Sting in the tail of farming revolution

- Published

Dr Spencer Wells is a geneticist, anthropologist and explorer-in-residence at the National Geographic Society.

In a new book, Pandora's Seed, he charts the unforeseen costs of farming, which began to transform society 10,000 years ago, but brought with it illnesses such as diabetes and obesity.

BBC science reporter Paul Rincon met Dr Wells to find out what lessons we could learn from the past and what might lie in store for our species over the next 10,000 years.

The majority of the world's population now depends on farming

PR: Could you briefly summarise the main themes of your book?

SW: In the book, I talk about global warming and overpopulation. I trace a lot of these issues back in time to the dawn of the Neolithic. This was a period when humanity made a sea change in its culture. We settled down and started growing our own food.

Given that it has been so successful - 99.99% of the people in the world today are agriculturalists, and hunter-gatherers are a tiny minority - you would guess that it is successful for a reason. That it is a wonderful way of life, improved our health and so on.

It turns out, that's not actually the case. Even if you look at very early communities, as they made the transition from a hunting and gathering lifestyle to farming in the same region, they became less healthy. They ended up shorter, they tended to die younger, the skeletal structure changed in a way that's consistent with a decreased level of nutrition. So the question is why did (farming) win out?

Dr Wells claims that humankind has reached a crossroads

It turns out the reason we became agriculturalists is that we were backed into a corner - a climatological corner. At the end of the last Ice Age, things were warming up, population densities at some locations increased significantly. And some people started to settle down.

Then as things continued to warm up, this ice dam in North America melted, letting loose the deluge of Lake Agassiz (a huge glacial lake in North America which drained around 13,000 years ago), killing the Gulf Stream which had served to warm up western Eurasia for the last few thousand years.

Basically, we were plunged back into Ice Age-like conditions during the Younger Dryas (12,800-11,500 years ago). Carrying capacity had not kept up - we had too many people moving on the land at the time, and they couldn't support themselves as hunter-gatherers so they had to develop an innovation. And that innovation was agriculture. It made total sense at the time, as a reaction to an extreme climatic shift - a crisis.

But unfortunately, it had lots of ancillary baggage. And the book is really about tracing that ancillary baggage.

We also talk about when we make these decisions, based on proximal stimuli, we need to be thinking longer term. In the final chapters of the book, I talk about what some of these decisions facing us today might be: the applications of genetic technology, how we're dealing with climate change and finding a mythos for the modern age that's perhaps more inclusive than the mythos we have today.

So I talk about the rise of fundamentalism in the 20th Century as a reaction against some of the things which have gone on in the modern world.

PR: So what in your view are the main costs of the Neolithic revolution?

SW: Diabetes, obesity, mental illness, climate change. I talk a little in the book about genetic engineering - re-engineering ourselves and eugenics. It's the fact that we now have the tools to choose the genes for the next generation. People will start to make decisions on that basis - what they want their children to look like genetically.

There is a company in California that early last year announced that it was going to test not only for medically relevant conditions but also hair colour, eye colour and genes which pre-dispose to lower or higher IQ. It's a can of worms that people have been talking about - but the future is happening now.

In a chapter of the book, I talk about Charlie Whitaker, a little boy who was born with a disorder known as Diamond Blackfan Anaemia. It's extremely rare - only a couple of dozen cases every given year in the UK. He had a lifetime of blood transfusions - his body didn't make red blood cells properly.

The only way to treat it or to cure it is to give them a bone marrow transplant or a cord blood transplant from someone who matches. But the bone marrow registries won't do that in the case of this illness. They will only do that for terminal leukaemias and so on because the chance of success for an unrelated donor is only about 15%.

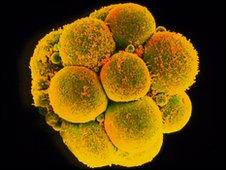

Is genetic screening in embryos the thin end of the wedge?

But the chances with a sibling (match) rise to about 85%. So you can try to have another child that might be a match - but the chances of a match are 25%. Unfortunately, the Whitakers' daughter wasn't a match.

They said, we can go and test for this using pre-implantation genetic diagnosis. We create a panel of embryos, choose the ones that are matches, implant a couple. But the UK authorities said no - that they were creating a donor baby.

This opens up the possibility of testing for these other traits. In the book, I sketch a scenario. The average age of first birth for mothers in the developed world is increasing every year, so it was a little over 21 years old in the 1970s in the US. It's over 25 years now in the US. It's nearly 30 in some countries in Europe, such as Switzerland. For well-educated people it's often higher than that.

Many women are choosing to have IVF now, because they are getting pregnant at 35, 36, or in their 40s. That's a huge investment.

So if you had a way to snap the odds in your favour - if you knew if you could avoid giving them an APOE variant (a protein gene, variants of which are implicated in a number of illnesses, including Alzheimer's disease) - would you choose to take that out of the embryo? I think many people probably would, and surveys tend to confirm things like that. I think we are creating an environment where these technologies are going to be applied routinely in some strata of society. And the question is: Are we choosing the right genes?

I talk about a study that was done on jazz musicians in the "bebop" period and was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry. During what was arguably the most important period, over 80% had serious mental disorders: manic depression, schizophrenia, alcoholism... Some of these had some genetic component, and the question is: Would you choose to remove these?

We live in an age of caloric excess, but will that last?

If you do, how much of that creative spark are you removing at the same time? That's the knife edge we're walking on.

PR: Then, do you think genetic engineering of humans is inevitable? Are we now into management rather than prevention?

SW: I think it is inevitable. I think it is something we have always done. I liken it to those simple decisions about growing crops and manipulating the genes of the crops to make them more efficient - produce more calories - that was done during the Neolithic.

PR: What does it mean to be well adapted to your environment today? Does that have any meaning?

SW: There is a quote that I use at the beginning of the chapter on climate change. It's attributed to Darwin, though no one is really sure that he said it: "It's not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one that's most adaptable to change".

The idea is: we don't know a priori what we're going to need in our back pockets for the future. And I think, deciding at this point in history what we can leave aside could be very dangerous. It's very difficult to say what being well adapted means in this era. We should leave our options open.

It's the same danger we had with developing agriculture. We do something for what seems like a very good reason at the time. But there is this ancillary long-term baggage that comes along with it.

For instance, we live in an era of caloric excess. And suppose we want our kids to be favoured with genes that allow them to metabolise very efficiently. So they burn off all these calories - they can eat 10,000 calories a day and still be skinny, like a supermodel.

That's fine. But what if there is a food crisis in the future - as we are tending towards a global monoculture. What if we have another "potato famine" and there is a restriction in calories. What's going to happen to those kids - are they well adapted anymore? Obviously not.

PR: And what if that happened? How would people in western societies fare now if we had to be more like hunter-gatherers again?

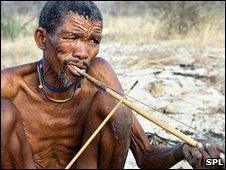

SW: I think we'd be in trouble (laughs). I think I'm probably romanticising hunter-gatherers somewhat in the book. But I have spent time with these groups and there is this remarkable sense of calm and almost coming home after a few days.

And it's because they utilise so much of what it is to be human. So many different parts of the brain - their natural history knowledge is extraordinary.

Then there are the tracking skills, the hunting skills, the gathering skills, knowing where to find things at particular times of year. Even though it looks like a desert, you know where to dig down and find a tuber that's going to keep you alive for a few more days.

Few peoples follow a hunting lifestyle today

We've lost all of that, and I think we've lost a lot in the process. We live in a very technological world, where everything's available to us on Google. But if we lost that ability to Google things and we had to go out and subsist for ourselves in a marginal environment, I don't know that we'd be able to do it. Once you lose it, it's very difficult to get it back.

The Genographic Project (of which Dr Wells is director) has a legacy fund to help preserve this cultural diversity - it's part of what makes us human. I'm not advocating that everyone goes back to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. But I think we should preserve this knowledge, allow the people who want to live in this way to go on doing so and respect them.

Simply because they are not growing crops, because they are not raising livestock, don't have a formalised government or a formalised religion, it doesn't mean they are primitive. It's just an adaptation to the environment they live in.

PR: On what trajectory do you think we are headed as a species? For example, can we sustain continued population growth into the near future?

SW: The UN predicts that we're not going to have as many people as they would have predicted 20 years ago by the middle of this century. It's probably going to stop around 9.2-9.5 billion. After that plateau I suspect it's going to drop off.

The same way it's happening in Japan and some European countries. It's part of the cycle of development. So you go from subsistence to middle class, and then women become better educated and choose to have fewer children. Then the population really starts to drop off. This is a shift which I think is going to happen to our entire species this century.

All of these things are coming to a head now: this is an extraordinary time to be alive. We're dealing with climate change and we're dealing with all these other effects. But also we're also dealing with this tremendous demographic shift, this huge inflection point unlike any our species has encountered since the near-extinction event 70,000 years ago.

We went through that last inflection point, and suddenly we're doing it again in the opposite direction. That alone is going to cause significant changes in human society. The main one is that we can't rely on extracting additional resources and growing our way out of it. We have to become more intelligent about how we utilise those resources?

PR: Do you think that's a realistic goal for humans?

SW: I think it has to happen or we will end up destroying ourselves and the planet. The planet will come back - the cockroaches will survive. But the reason I call the book Pandora's Seed is that Pandora unleashed all these plagues for humanity, but she saved hope in the box.

And I think there is hope. Through all the crisis points in human history we have shown that we are capable of change. And I think we are capable of change now; we just have to see that there are real costs to what we're doing. Then we will be forced into action.

PR: The book focuses on the changes which came with the shift to agriculture; but are there other, potentially game-changing, technologies which have the potential to transform human society?

SW: Genetic engineering is a major one. Engineering crops that grow in high salt conditions or need less fresh water is obviously a major issue for the future.

Most of the big agrotechnology companies have chosen not to focus on that until very recently. They have chosen to focus on creating herbicide-resistant (crops). It's a great business model, but not necessarily good for humanity as a whole.

But I think technologies like that will have to be applied in future. Alternative energy - solar might be the ultimate solution, but I think nuclear options should also be examined. The modern pebble-bed reactors are safer, and cheaper to build.

Dr Spencer Wells is explorer-in-residence at the National Geographic Society and director of the Genographic Project. The themes explored in this interview are expanded in his book Pandora's Seed: The Unforeseen Cost of Civilization. He is a Rhodes professor at Cornell University in Ithaca, US.