Olympic Games: The daring escape sparked by one forbidden glance

- Published

Raed's mind was racing as he carried his country's flag that day

"Do not look at President Clinton."

Those were the instructions Raed Ahmed was given before the opening ceremony of the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

The stocky Iraqi weightlifter was told that Clinton and the United States wanted to destroy his country and should be shown no respect. The message had come from Iraqi Olympic Committee officials, who were under the orders of Saddam Hussein's eldest son, Uday.

"They said don't look left or right because the president is going to be there, don't look at him," Raed says.

"I said no problem."

Raed beamed as he jogged into the stadium, proudly holding his national flag. Then aged 29, he had been chosen for the honour before two others.

Despite having the eyes of Iraqi officials fixed on him, he glanced to his right.

"I couldn't believe it," he says. "Clinton looked at us. I saw he was very happy when he saw us. He stood up and was clapping."

It was a moment that changed Raed's life forever.

Born into a Shia Muslim family in the Iraqi city of Basra in 1967, Raed's father was a bodybuilding coach. He started making his own name in weightlifting in the early 1980s; in 1984 he was crowned national champion in the 99-kilogram category.

But his sporting success was taking off against a backdrop of turmoil in his homeland.

In 1991, there were rebellions by Shia Arabs in Iraq's south and Kurds in the north.

The rebellions began in the immediate aftermath of the first Gulf War when Iraqi forces that had invaded Kuwait the previous year were routed by a US-led multinational coalition.

In mid-February 1991, days before the start of the coalition ground assault, then US President George H W Bush broadcast a message telling Iraqis that there was a way to avoid bloodshed.

"That is for the Iraqi military and the Iraqi people to take matters into their own hands, to force Saddam Hussein the dictator to step aside," he said in a speech.

The Shia and Kurds believed this would mean the US would back uprisings against Saddam, and in March they erupted.

In Basra and other cities, hundreds of unarmed civilians spilled out onto the streets and took control of government buildings, freeing prisoners from jails and seizing caches of small arms. At its height, control of 14 of the country's 18 provinces had been wrestled from Saddam's forces and there was fighting within miles of the capital, Baghdad.

But as the uprising spread throughout the country, US officials insisted it was never their policy to intervene in Iraq's internal affairs nor to remove Saddam from power.

With the Gulf War over and the rebels lacking US support, Saddam unleashed one of his most brutal acts of repression against the Shia and Kurds, killing tens of thousands in just months.

Raed recalls witnessing Saddam's cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid, also known as Chemical Ali, who was tasked with putting down the rebellions, lining up students from the university in Basra and shooting them.

UN economic sanctions on Iraq also started to hit ordinary people hard. Raed says people were struggling to afford the most basic food like bread and rice.

He had already started to think about how to get out.

Saddam Hussein was executed in Baghdad in December 2006

Unlike most Iraqis, Raed had the opportunity to travel abroad for competitions.

But being an elite sportsman in Iraq meant coming face-to-face with Uday Hussein, Saddam's notoriously brutal son, who was president of the Iraqi Olympic Committee and Iraq Football Association.

Uday's punishments for infractions such as missing a penalty, receiving a red card, or underachieving included torture with electric cables, forcing people to bathe in raw sewage and even execution.

"He'd do whatever he wanted, he was Saddam's son," Raed says.

In an effort to protect himself, Raed would do his utmost to lower Uday's expectations ahead of international tournaments.

"I would see people when they got out of jail. Football or basketball players would tell us: 'Be careful when you go to competitions'. They killed many people," he says.

"When he asked if I could bring home a gold medal I'd say no. For a gold medal you have to work out for at least four years and it was too hard to do that in Basra - little food and water. To weightlift you need a lot of food and physical therapy."

Raed was increasingly seeing international competitions as the best way to get out of Iraq for good. He was training harder than ever, putting himself through two gruelling sessions a day, five days a week, in order to make the grade.

In 1995, he travelled to China for the World Weightlifting Championships, but felt the likelihood of Chinese officials handing him back over was too high to make an attempt at escape. His performance was good enough to secure a place on the Olympic team, though. He'd be going to Atlanta.

And he knew that the 1996 Games in the US would offer a better opportunity.

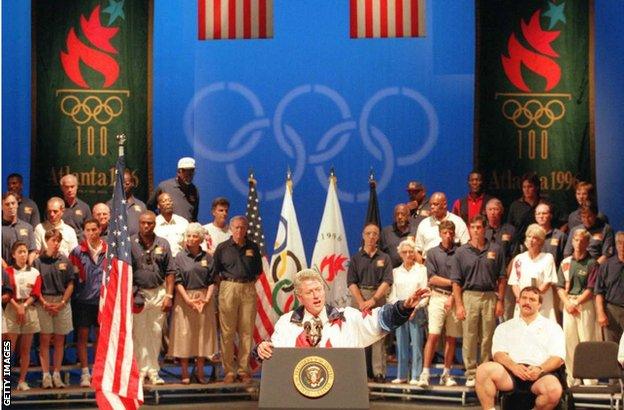

President Clinton gives a speech at the Olympic village in Atlanta, in 1996

Before travelling to the Olympics, Raed contacted a friend in the US. He started weighing up the risks. What if they sent him back to Iraq? What would happen to his family? How would he escape from the ever watchful eyes of the Iraqi officials? Raed wasn't sure whether an escape was realistic when he boarded the plane for America.

Upon arriving at the Olympic Village, Raed settled into his surroundings and tried not to raise any suspicion. After all, he had the responsibility of carrying his national flag at the biggest show on earth.

Before the opening ceremony, he was told repeatedly to not look at President Clinton by Saddam's former translator, Anmar Mahmoud, who had travelled with the Olympic team.

"They wanted to show that Iraqis do not like the United States, they do not like the president," Raed says.

Mahmoud was standing directly behind Raed as they paced around the Olympic track on 19 July 1996.

He says Mahmoud noticed that he was looking at Clinton, but he didn't say anything. The Iraqi officials also seemed genuinely surprised that the president was clapping them, he says.

Any remaining doubt in his mind was now gone - he wasn't going back to Iraq. But now came the problem of how to stay in the US.

Raed contacted another friend in the US called Mohsen Fradi and told him of his plan. Then, an engineering graduate from Georgia University by the name of Intifadh Qambar, who had access to the Olympic Village, came to visit.

Raed asked for help in getting him out. The pair met in secret, but his minders were becoming suspicious.

"The Iraqi Olympic officials started to suspect that I wanted to stay and they told me that I was not allowed to stay and that I would be jailed if I did," he says.

Raed was undeterred. The plan was set, but first of all he still needed to compete. Unable to prepare to the levels of his rivals, he finished third bottom of his weight class, lifting a total of 665.5 pounds in two separate lifts.

With the competition out of the way, it was time for his escape.

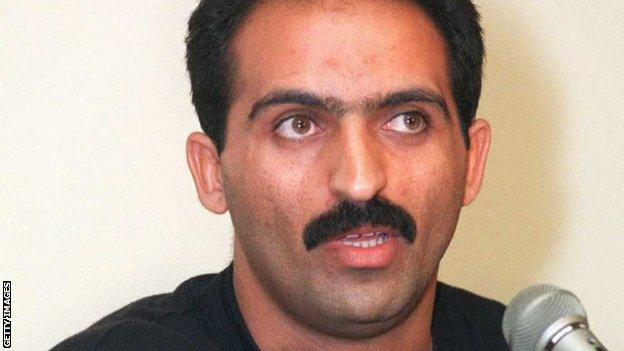

Raed pictured at the press conference held following his defection

On the morning of 28 July, 1996, the Iraqi Olympic team were preparing to visit a nearby zoo. As the team went down to have breakfast, Raed pretended he had forgotten something in his room.

He quickly packed his bags and rushed to the front of the Olympic Village. Waiting for him in a car were Qambar and Fradi. Raed hopped in and they drove away.

"My thoughts were with my family the entire time," he recalls. "I was worried about them and what would happen to them after the Iraqi officials found out I was escaping. I wasn't fearful for myself because I knew I was in good hands… and I wasn't in any danger here. The only fear and worry I had was for my family."

Raed - who left with no passport as the Iraqi officials kept hold of all of their documentation - went to meet an Iraqi-American lawyer who had travelled from New York and they went to an immigration agency to explain Raed's desire to stay in the US.

Then a press conference was arranged and he faced the world's media.

"I love my country. I just don't like the regime," the New York Times quoted Raed as saying.

After the press conference, Raed says Uday Hussein's office rang CNN and told them to pass on the message that he needed to come back because his entire family were being held hostage.

His family members were eventually released after Raed refused to return to Iraq, but he could not speak to them for more than a year.

"Things were very difficult for them, people didn't want to talk to them. My mum was a director at a school and they kicked her out," he says.

Once Raed was granted asylum he says he worked seven days a week so he could afford to pay for a fake Iraqi passport for his wife. In 1998, she managed to make it to Jordan, where they sought the help of United Nations officials before making it over to the US.

Raed and his children, pictured in 2019

Raed and his wife settled in Dearborn, Michigan, where they live to this day and have raised five children. Dearborn has a large Arab community, and since 2003 when the Iraq War began, thousands of Iraqi refugees have settled in the area.

"Dearborn is like Baghdad," Raed laughs.

He set up a used car dealership and continued training as a weightlifter. He also coached local Iraqi football and basketball teams.

Then in 2004, after the fall of Saddam Hussein, he returned to Iraq for the first time.

"All my family were waiting for me and they wanted to see me because I hadn't seen them since 1996. They were just crying when they saw me, they didn't believe they would ever see me again," he recalls.

Raed's parents still live in Basra, but they would visit the US every year before the pandemic hit.

Looking to the future, Raed thinks he will probably stay in Michigan, although moving somewhere with the temperatures of his homeland has always been alluring.

"I want to move to Florida because it is the same weather as Iraq," he laughs. "Here, especially in December to February it's very hard to live - there's a lot of snow and it's too cold. I had never seen snow before. I thought, how are people going outside in three or four inches of snow?'"

He says he will be tuning into the Olympic opening ceremony in Tokyo this July, as he always does.

"It's very nostalgic for me and reminds me of how far I've come. Every time I watch, I wish I was attending and participating in some way," Raed says.

"Watching it will truly take me back 25 years and I'm sure I'll be reliving my experience."