Tech Know: A journey into sound

- Published

The BBC Technology index has been writing about makers, hackers and other assorted tinkerers for over a year. Time, then, to see if any of the skills and crafts we have filmed and written about have rubbed off.

All we needed was a project.

As if on cue, an e-mail fell into the inbox from Allegra Hawksmoor who told us about a band called The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing. One track of their next album, called Now That's What I Call Steampunk - Volume One, will be available on a wax cylinder. The CD album and single wax cylinder track will be available from 1 June.

"As far as we're aware, it's the first album to be sold with (at least a partial) wax cylinder release for the best part of a century," she said.

Anyone buying one of the 40 copies of the track on wax will also get instructions for building a phonograph to play the cylinder.

Would we be interested in finding out more, she asked?

Getting the phonograph to work proved tricky

Yes, we said, we would. Just try stopping us.

The idea to put one track on a wax cylinder came from band member Andy Heintz.

"The second I heard him say it, I knew we had to do it," said Ms Hawksmoor. However, she added, she had no idea whether it was even possible.

The internet helped Ms Hawksmoor find Adrian Tuddenham of Poppy Records, one of the few souls in the land that can put digital recordings onto wax cylinders.

Finding Mr Tuddenham solved one problem. The other, bigger, task was to draw up plans for a home-brew phonograph that would cost about £20 to make.

But she already knew someone who could help with that.

Professor Offlogic, aka Sam Kimery, is a veteran maker. "Making things has always been a necessity for me," he told the BBC.

"Nobody made good Star Trek props, or toy Geiger counters or any of the neat stuff I wanted to play with," he said. "This led, naturally, to blowing stuff up with a chemistry set, which led to electricity (hey, some of those exploding things needed a remote trigger) and general inventing and tinkering with things."

He adds: "If you don't want what everyone else wants you have to make your own, the market just doesn't serve you very well if you are at all strange."

This led him to a career in hi-tech and a lifelong interest in making stuff. As a result creating a phonograph from scratch was no stretch, even though he had never actually done it before.

"I remember playing an Andy Williams LP using a paper cone and sewing needle as a kid," he said. "That's about as close as I got to this project before."

The Prof sent along the plans and we set about getting all the parts together. We scoured DIY shops, craft stores, hobby shops and the cookery aisles of lots of supermarkets. Some bits were easier to find than others. Inspiration struck when we found a cone-shaped metal measuring jug that became our sound horn.

The internet helped with other parts, particularly the little motors and pulleys needed to get the cylinder turning.

Once we had the bits piled up, the work started. At that point we handed over to Jason Palmer who, as a doctor of physical chemistry, has far more experience with building stuff than anyone else. He takes up the story.

Tinker time

It is the simplest mechanical means to record and reproduce sound - hence the rich history stretching back to one of history's great inventors.

But how about making one, today, with bits you can easily get your hands on? In principle, it's easy, but we were provided nothing more than a schematic with no dimensions, so some careful planning and improvisation were both required through the day.

We had our greatest trouble getting a smooth movement of the cylinder.

Partly that was down to getting the O-ringed motor shaft centred and stable between the rails on which the cylinder sat. But more than that, the trouble was the sliding friction against those rails.

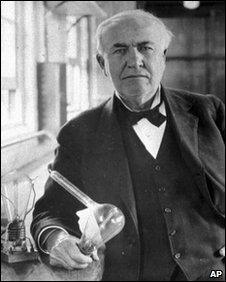

Thomas Edison, inventor of the phonograph and patron saint of many a maker.

From a design point of view, there are no constraints on these, so take the time to find the right rails and ideally some bearings that they can turn in, or bearings that fit on the rails themselves and can be fitted with O-rings.

Our attempts with O-ringed plastic wheels and then with plain rubber grommets were woefully inadequate to keep the cylinder from bouncing all over the shop.

One thing to keep in mind throughout is the tiny size of your signal.

Even if mechanically everything turns and moves as it should, the phonograph needs to carry a minuscule vibration from the stylus through to a resonator and then out a tube and into a horn.

Every connection is another place where sound can effectively be lost, so aim for the shortest path between needle and ear, trying to mechanically isolate anything that's carrying sound.

Our first stylus, a carefully cut section of aluminium can, served more to scratch the cylinder than play anything from it; in the end we fitted the player with a length of wire that did the job far better.

Sound lessons

So, we did it and got it working, after a fashion. Even if it took Poppy Records to help refine the design and improve the sound output.

But as has often been said of anything that is hand-made, be it a work of art, a tiled bathroom or a phonograph built from bits; these things are never finished, they are more or less abandoned.

Why? Because you know the corners that were cut when the work was being done; the unfinished parts that are obvious to you and no-one else; and all those ideas you had about improving it while making it are clamouring for attention. Even if it works, and works well, you know it could work better.

Despite that, there is comfort in knowing that being a hacker or a maker is a journey not a destination, and that no matter how high the shoulders you stand on, you'll never see over the horizon. It is consoling to realise that you, at least, have raised your eyes to the sky and are looking in the right direction.