Q&A: Northern Ireland leaders’ abuse apology

- Published

Survivors of abuse committed over seven decades in state-run and other institutions in Northern Ireland have received a long-awaited apology.

It came from Stormont's political leaders more than a decade after an inquiry was set up to examine a litany of allegations.

BBC News NI outlines what happened and why it has taken so long to get to this point.

Who is the apology for?

The long-awaited apology was recommended following what was at its time the UK's biggest child abuse public inquiry, which reported back in 2017.

The Historical Institutional Abuse (HIA) inquiry examined allegations of abuse in 22 homes and other residential institutions between 1922 and 1995, including those run by the state, local authorities, churches and the children's charity Barnardo's.

It was established to focus on a range of survivors, from those who had suffered alleged sexual abuse to others who had detailed their physical and emotional suffering, as well as issues of neglect and other failings.

Many people told the inquiry they had endured abuse in a number of ways.

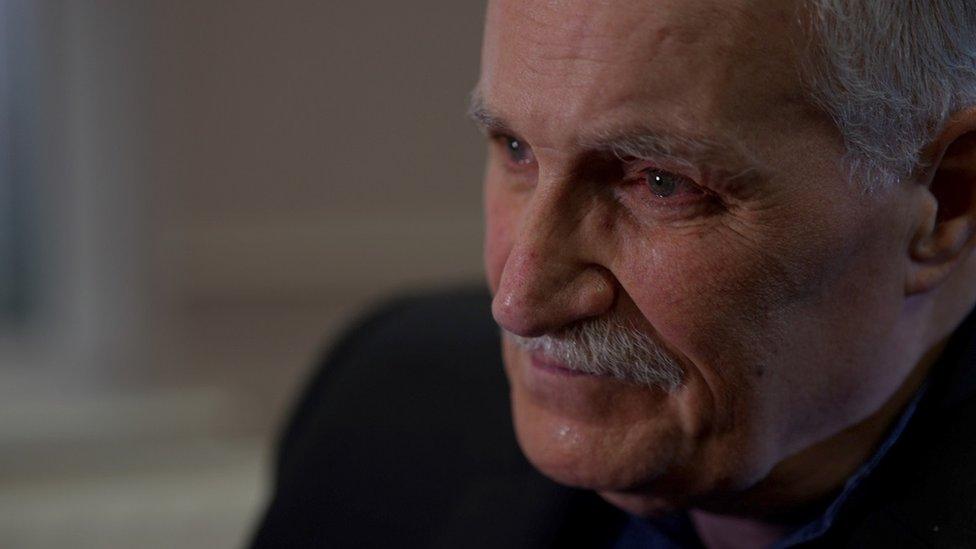

Brian O'Donoghue, who was sexually abused aged nine, said he didn't understand what was happening but that he knew "it was wrong to be touched".

Child abuse survivors have waited for an official apology five years after the HIA inquiry

Kate Walmsley, who was sexually abused between the ages of eight and 12 at an institution in Londonderry, said she still felt "lonely" many years after her ordeal.

"I just never felt I belonged anywhere," she told BBC News NI.

The inquiry heard allegations that abuse was carried out by institution staff members, visitors and even fellow residents.

Many of them told the inquiry and the media that the abuse they suffered had affected their wellbeing and lives in the decades since.

Margaret McGuckin, from the campaign group Survivors and Victims of Institutional Abuse (Savia), said she believes her brother Kevin's learning difficulty is related to the abuse he suffered as a child.

Among those who gave evidence were people who were frail and elderly, recounting the horrors of their past.

When the HIA Inquiry report was published in January 2017, Ms McGuckin highlighted that many abuse survivors had died before the inquiry was set up, while others who gave evidence had not lived to hear an official apology after years of delay.

Many people had suffered a denial of "any form of justice", she said.

What was the HIA Inquiry?

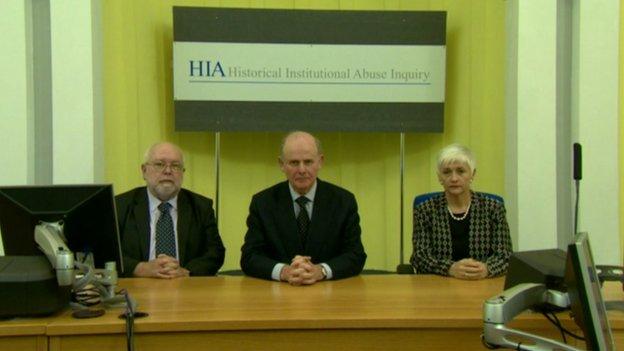

The inquiry was formally set up by the Office of the First and Deputy First Ministers in 2012, and chaired by retired high court judge Sir Anthony Hart.

Its aim was to identify "systemic failings by institutions or the state in their duties towards those children in their care".

During the inquiry, 246 individuals gave evidence in person.

A further 87 statements were read into the record, with some former residents too unwell to attend the hearings.

Sir Anthony Hart chaired the HIA inquiry

With a scheduled publication date of January 2016, the inquiry's final report was delayed by a year with the agreement of the Northern Ireland Assembly.

This led some campaigners to call for an interim report and for compensation payments to begin before the inquiry had concluded.

However, the final report was eventually published in January 2017.

What did the HIA Inquiry find?

Sir Anthony, who died in 2019, concluded there was widespread abuse and mistreatment of young residents at the institutions under investigation.

The largest number of complaints heard by the inquiry related to four Sisters of Nazareth homes, where nuns had physically and emotionally abused children in their care.

In his report, external, Sir Anthony reflected on the context of the Troubles and that for many years "the financial circumstances and living conditions were very poor" in Northern Ireland's institutional homes.

The abuse of children at Kincora Boys' Home was examined during the inquiry

At Kincora Boys' Home in east Belfast, 39 boys "were abused at some point during their time" in the home, the report concluded.

It found that a 1974 police investigation into one convicted abuser, William McGrath, was "inept and inadequate".

The report also highlighted there was a failure to take action by the Norbertine Order against the priest Brendan Smyth, who was eventually convicted of dozens of offences against children over a 40-year period.

Among its many findings, the inquiry also examined claims of abuse by people who were sent to Australia from Northern Ireland as children.

The report noted that while the inquiry mainly focused on failings there were many staff members and volunteers at institutions who "devoted their entire religious or professional lives to the children in their care".

What did the institutions say?

The Sisters of Nazareth apologised to "anyone who has suffered abuse whether psychological, physical, sexual or neglect on any occasion when the sisters' standard of care fell below what was expected of them".

Archbishop Eamon Martin, the head of the Catholic Church in Ireland, added that there had been "an appalling betrayal of a sacred trust" experienced by those who were abused in religious institutions.

Archbishop Eamon Martin said there should be reparation and outreach for victims

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) and the Health and Social Care Board also issued statements to acknowledge their failings.

Many other institutions and organisations issued apologies, such as the Irish Norbertines who recognised the "tragic harm and hurt caused to innocent children by Brendan Smyth".

What did the HIA report say should happen next?

Sir Anthony recommended that all survivors should receive a tax-free lump sum payment, including survivors of homes and institutions that were not covered by the inquiry, ranging from between £7,500 and £100,000.

Sir Anthony recommend a government-funded compensation scheme for victims

At the publication of the report in 2017, he said 12 people had given evidence at the inquiry and had since died. He concluded it was "just and humane" for their spouses or children to receive a percentage of the money.

He also suggested that a permanent memorial should be established at Stormont and a commissioner for survivors of institutional abuse be appointed.

He further recommended that an official apology be made to abuse survivors.

Why has the apology taken so long?

For much of the report's existence the Stormont Executive has been in turmoil, causing delays to the introduction of redress measures and the official apology.

Sir Anthony's report was published four days after the Stormont government collapsed, on 16 January 2017 - it took three years for the devolved government to be restored.

Campaigners have been calling for the report's recommendations to be implemented in full

In November 2019, Westminster passed the Historical Institutional Abuse Act, which provided the legal framework for the redress scheme to be enacted.

The Historical Institutional Abuse Redress Board started its work to receive and process compensation in March 2020.

With the executive having been re-established in January 2020, Fiona Ryan was appointed as Northern Ireland's first permanent commissioner for victims of institutional childhood abuse in October that year.

In January 2022, a date for the official apology, to be made by Northern Ireland's first and deputy first ministers, was set - 11 March.

However, this was cast into doubt when the executive collapsed with the resignation of Paul Givan as first minister.

In February, it was agreed that ministers representing the five main parties - Michelle McIlveen (Democratic Unionist Party), Conor Murphy (Sinn Féin), Nichola Mallon (Social Democratic and Labour Party), Robin Swann (Ulster Unionist Party), and Naomi Long (Alliance) - would deliver a statement.

As of yet, there has been no decision made on the establishment of a permanent memorial to those who suffered from institutional abuse.

How did the HIA report compare to similar reports?

The HIA Inquiry followed the publication of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse, external in the Republic of Ireland, which was published in 2009.

It examined allegations of abuse at Catholic-run institutions over a 60-year period.

The inquiry found church leaders knew about "endemic" levels of sexual abuse taking place in institutions for boys.

It also reported that many children lived in a "climate of fear" and some experienced a "daily terror of not knowing where the next beating was coming from".

After this report, survivors of institutional abuse in Northern Ireland started a petition for Stormont to begin a similar inquiry.

In England and Wales, the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) has been examining claims against local authorities, religious organisations, the armed forces and public and private institutions, as well as figures in the public eye since 2015.

Its last public hearing was in December 2020, with a final report to be published later in 2022.

- Published11 March 2022

- Published11 March 2022

- Published20 January 2017

- Published9 July 2019

- Published14 February 2022

- Published20 January 2022

- Published20 January 2017

- Published11 December 2020

- Published3 February 2015