New clue to anti-matter mystery

- Published

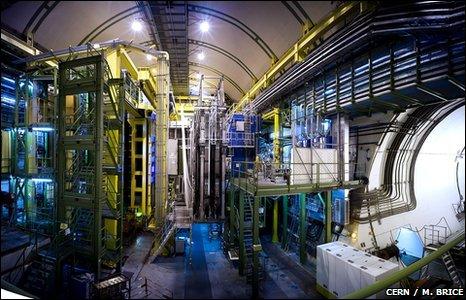

The team observed collisions in the Tevatron accelerator

A US-based physics experiment has found a clue as to why the world around us is composed of normal matter and not its shadowy opposite: anti-matter.

Anti-matter is rare today; it can be produced in "atom smashers", in nuclear reactions or by cosmic rays.

But physicists think the Big Bang should have produced equal amounts of matter and its opposite.

New results from the DZero experiment at Fermilab in Illinois provide a clue to what happened to all the anti-matter.

This is regarded by many researchers as one of the biggest mysteries in cosmology.

The data even offer hints of new physics beyond what can be explained by current theories.

For each basic particle of matter, there exists an anti-particle with the same mass but the opposite electric charge.

For example, the negatively charged electron has a positively charged anti-particle called the positron.

But when a particle and its anti-particle collide, they are "annihilated" in a flash of energy, yielding new particles and anti-particles.

Similar processes occurring at the beginning of the Universe should have left us with equal amounts of matter and anti-matter.

Yet, paradoxically, today we live in a Universe made up overwhelmingly of matter.

Unexplained result

Researchers working on the DZero experiment observed collisions of protons and anti-protons in Fermilab's Tevatron particle accelerator.

They found that these collisions produced pairs of matter particles slightly more often than they yielded anti-matter particles.

The results show a 1% difference in the production of pairs of muon (matter) particles and pairs of anti-muons (anti-matter particles) in these high-energy collisions.

"Many of us felt goose bumps when we saw the result," said Stefan Soldner-Rembold, one of the spokespeople for DZero.

"We knew we were seeing something beyond what we have seen before and beyond what current theories can explain."

Dr Guennadi Borissov, from Lancaster University in the UK, who is co-leader of the project, said: "This beautiful result provides important input to understanding the matter dominance in the Universe.

"The DZero experiment is still collecting data and so, as long as funding for our work continues, we can expect to make even more precise measurements of this effect in the future."

The dominance of matter in the Universe is possible only if there are differences in the behaviour of particles and anti-particles.

LHCb was designed to shed light on the anti-matter puzzle

Physicists had already seen such differences - known as called "CP violation". But these known differences are much too small to explain why the Universe appears to prefer matter over anti-matter.

Indeed, these previous observations were fully consistent with the current theory, known as the Standard Model. This is the framework drawn up in the 1970s to explain the interactions of sub-atomic particles.

Researchers say the new findings, submitted for publication in the journal Physical Review D, show much more significant "asymmetry" of matter and anti-matter - beyond what can be explained by the Standard Model.

If the results are confirmed by other experiments, such as the Collider Detector (CDF) at Fermilab, the effect seen by the DZero team could move researchers along in their efforts to understand the dominance of matter in today's Universe.

The data presage results expected from another experiment, called LHCb, which is based at the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva.

LHCb was specifically designed to shed light on this central question in particle physics.

Commenting on the latest findings, Dr Tara Shears, a particle physicist at the University of Liverpool who works on LHCb and CDF, said: "It's not yet at the stage of a discovery or an explanation, but it is a very tantalising hint of what might be."

Dr Shears, who is not a member of the DZero team, added: "It certainly means that LHCb will be eager to look for the same effect, to confirm whether it exists and if it does, to make a more precise measurement."