Young, Kurdish, and jailed in Turkey

- Published

Hundreds of children in Turkey's Kurdish south-east have been jailed for taking part in anti-government protests, and are treated no differently from adults.

Berivan Sayaca, 15, is held at a high-security prison in Diyarbakir

Berivan Sayaca is an attractive, 15-year-old Kurdish girl with black, wavy hair who loves horse-riding and playing the guitar.

She is also a convicted terrorist - serving an eight-year sentence in the high-security prison in Diyarbakir, the largest Kurdish city in Turkey. How she got there is a tale that could be straight out of Kafka, that exposes one of modern Turkey's darkest sides.

The Turkish armed forces have been fighting insurgents of the PKK, or Kurdish Workers Party, for more than a quarter of a century.

The PKK is considered a terrorist group, not just by Turkey but by the US and the EU.

More than 40,000 people are believed to have died in the conflict, on both sides.

At the height of the conflict, in the early 1990s, hundreds of Kurdish villages were destroyed by the Turkish army.

The inhabitants of those villages, and other displaced by the conflict, moved to places like Batman, a bleak city of dull concrete apartment blocks, surrounded by the featureless fields of the eastern Anatolian plateau.

Berivan Sayaca's family moved there in the late 1980s. But her father then moved the family to Istanbul in search of work. He worked as a construction labourer.

Mariam Sayaca travels every week to see her daughter in prison

Berivan Sayaca had to leave school and go to work in a factory at the age of 10. The family went back to Batman to stay with relatives last October.

On Friday 9 October, 2009, she went out to visit her aunt. She never came back.

Adult prison

The next the family heard was that she had been arrested by the police for taking part in a demonstration. These occur frequently in the overcrowded cities of the south-east.

Hostility towards the Turkish state runs very high in Kurdish communities, and people of all ages come out to protest, often throwing stones, and occasionally petrol bombs, at riot police, who respond in kind with tear gas and water cannon.

The only evidence police produced at Berivan Sayaca's trial four months later was a photograph of her, a scarf pulled across her face, apparently at the protest. She denies being part of it, or throwing stones.

But under Turkey's severe criminal code, that was enough to convict her of supporting a terrorist organisation.

More than 350 children between the ages of 13 and 17 are now serving sentences in adult prisons in Turkey on similar charges.

"It's not up to the judges, it's a question of the system," says defence lawyer Serkan Akbas.

He explained that in the eyes of the law, by attending a demonstration called by the PKK, a person is automatically treated as a PKK member.

All Kurdish protests are presumed by the state to be organised by the PKK. And membership of the PKK is a terrorist offence. Under the penal code terrorism offences apply even to young teenagers.

Mr Akbas says there is little scope to defend youngsters like Berivan Sayaca, nor can judges give less than the minimum sentences mandated by law - if they did they would almost certainly be reinstated on appeal.

"I don't feel like there's a trial going on," he says.

"I feel like there's a war going on, and these children, for protesting against the Turkish state, are being punished for being on one side."

Berivan's mother Mariam Sayaca is now staying in Batman, so she can make the two-hour journey every Monday morning to Diyarbakir for the half-hour meetings she is allowed with her daughter.

She says Berivan cries all the time, and begs to be freed. Neither of them can understand why she is there, in an adult prison surrounded by hardened criminals and PKK militants.

'Political will'

Finding officials to justify this practice is difficult.

Neither the police, the judges, nor the prosecutors involved in applying terrorist charges to children would talk to the BBC about it. They simply said they were bound by the law.

So what about the government? The governing party, the AKP, has promised a new beginning for the Kurdish minority, talking of a softer, more tolerant approach.

But it was the AKP which passed the severe anti-terrorism law five years ago.

"When we passed it there was a lot of unrest, with 17-year-olds throwing petrol bombs," says Justice Minister Sadullah Ergin.

"The law was intended to deal with them - but obviously it is wrong that it now catches much younger children who are only throwing stones."

But there is little sense of urgency among the politicians. The AKP accuses the opposition parties of blocking its efforts to change the law.

The opposition says that with its majority in parliament the government could easily pass a new law if it wanted to.

This lack of political will betrays the acute sensitivity of all politicians to nationalist sentiment in Turkey, which is easily whipped up and sometimes violent.

Soldiers are still killed by the PKK - several dozen every year. They are always called "martyrs", and every PKK insurgent a "terrorist".

Failing to adhere to this official nomenclature is a crime. One Kurdish newspaper editor was jailed for 166 years this month for writing and activity judged to be supportive of the PKK.

A government minister had his nose broken at a soldier's funeral last month by a nationalist infuriated by what he saw as the government's soft line towards the Kurds.

'State of mind'

"Turkish society has a kind of paranoia about disintegration, secession," says Ergun Ozbudun, one of the country's most renowned legal scholars, who has long pushed for reform of the military-drafted constitution.

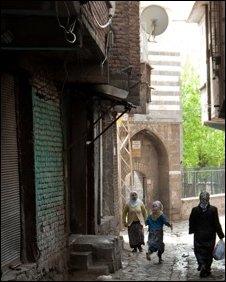

Anti-government feeling runs high in Turkey's Kurdish areas

"In the minds of many Turks a strong state, with a strong hand, is a must. In Europe and elsewhere in the Western world, the judiciary is primarily the protector and guarantor of individual rights and liberties.

"Here the picture is reversed, the judiciary is the protector and guarantor of the official ideology and the dominance of the state."

Poor and unschooled in the Byzantine ways of Turkey's judiciary, Mariam Sayaca has no idea how to go about campaigning for her daughter's release.

Nor how she can keep up the weekly visits to jail, with the family now split between their home in Istanbul and the house of their relatives in Batman.

"What if it was the prime minister's daughter?" she asks, clutching a photograph of her child.

"Could his wife sleep at night? Would she accept this situation?"

- Published20 May 2010