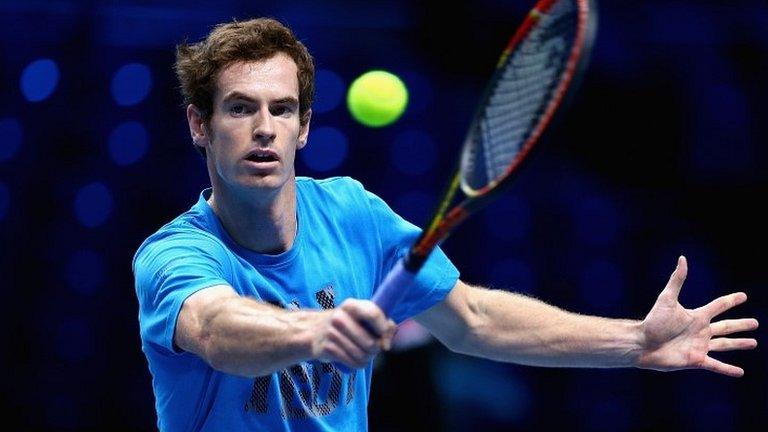

Andy Murray: Wimbledon victory the 'holy grail' for British sport

- Published

- comments

Highlights - Murray wins Wimbledon title

Stop the clocks, lob the history books onto the fire. Pinch yourself, and then again.

To be British and in love with sport in this age is to be blessed beyond the dreams of our long-suffering ancestors.

In the space of 12 months we have witnessed the nation's greatest Olympics, its first ever winner of the Tour de France and now, in Andy Murray's crowning as Wimbledon men's singles champion, the greatest hoodoo of all blown apart in glorious, giddy style.

The moment Murray won Wimbledon

London 2012 gave us Super Saturday, that dizzy procession of Olympic golds that might never be topped. This was Surreal Sunday, a day many thought they would never see and one that seemed scarcely real even as it was unfolding.

Men have lived and died waiting for a British man to win Wimbledon, so let us note for posterity how it finally came about: a forehand from Murray deep into Novak Djokovic's backhand corner, a weary reply into the Centre Court net.

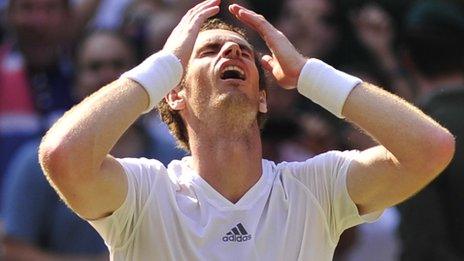

After 77 years of waiting, no-one knew quite what to do. So long has this moment been dreamed of, so often has it seemed impossible, that the magnitude of it all threatened to overwhelm both Murray and his adoring public.

This title has been the lost ark of British sport, the holy grail thought gone for good. For it to be reclaimed in straight sets, just as it had last been won by the great Fred Perry,, external was the final bewildering twist in a tournament where so much made such little sense.

Neither, despite that seemingly straightforward 6-4 7-5 6-4 scoreline, could the ending be anything but tortuous. At 40-0 in the final game Murray lost first one championship point, then another, then another.

Djokovic, freed at last from the shackles that had bound in the previous three hours, then threw caution and the kitchen sink to the breeze and set up three break points with the sort of clean hitting that had taken him into the final only to abandon him on the day.

Andy Murray expresses delight after 'unbelievably tough match'

For the thousands around the court and millions watching from home, it was almost too much. Not now, not on the brink, not after hope had first elbowed away the anxiety and then bloomed into outright belief.

Murray, like the champion he now is, would not wilt.

"That last game pretty much took everything out of me," he admitted afterwards. "I was just thinking if this goes the other way I don't know what is going to happen."

That he found a way to come through was entirely fitting after a performance where he refused to buckle, neither under the weight of national expectation nor when Djokovic, after an uncharacteristically error-strewn start, started throwing the sort of punches that would have floored any other opponent.

Murray, just as he had in his four-set defeat by Roger Federer in the final of 2012, had seized the first set, his 17 winners a sparkling contrast to Djokovic's 17 unforced errors. When the Serb went 4-1 up in the second, history appeared ready to repeat rather than stand aside.

This time he would not submit. First he broke the six-time Grand Slam champion back and then, at 3-4 and facing repeated break points, hung on and on before accelerating away as Djokovic faltered again.

At times it was brutal, just as contests between these two always seem to be. Rallies routinely went past 20 shots. At one point the temperature in the fierce sunshine was reported to be 49C.

If that made it the hottest Wimbledon final since 1976, the support from the Centre Court stands blistered the grass still further. Murray, not always loved unequivocally by his public, was roared on unrelentingly. Henman Hill, a ripening field of waving arms and pinking noses, was in booze-soaked ferment.

Britons have always loved sport like few others. Now, thanks to Murray and his fellow elite performers, they have the global successes to match the national passion.

It is a golden period to be cherished and celebrated, an era of Ryder Cup miracles and Major-winning golfers, of world champion cyclists, rowers and triathletes, of a series-winning Lions squad for the first time in 16 years and a cricket team that has won back to back Ashes series, external and could do so again. If the various national football teams still seem intent on pooping the party, at least we're relatively accustomed to it.

Murray, in the middle of all that, famously won the US Open to lift the country's 74-year Grand Slam curse. In winning Wimbledon he has achieved something with a resonance beyond the confines of his chosen sport.

Those of superstitious bent were claiming it was written in the stars: 77 years of Wimbledon waiting, the last home-grown champion Virginia Wade in '77,, external the date of this final the seventh of the seventh.

But this was never preordained, nothing else but the culmination of a lifetime of relentless work and ceaseless ambition.

It took him eight attempts to win Wimbledon, four semi-finals to make the final, another to finally step onto the summit. As a teenager he moved far from his Scottish home to learn the ropes in northern Spain; as an adult he has sacrificed any semblance of a normal life in order to drive himself from top 10 to top four and now, onto top one?

There will be plenty of talk of what more he can go on to achieve, of how many Grand Slam titles he can add. So too will there be debate about where this puts him in the pantheon of British sporting greats.

For now, we should delight in what it means for his home town of Dunblane, for the usually dismal state of tennis on these shores and, most of all, for one supremely talented, often introverted kid from a sleepy part of Scotland who grew up dreaming of a day like this.

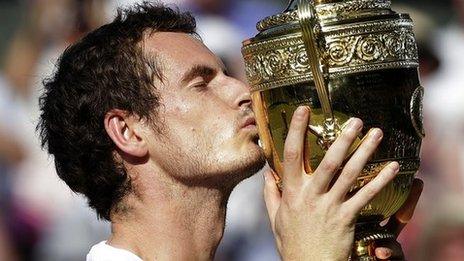

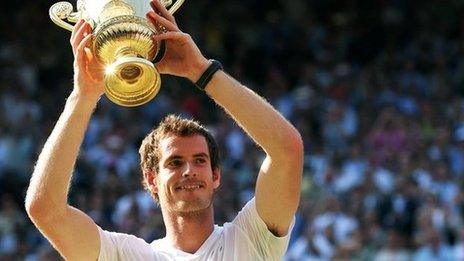

On a perfect day, he provided the perfect ending: standing under a cloudless summer sky, arms aloft, that famous golden trophy glinting in the warm July sun. In an age of special sporting memories, one to stay with us to the end.

- Published7 July 2013

- Published7 July 2013

- Published7 July 2013

- Published7 July 2013

- Published7 July 2013

- Published7 July 2013

- Published7 July 2013

- Published6 July 2013

- Published17 June 2013

- Published9 November 2016

- Published30 May 2013

- Published30 May 2013