Andy Murray: Why Scotland adores one of their favourite sons

- Published

- comments

When Andy Murray was a 14-year-old tennis star of the future

As the trophies give way to tears, tennis boffins the world over are currently cataloguing Andy Murray's greatest days on a court, the many moments of majesty that define him as one of the finest players in the history of the game and one of the most significant in the history of Scottish sport.

US Open champion, double Wimbledon champion, double Olympic gold medallist, 11 Grand Slam finals, former world number one, behemoth of the Davis Cup. Put the kettle on, pull up a chair and take your pick of his best moments. While you're at it, consider this other contender from left-field...

No trophy on offer this time. No packed court. No worldwide audience. We're going back to 2015. Murray has slipped back into Scotland to spend Christmas with his mum in Bridge of Allan.

It's Boxing Day morning. And it's dreich. Murray sticks on his training gear and his beanie and goes for a run. He heads out of Bridge of Allan, up to the roundabout and down the hill into Dunblane. He does a circuit of his old town and then begins his return, a route that takes him by the tennis club where it all started for him as a child.

There are some kids in there, playing in the gloom. He stops and looks awhile. Then he opens the gate of the court, takes off his beanie and asks if they'd mind if he had a hit with them. There are no journalists there. No cameras, no crowds to witness the presumably disbelieving delight of the children.

We all know about Murray the athlete, but this tells us something about Murray the person. The story only emerged many months later, via his mother or his grandparents, it's hard to remember now. Murray would probably rather it never got mentioned, but what an image that is. Murray and these kids hitting balls together in the rain. The thought of it, in some senses, is every bit as inspirational as all those great moments in the sun.

Giving Dunblane new meaning

Murray is adored in his hometown of Dunblane, where he received a golden postbox after winning Olympic gold

Murray's on-court brilliance, the big titles, the glittering trophies. There's more to the Murray Effect than that. A lot more.

There's a story worth telling here and it took place far away from the glamour of Centre Court, in an estate in Kennington in south-east London. It was the early afternoon of Monday, 8 July, 2013. Fewer than 24 hours earlier, Murray had become the first Briton in 77 years to win the men's singles at Wimbledon.

Between defeating Novak Djokovic in the final, then doing his myriad news conferences, then partying, then doing more news conferences, he'd barely slept and yet at lunchtime on the Monday, Murray was hitting tennis balls again.

It was something to see. A temporary court had been constructed in the middle of a flats complex. Dozens of kids from four local primary schools were in attendance. They were nervous and giddy and delightful - and Murray looked to be in his element among them.

There was a girl called Elisa and a boy called Azriel. They can't have been any more than 10 years old. Elisa asked me where I lived and I said I lived near Dunblane, in Scotland. "You live near Dunblane!" she shrieked. "No way! You really live near Dunblane? That is so cool."

When inner-city London kids whooped and hollered at the mention of Dunblane then you knew something remarkable had happened. When, with racquets in hand, they asked what it's like in Dunblane in the manner of children enquiring about the wonders of Disneyland, then you knew that what Murray did the day before had a wider significance.

To Elisa and Azriel and their many friends, Dunblane had taken on new meaning. To them, it wasn't the place defined by tragedy. It was Andy Murray's hometown and that's something they wanted to know about.

Sure, this was an event put on by one of his sponsors, but there was an energy in Murray and an innocence in the children that made it wondrous. There was nothing staged about their excitement and their awe at seeing the champion from the great mystical land of Dunblane.

Andy Murray: Wimbledon 2013 - the moment he won the title

Doping, politics & feminism - the brave advocate

We've come to marvel at Murray's greatness on a tennis court, but that's not the sole reason why he's so revered or why Scots look at him - as they might Billy Connolly - and say, "I'm proud to come from the same place as him".

If it was just pure sporting talent and not a lot else, he wouldn't command the warmth that he does. There's more - and those snapshots from Dunblane and Kennington talk to his wider appeal, his magnificence as a tennis player, yes, but also his essential goodness as a person.

Murray has been brave along the way. This is another thing that elevates him above many others. The scourge of doping in sport is not something that global superstars are minded to address for fear of compromising their finely sculpted, non-controversial PR image, but Murray has been there numerous times.

No doubt, his advisors would have preached caution, but when others sat on their hands on the doping question, Murray took a stand. He criticised tennis for its lack of testing. He spoke about cheating in a wider context. "The biggest cover-up in the history of sport," was how he described the saga of the doping doctor Eufemiano Fuentes, the affair that saw blood samples of suspected dopers from many sports go unexamined after a controversial ruling in a Madrid court.

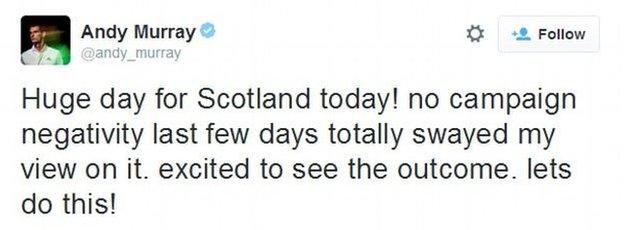

Whether you agreed with his politics or not, Murray coming out in favour of Scottish independence on the eve of the 2014 Referendum was an illustration of his courage. He must have known that entering such a minefield might hurt his image in the eyes of some, but he spoke up regardless. Many in his position would have listened to the publicists and kept his head below the parapet.

Murray became more than just a tennis champion. In 2014, when he hired the two-time Grand Slam women's champion Amelie Mauresmo as his coach, he broke new ground and set off on a journey that would soon lead to him being celebrated as one of the great advocates of women in sport and one of the strongest voices on the staggering sexism that exists in tennis.

The Scot spoke about the prejudice that Mauresmo suffered as his coach, a prejudice that his male coaches never experienced. He said he felt embarrassed at some of the things that the Frenchwoman had to contend with, the casual sexism that drove him nuts and that he railed against.

When an interviewer congratulated him on becoming the first person to win two Olympic titles, he pointed that the Williams sisters had won more. When a journalist referred to Sam Querrey as the first American player to reach the semi-final of a Grand Slam in years, Murray shot back: "Male player. The first male player."

Andy Murray corrects journalist over gender claim

He championed women tennis players getting more game-time on Wimbledon's Centre Court. He called for equal pay when others procrastinated. He highlighted the lack of opportunities available to women coaches. "Have I become a feminist? Well, if being a feminist is about fighting so that a woman is treated like a man then, yes, I suppose I have."

Murray's time as an elite player is coming to an end, but the excellence and passion he showed in winning all those titles across all those years are only part of why he is adored in Scotland and beyond.