Elfstedentocht: The famed, frozen race that may never return

- Published

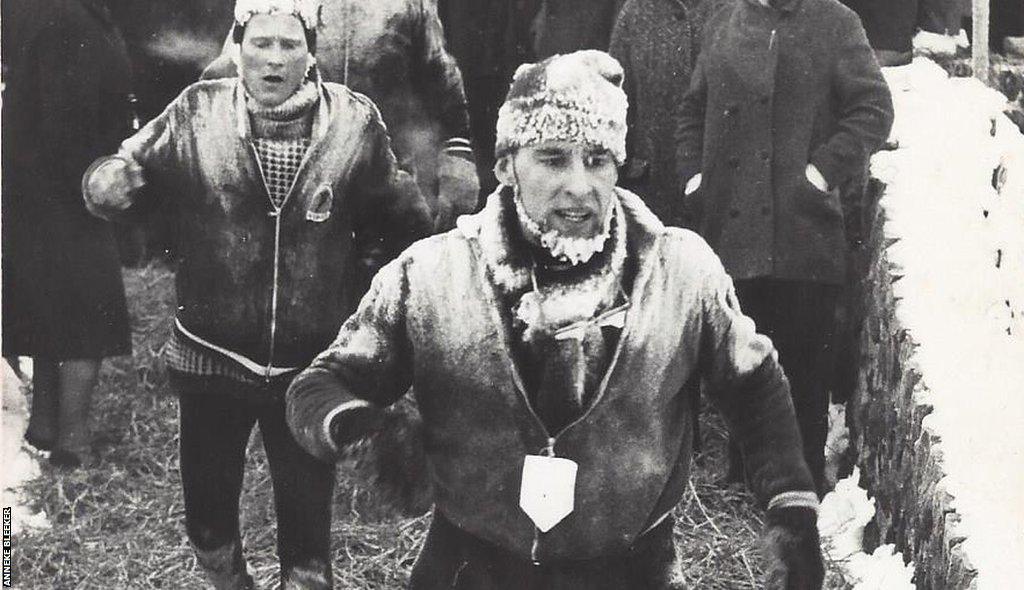

Leffert Oldenkamp (front) competes in the 1963 Elfstedentocht

Sign up for notifications to the latest Insight features via the BBC Sport app and find the most recent in the series.

"There was no other way but to get moving - otherwise you were freezing. And lots of people were freezing - frozen eyes, frozen toes, whatever. Your weak parts, frozen!"

It's 18 January 1963 and Leffert Oldenkamp is skating through the dark, freezing, foggy morning.

He has had next to no sleep, the temperature is a bone-chilling -18C, and the icy wind cuts through his clothes.

He is taking part in one of the toughest sporting tests there is - skating nearly 125 miles on uneven natural ice through the bleak, winter landscape of the Dutch province of Friesland.

This is the famous Elfstedentocht - the 'Eleven Cities Tour' - a test of physical and mental endurance like no other.

The 1963 edition proved so brutal that just a handful of people made it to the finish out of the thousands who started.

The winner, Reinier Paping, became a national hero. Oldenkamp was one of the few to follow him home.

Sixty years later, there have been only three subsequent editions of this astonishing event - the most recent way back in 1997.

Yet despite its rarity, it remains a national obsession in the Netherlands. When a cold snap comes, conversations turn swiftly to the ice: might it finally happen this year?

Those conversations are now tinged with the fear that the answer could be 'never again'.

Wiebe Wieling is a man with a highly unusual task. Each year, he leads the organisation of an event which almost certainly won't happen.

Wieling is chairman of the Koninklijke Vereniging de Friesche Elf Steden - the Royal Society of the Frisian Eleven Cities.

It is the body responsible for putting on the Eleven Cities Tour, a marathon cross-country skating race over the lakes and waterways of the northern province of Friesland, famed for its intensity.

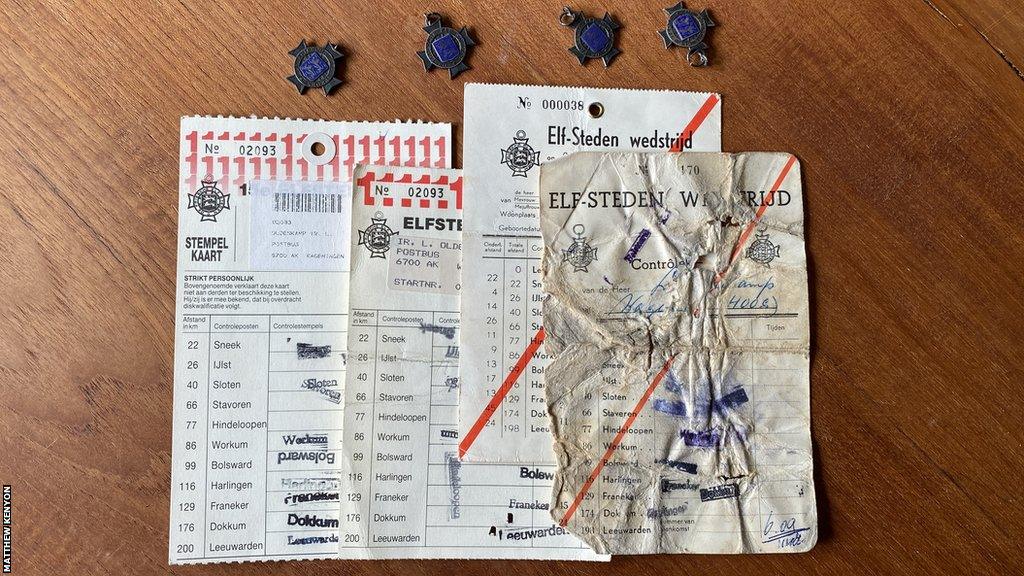

Participants must complete the near-200km course before midnight, getting a card stamped in each town to prove they have passed through.

Wieling and his fellow volunteers do everything that is needed, every year, whatever the weather, to prepare for what would undoubtedly be one of the biggest moments in the Netherlands so far this century.

"Everything, in detail," he says, when asked what level of planning takes place.

"We organise an edition every year. We have a plan consisting of 500 pages or something like that in which every detail has been arranged already on 1 December.

"Because we cannot organise a thing like this in just a few days: we [will] have two million visitors, 25,000 participants, 3,000 journalists, the whole country gets crazy.

"We want to be ready each year in December, so if there is a chance, we can use that chance."

Security, safety, catering, accommodation, traffic management, healthcare - detailed preparations are made, just in case they can go ahead.

But, to state the obvious, it needs to be cold - and the one thing organisers can't prepare is the weather.

"Of course, it's frustrating," says Wieling. "But we know the chance is not that big - if we don't accept that, then we cannot function in a thing like this."

The race needs two weeks of temperatures of around -10C or lower, day and night, ideally without any snow.

That should give a minimum of 15cm of ice around most of the course, enough to bear the weight of 25,000 people in a brief 24-hour window.

The first official race in 1909 was one of only 15 times those requirements have been fulfilled in 124 years.

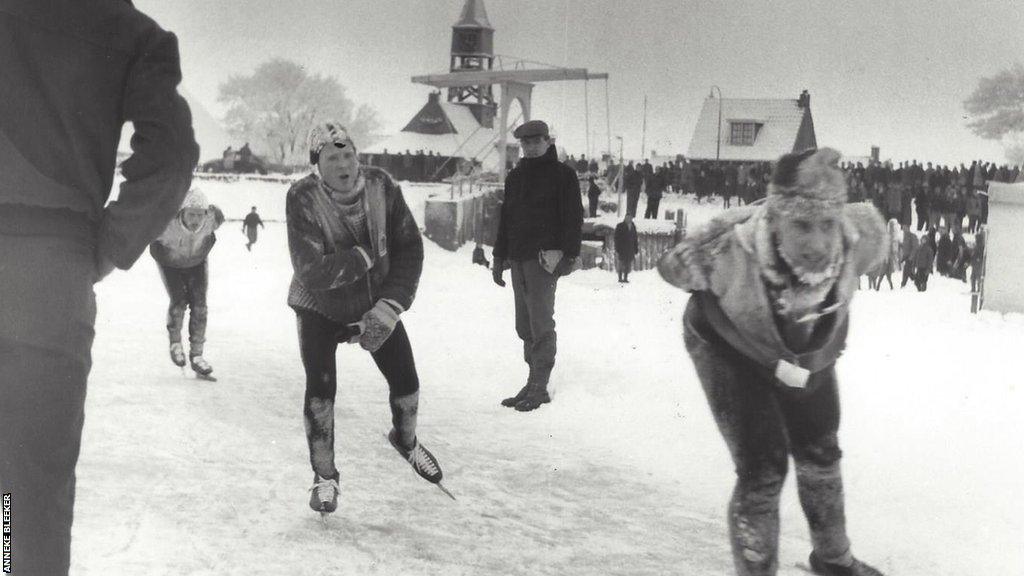

A competitor in the 1963 race arrives in the city of Sneek, clutching the card he needs stamped to prove he has passed every checkpoint on the course

Back in 1963, the field was somewhat smaller, but the conditions were the worst ever known.

Oldenkamp and another 500 or so competitive skaters had set off in the dark, in the early hours.

The near 10,000 'tour' skaters - members of the Royal Society who are enthusiastic amateurs seeking to complete the course rather than win - would follow behind them.

For the serious racers, there was a kind of 'Le Mans' start, with competitors running around a kilometre to the first watercourse, before putting on their skates.

As the crowds and the town faded into the freezing darkness, the challenge truly began for Oldenkamp.

He could, he says, hear his competitors as they set out across the first of the lakes to negotiate, but he couldn't see them.

And skating - even for a hugely experienced racer like Oldenkamp - was tough.

A bitter winter, combining viciously low temperatures, snow and strong easterly or northerly winds had left the waterways of Friesland thoroughly frozen - but the ice was far from smooth.

"You couldn't make the proper movement with skates," Oldenkamp says.

"Sometimes it was a long haul, sometimes it was a short haul, and sometimes you were just walking. [It was] impossible to make a fluent movement on your skates and to use your technique.

"If you see the movies of the Elfstedentocht in 1963, it is almost no skating."

The course makes a great loop of Friesland, initially heading south from Leeuwarden, before tracking to the coast then north to the towns of Harlingen and Dokkum, and back to the provincial capital.

The elite field was already well strung out by the time they reached the coast and Oldenkamp found himself with two companions, urging each other on in solidarity rather than competing against each other.

It was now daylight but that didn't help Oldenkamp spot a weak point in the ice, and he plunged through into the freezing water.

"I didn't see it. I went straight into it," he says.

Astonishingly though, it hardly held him up at all.

"There was almost no interruption. I'm an experienced man in going through the ice. As soon as you are in the ice, in the water, you come out - skate on," he said.

"You have a wet racing suit but there's no problem. You start moving and it's OK. If you stop and try to change clothes, that's the wrong thing to do."

Oldenkamp carried on, but behind him, as the thousands of tour skaters negotiated the early stages of the course, the weather was rapidly worsening.

Oldenkamp (front) was one of only a handful of skaters to make it through the dreadful conditions to the finish line

Only once has Wiebe Wieling come close to announcing that the race would take place.

That was back in 2012, when the Netherlands was briefly gripped by 'Elfstedentocht fever'.

A long period of cold weather left large swathes of the country frozen, but the ice never reached the required thickness in the south of the province.

Instead of triggering all the frenzied last-minute preparations that would be needed, Wieling's eventual task was to disappoint millions.

But he has not given up hope of being able to finally put his plans into action.

"I am getting less confident, because of the things we see round the world in weather and climate changing," he says.

"But we always say here we only need two weeks [of] high pressure in the north of Europe and we can have an edition, and there are exceptions in the weather and climate all over the world.

"So because there is still a small chance, we have to be prepared to use that chance and take advantage of this possibility. So everybody is still working, each year."

Observing the frenzy which greets the onset of cold weather, he is phlegmatic. Frisian locals, he says, are less likely to succumb to over-optimism than their neighbours in the rest of the Netherlands.

"We know what it takes to organise it, so we don't get excited if there's a prediction for one week of ice," Wieling says.

"But the rest of the country already gets hysterical about a period of frost that will lead to people on the ice."

A volunteer measures the ice in 2012 when hopes were raised and then dashed that the race might be staged for the first time since 1997

As Oldenkamp and his companions struggled, the bitter 1963 conditions bit harder. The wind picked up, temperatures fell further, and it became even more difficult to find the route.

Information gleaned in each town - where participants get a stamp on a card to prove they have passed that way - was sketchy.

Oldenkamp thinks he was about 10th and was told that Paping - the leader - was "10 or 20 minutes in front". No-one seemed to know for sure.

At the small settlement of Bartlehiem, where skaters must turn away from their ultimate destination in order to reach the final staging post of Dokkum, someone tried to stop Oldenkamp from continuing.

They told him the weather was too bad and tried to untie his skates. With his frozen fingers, it took him many minutes to retie them. Oldenkamp's chance of winning was long gone, but he never thought of giving up.

"It was horrible, but you must be narrow-minded then. You must have only one purpose. I have to reach Leeuwarden," he says.

Strung out behind him, as the weather worsened and daylight began to fade, were thousands of participants, whose chances of reaching the end in one piece were receding fast.

Battered by strengthening winds, with the course increasingly covered in windblown snow, many had barely made it halfway round.

Oldenkamp poses with the skates in which he competed in the 1963 race

The deepening cold and approaching night carried the threat of chaos and tragedy.

Organisers decided that action needed to be taken and instructions went out to prevent people continuing.

Even then the Elfstedentocht was a rare event, and to be deprived of the chance to finish - effectively forced from the ice - was a bitter blow for many.

But Oldenkamp says the right choice was made.

"It was already dark, it was six o'clock, and the wind was stronger and stronger. I think most of them would never have finished in time and would have got lost, and it was for safety reasons the best thing they could do - take them from the ice."

A film was made about the race a few years ago - it was called 'The Hell of '63'. Of the roughly 500 racers and 10,000 tour skaters, only around 120 completed the course that day.

They were led home by Paping.

Watching film of him being greeted when he returned first to Leeuwarden, you can see the toll it has taken on him.

Snow-blinded and barely able to skate, having raced the second half of the tour entirely on his own, he is obviously close to exhaustion.

He is swamped by the huge crowd - including Queen Juliana and Princess Beatrix - which had gathered to welcome him home.

Some time later, Oldenkamp made his own finish, an hour and 20 minutes after Paping, in 44th place. The royals had gone, but the welcome - and the feeling - was the same.

"There were a lot of people and they help you and they were enthusiastic. I felt as if I had won the race," he says.

"They came with flowers - immediately, when I was at the finish line I got flowers. And I got support, drinks, and 'how do you feel?' and 'let me look at you, come on'.

"I was broken, and I was happy that somebody supported me. I just reached the finish line and then I needed support to do the next… well it wasn't skating; you were moving on skates.

"I was not skating any more. It was impossible to skate!"

Paping was greeted by journalists, fans and royalty as he claimed a famous victory in 1963

Paping's feat in 1963 brought him lasting nationwide fame, which wasn't always welcome.

"His wife always said it has been the most terrible thing in our lives, because he never said no to a journalist, or to an invitation or to an opening," says Wieling.

The back-to-back winner of 1985 and 1986, Evert van Benthem, moved to Canada - in part to escape the constant attention.

Although female skaters had taken part almost since the beginning, 1985 was the first year in which they were officially allowed to compete.

Lenie van der Hoorn was the first female competitor home that year. If and when the Elfstedentocht takes place again, there will be a separate title for women for the first time.

Twenty-seven years and counting since the last edition, it's impossible to predict exactly what impact the next race will have - if it comes at all.

But Wieling is certain the winners will continue to occupy a special place in the Netherlands' sporting pantheon.

"You will be the hero of the country for many years, until you die," he says.

"No-one will ever forget you - and you will be confronted with that every day."

Even in the continuing absence of ice, the lure of the route between Friesland's 'Eleven Cities' remains.

In 2019, former Olympic open-water champion Maarten van der Weijden - who had leukaemia in his youth - raised millions of euros for cancer research when he swam the route.

In 2023 he capped even that remarkable feat with an Eleven Cities Triathlon, completing three laps of the course - one in the water, one on a bicycle and one on foot, accompanied by swelling crowds of supporters and again raising millions.

There is an Eleven Cities cycling tour which takes place each year, while tourists can trace the route at a more leisurely pace.

During the winter, thousands of Dutch skaters head to higher, colder climes to take part in an 'alternative Elfstedentocht', racing the full distance around a lake in Austria.

There is even a musical, launched in October in a specially built theatre in the Frisian capital, which has the Elfstedentocht as its central theme.

A revolving, ice-covered stage allows the actors to skate while remaining stationary in front of the audience.

But it is the real sport, and the original route, which holds the tightest grip on the Dutch imagination.

Every year, when there is a cold snap, they head for the ice.

Sports skaters gliding at high speed through frozen landscapes, families teaching youngsters the magic, young and old gathering wherever there is enough ice to skate.

Freezing weather, hot drinks, sweet snacks - and every year the same excited conversations. Could it happen? Will there finally be an Elfstedentocht this year?

Skaters queue up at the stock exchanges building in Leeuwarden to register for the 1963 race

Leffert Oldenkamp's completed cards and medals from his Elfstedentocht racing career