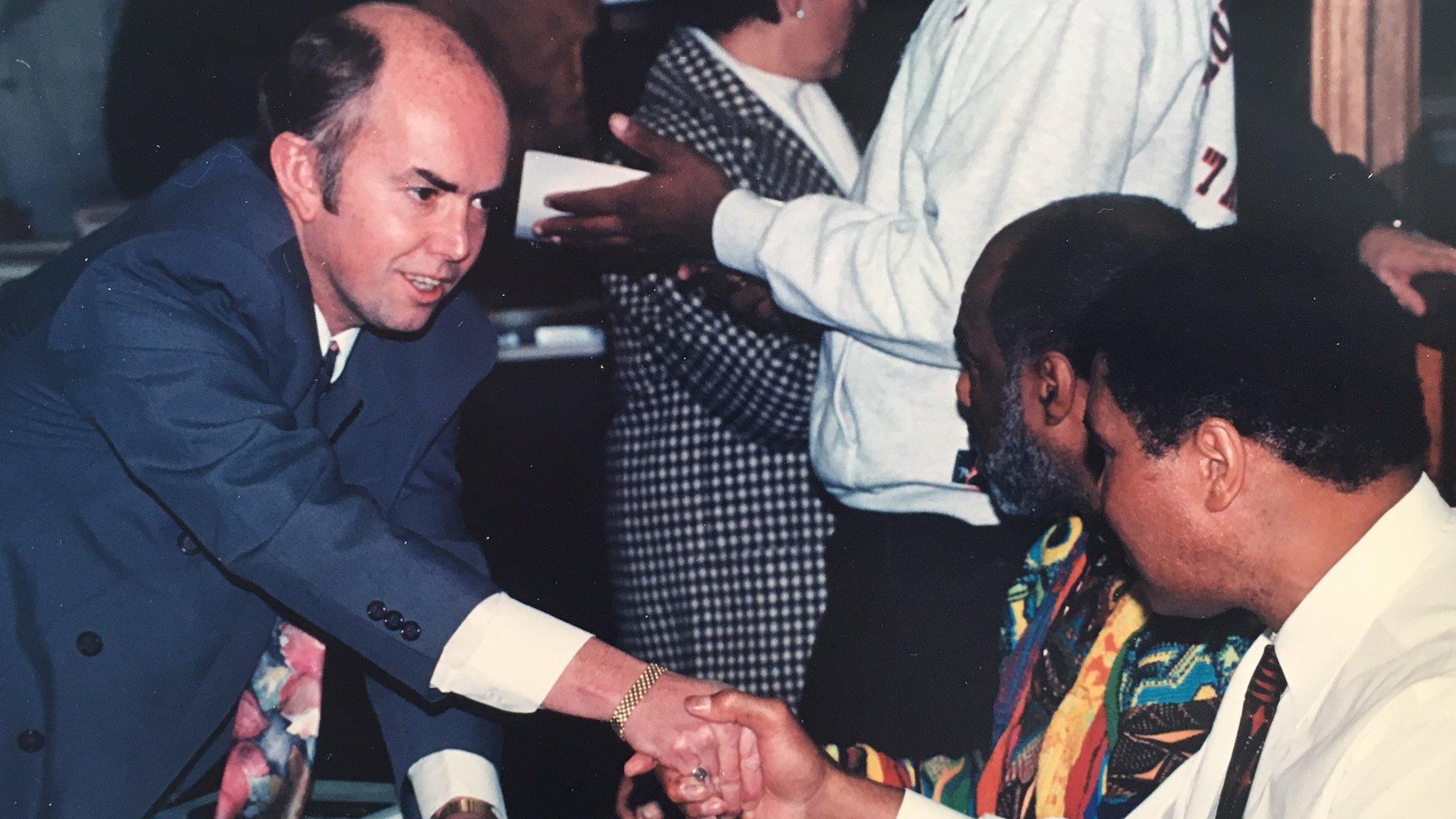

Muhammad Ali arrives in Glasgow in 1965 as heavyweight champion of the world to box in exhibition matches.

The queue snaked out of the side door of the book shop, 50 yards down the street, 100 yards down one side of an alleyway, 100 yards back up the other side and down the street again.

It was 1993 and Muhammad Ali was in Glasgow signing books with his friend, the photographer, Howard Bingham.

We stood in that queue for three hours or more, people of all ages chatting about Ali and what he meant to them. There was an old man there - maybe 80. Twenty-three years later and his face is as clear in the mind's eye as it was then, when we inched our way forwards and listened to his stories.

This was no braggadocio. As Ali once said, 'It ain't bragging if you can back it up'. And that Glasgow man could definitely back it up. He spoke about being at Wembley when Clay beat Henry Cooper in 1963, about being at Earls Court when Ali took apart Brian London in 1966, about being in Dublin when Ali did Al 'Blue' Lewis in 1972.

He knew it all. He spoke - quietly and not at all boastfully - about attending Ali's fight with Karl Mildenberger in Germany. None of us so-called Ali aficionados in that slowly moving line had ever heard of Karl Mildenberger.

So when Ali's people lowered the boom about his death at the weekend, one of the first thoughts was for that wee man in 1993 and what happened when we eventually got to the top of the queue and entered the bookshop, like children heading into Santa's Grotto.

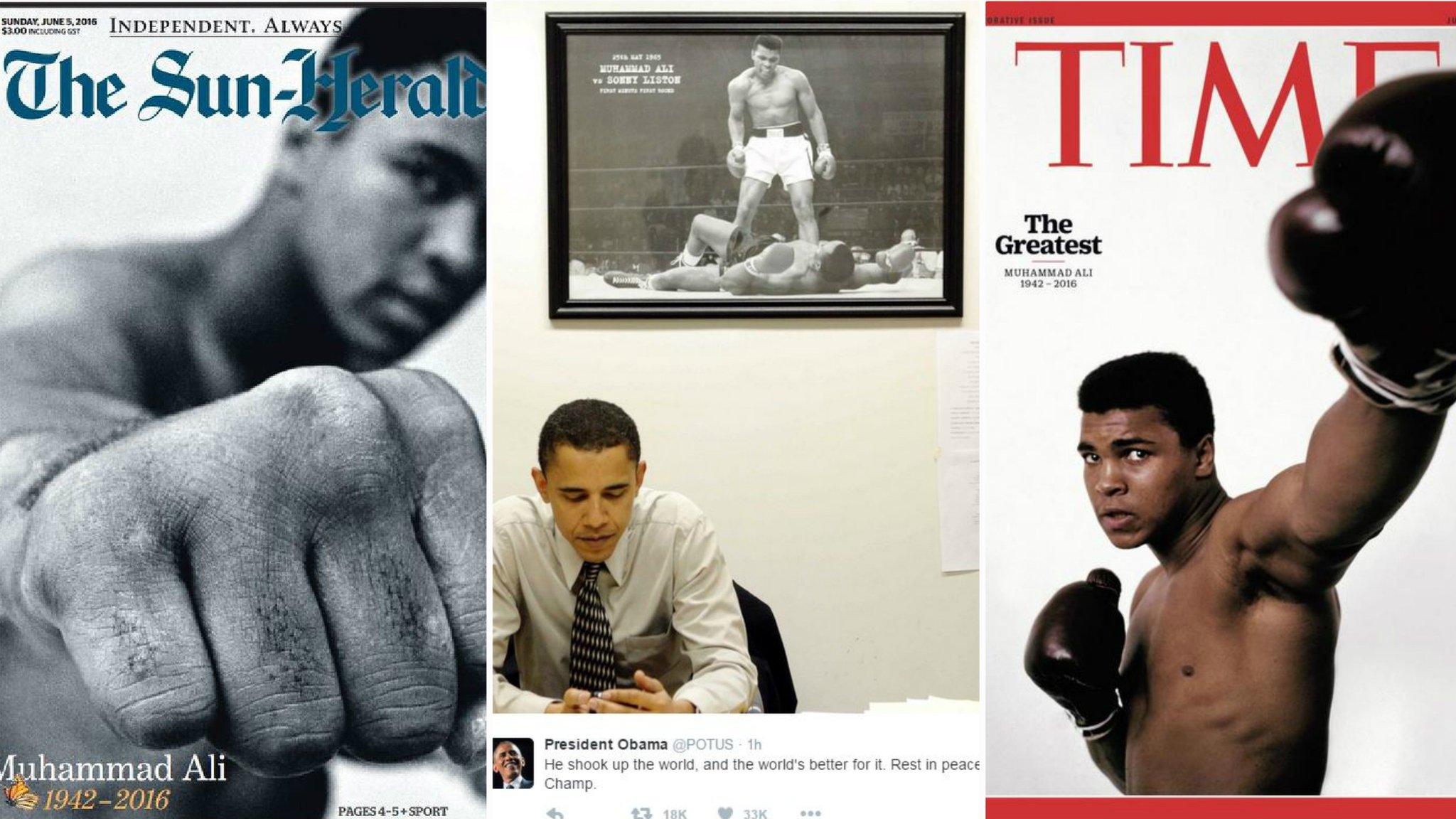

A look back at the life of boxing legend Muhammad Ali

He did not ask for Ali's autograph or take his picture, he just stood away at the side and watched Ali do his thing. Then he became emotional. And Ali noticed.

Ali was exhausted - he should have been out of there hours before but he promised to stay until the last person left - and he did not have the strength to speak, but when he got up to leave he looked over at the old man, smiled as much as his illness would allow and then slowly put his up his fists, as if challenging him to a fight.

The old man did the same - and smiled back. It is funny the things you remember, but that one tender and fleeting image is impossible to forget.

No words were exchanged, but none were needed. Ali was the most eloquent man in the history of sport, but even when Parkinson's robbed him of his full voice he still moved people with the simplest gestures.

Since his death, the eulogies have come thick and fast from all corners of the world and all spheres of society. There was not a nook or cranny on this planet that his legend did not reach.

For the best part of half a century he has inspired not just great sports writing but great literature. Hugh McIlvanney, Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Norman Mailer, George Plimpton, Pete Hamill, Hunter S Thompson, Mark Kram, David Remnick, Thomas Hauser - all heavyweights in their own game, all with a body of work that will keep Ali's complexity and the epic sweep of his personality alive for eternity.

The Greatest, in his own words |

|---|

"It's hard to be humble when you're as great as I am." |

"Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, his hands can't hit what his eyes can't see." |

"I'm the boldest, the prettiest, the most superior, most scientific, most skilfullest fighter in the ring today." |

"If you even dream of beating me, you better wake up and apologise." |

"Will they ever have another fighter who writes poems, predicts rounds, beats everybody, makes people laugh, makes people cry and is as tall and extra pretty as me?" |

In looking back on his life, you have to look at the whole life, not just the best of it. Hagiography has no place in the Ali story. To accentuate the greatness at the expense of the ugliness would actually diminish what he was.

Ali was the most remarkable sportsman in history but he was also, at times, one of the most bigoted, one of the cruellest, one who preached love but delivered hate on to men like Joe Frazier, a man who tried to help Ali at his lowest ebb and got little back apart from racial hatred.

Ali became world champion in 1964 when shaking up the world in victory over Sonny Liston. He defended his title against Liston in 1965, the same year he came to Scotland to fight exhibition bouts at the Paisley Ice Rink.

Even by then he was in the grip of the Nation of Islam, a frightening mob made up, in part, of ex-cons who preached a doctrine of separation of black and white. The integration of the races was a sin and they used Ali for all he was worth to get their message out there. No better man, no bigger audience.

This was one of the many contradictions of Ali. He was, as he said, free to be who he wanted to be, but he was not free at all in that period of his life, he was being manipulated remorselessly; ideologically and financially. The Nation got into Ali's head - and his bank account - to such a degree that he was, by the mid-1960s, espousing the view that any black person who had sexual relations with a white person should be killed.

Archive: Stars tributes to Ali at 70

He carried on that hateful mantra for years. You look at some of the television interviews he did with Michael Parkinson back then and you get chilled to the bone by Ali's thoughts. He came across as a Ku Klux Klan member in reverse.

The complexity of the man was profound. In 1967 - when still world champion - he appeared in front of the US Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in Houston. The army wanted to enlist Ali for the war in Vietnam that day. If he had taken a step forward when his name was called out he would have been on the first bus out of Houston bound for Fort Polk, Louisiana and then onwards to Vietnam.

Ali never took the step. Everybody knew he was not going to take it. The FBI had his every move under surveillance. They regarded him as a subversive.

As soon as Ali conscientiously objected to the draft - 'Man, I ain't got no quarrel with them Vietcong' - he was aware of what was coming.

The backlash was seismic. His title was stripped, his reputation trashed by white America and his life put at risk. He was not allowed to leave the country. Red Smith, one of the most influential sports columnists of the age, took out a literary blow-torch and let Ali have it. "Squealing over the possibility that the military may call him up, Cassius makes himself as sorry a spectacle as those unwashed punks who picket and demonstrate against the war," he wrote.

Ali's boxing career | |

|---|---|

Born in Louisville, Kentucky on 17 January 1942 | Turned professional later in 1960 and was world heavyweight champion from 1964 to 1967, 1974 to 1978 and 1978 to 1979 |

Won Olympic light-heavyweight gold in 1960 | Had 61 professional bouts, winning 56 (37 knockouts, 19 decisions), and losing five (four decisions, one retirement) |

Ali was branded a coward and a phony. David Susskind, the famous American television presenter and political commentator, went on TV with Ali and branded him "a disgrace to his country, his race and what he laughably describes as his profession". Susskind called Ali a "simplistic fool" who ought to be jailed.

Time proved Ali right, of course. It cost him almost four years of his career and an estimated $10m, but his principled stance became a hallmark of his greatness - or one of them.

Ali said that he was prepared to die for what he believed in. Nobody doubted that there were people out there in 1960s America who would have wanted Ali dead.

Ali was suspended from boxing on April 28, 1967 and returned with a fight against Jerry Quarry on October 26, 1970. Those around him said then, and they've been saying it ever since, that the three-and-a-half years he lost would have been his peak years. Ali knew it, too. Not that it stopped him marching onwards into boxing history.

He now entered the Joe Frazier years - The Fight of the Century at Madison Square Garden in 1971, the Thrilla in Manila in 1975 and, in-between, the Rumble In The Jungle - the reclaiming of his world title against George Foreman.

Ali versus Frazier - the blood feud trilogy - has spawned books and films and every new one that comes out adds another layer to what is surely the greatest rivalry in sporting history.

Ali would come to regret his treatment of the great rival of his career Joe Frazier.

What Ali did to Joe was shameful - and he was remorseful about it until the end. Joe lent Ali money and helped him get his boxing licence back. He went to the White House and asked president Richard Nixon to help Ali out. Joe did not agree with Ali's stance on Vietnam but he felt it wrong that he was banned because of it. "Not right to take away a man's pick and shovel", was his immortal line.

Ali forgot all of that. When he fought Frazier first, in 1971, he belittled him in public. He called him dumb and ignorant and ugly. He called him ape man and the gorilla. Through the force of his oratory, Ali turned black America against Frazier. He said that anybody who supported Frazier was a traitor.

"The only people rooting for Joe Frazier," said Ali, "are white people in suits, Alabama sheriffs and members of the Ku Klux Klan. I'm fighting for the little man in the ghetto."

Frazier was presented as an Uncle Tom - a grotesque distortion of his life, which was entrenched in the kind of poverty that Ali never knew. Their three fights were savage. "The closest thing to dying," as Ali put it. Frazier was prepared to die, no doubt about it.

Muhammad Ali was awarded with the BBC Sports Personality of the Century

Right to the end of his own life, in November 2011, Frazier held a grudge against Ali. He used to speak about Ali's Parkinson's and the fact that he could not talk much anymore and he would mock him. He would say that God sent him to fix Ali. "He sent me to get him. I don't think that, I know that."

Ali said sorry to Joe many times over the years. He felt guilt and tried to make amends. It never quite worked out with Frazier, not in this world at least.

As he got older Ali became all about tolerance and love. All the hard edges softened and then disappeared. He lived out his life as a fighter of another kind, not the Louisville Lip, but a crusader against racism, injustice, crime, illiteracy, poverty. Those things, you sense, were of far greater importance to him than anything he achieved in the ring, from his first professional fight against Tunney Hunsaker at the Freedom Hall in his hometown of Louisville to his last, against Trevor Berbick, 21 years later.

"This life is nothing but a fraction of a second compared to eternity," Ali once said. "You give God one good second and God will give you heaven for eternity."

- Published5 June 2016

- Published4 June 2016

- Published4 June 2016