World snooker runner-up Judd Trump still a winner

- Published

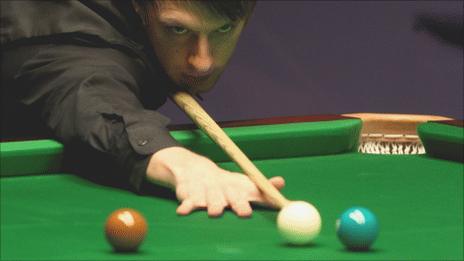

Trump - New kid on the baize

Judd Trump may have come up short in a compelling World Championship snooker final on Monday but he succeeded in wowing the sporting world.

Audiences have been electrified by the audacity of his potting, the intricacy of his spatial awareness and the effortlessness with which he seems to encompass the complexities of the ancient game.

And the Bristolian is only 21. Had he won, he would have become the second youngest champion in history, a fact that left many commentators breathless with admiration.

To see any youngster playing well is impressive but to see a chap barely out of adolescence coming within an ace of the ultimate prize is close to mind-bending.

It leads to an almost irresistible conclusion - it is all about talent.

It is the idea that sporting precocity is written into the genes. As Dennis Taylor, the former world champion, put it: "Trump was born to pot snooker balls."

Similar explanations were trotted out when Tiger Woods became the youngest winner of the US Masters in 1997 and when the Williams sisters exploded on to the tennis circuit. They are also used to explain precocious performances in music, mathematics, chess and much else besides.

But there is a problem with this otherwise seductive explanation, it is profoundly wrong.

When you dig down into the biographies of so-called prodigies, there is simply no evidence of children floating to the top via the buoyancy of superior genes. Instead what you see is eye-watering quantities of hard work compressed into the period between birth and adolescence.

Woods, for example, was given a golf club five days before his first birthday, played his first round at two and had accumulated more hours of practice by five than most of us achieve in a lifetime.

Far from being a golfer zapped with special powers that enabled him to circumvent practice, Woods is someone who embodies the rigours of practice.

A strikingly similar story emerges whether you look at the Williams sisters, Lionel Messi or, for that matter, Mozart.

And it is a story that also emerges for Trump, who was given a miniature table at the age of three and who proceeded to clock up astronomical amounts of practice, defying the expectations of his parents, who assumed he would quickly get bored.

Higgins 'the better player' - Trump

At the age of six Trump graduated to a local club, standing on a box to see over the table, and at eight he had started to play in proper competitions.

Excellence was not achieved rapidly, or even steadily, but painstakingly. His father has said he can still remember his son spending hours on his little table potting balls and that he would keep working until he got it right.

The very idea of talent is profoundly misleading. We infer talent because we only see a tiny proportion of the work that goes into the construction of virtuosity.

If we were to examine the thousands of baby steps taken by world-class performers to get to the top, the skills would not seem quite so mystical, or so inborn.

This is not to deny that some children start out better than others, it is merely to suggest that the starting point we all have in life is not particularly relevant. Why? Because over time, with the right kind of practice, we change so dramatically.

It is not only the body that changes but the anatomy of the brain. A study of London taxi drivers, for example, discovered that the area of the brain governing spatial navigation is substantially larger than for non-taxi drivers - yet maybe it did not start out like this, but developed with time on the job.

Child prodigies like Trump and Woods have led the world down a blind alley. They have deluded us into the idea that excellence is reserved for a special breed touched by a genetic miracle that passed the rest of us by.

The evidence is quite the reverse: we all have the potential for excellence, provided we persevere along the path of personal transformation.

Think how often you hear children say they do not have a brain for numbers or they lack the co-ordination for sports.

These are direct manifestations of the talent myth: the idea that if you do not speed to the top, you must lack talent, and if you lack talent, you may as well give up. It is a mindset that destroys motivation.

Trump did not think like that. He believed that talent could be built over time - and he was right.

Had he failed to put in the hours, he would not have made it past qualifying, let alone to the brink of his first world title.

Matthew Syed is the author of Bounce: The Myth of Talent and the Power of Practice

- Published3 May 2011

- Published2 May 2011

- Published30 April 2011

- Published20 April 2011

- Published25 April 2011

- Published10 April 2015