'I'm a walking artefact' of Bloody Sunday

- Published

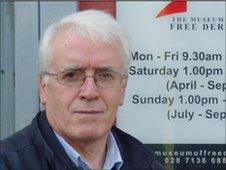

John Kelly's brother was shot dead on Bloody Sunday

"I'm the brother of Michael Kelly, who was murdered on Bloody Sunday".

That's how John Kelly introduces himself to everyone who comes to visit Free Derry Museum.

"Then there's that moment when their eyes pop".

"People are surprised I'm prepared to talk about it."

Now the Education and Outreach Officer at the Bogside museum, he was 23 when his 17-year-old brother was shot dead along with 12 others when the British parachute regiment opened fire on a civil rights march.

Each year Bloody Sunday brings thousands of people into the area, to visit the museum and the memorial to the victims, and see for themselves where the events of 30 January 1972 took place.

For John it is an opportunity to tell the truth about what happened that day.

"I'm a walking artefact, but I see myself as speaking on behalf of Michael.

"I was there, I witnessed it, I was there when he was placed in an ambulance and I was there in Casualty and I was there when he was pronounced dead and I was there in the mortuary with ten other bodies.

"That's what makes the job worthwhile, being able to tell people what happened," he said.

The museum's exhibits include the famous handkerchief waved by Father Daly on Bloody Sunday

His visitors have included everyone from Basque separatists and Palestinians to loyalist ex-prisoners and former RUC officers and, once, an ex-Paratrooper.

"I knew immediately he was too young to have been here on Bloody Sunday, but when I heard he was an ex-Para, my heart did thump.

"At one time he did security for Bono, which is how he learnt what happened.

"He said to me, 'What they did was wrong', and apologised.

"The English often apologise when they come here, but I always say they haven't done anything wrong.

"The only people I have an argument with are the British government and the British army.

"We're here to educate. There's no bitterness. I'm here to help tell the story, and if people believe it or don't believe it, that's up to them," he said.

As co-ordinator of Free Derry Tours and tourism co-ordinator with the Gasyard Trust, Mickey Cooper spends many of his days showing visitors where Bloody Sunday happened.

He freely acknowledges that the events of 30 January 1972 are "the driving force" behind tourism in the area, but believes it is better that local residents tell the story themselves.

"People can go up on the city's walls and look down and the murals and maybe take a few photographs and have no economic impact on the area, or they can come down into the Bogside and spend time here.

"Because of censorship and the atmosphere during the Troubles, it was difficult for people in the Bogside to make themselves and their story heard.

"People here just want to tell their story properly and accurately, so we encourage people to come into the area.

"It's educational, but its also economic, because if they come here and spend money they will help develop the economy in the Bogside.

"It's not about making money through people dying.

"The interest is already there, so the question is whether we want people simply looking down from the walls, or do we want them coming into the area and spending time here and learning about what happened."