Russia's drive to improve its image

- Published

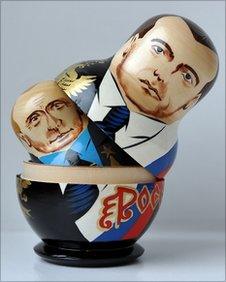

Russia, unhappy with its image abroad, has taken a fresh public relations approach to present a better view of itself and attract foreign investment.

Russia's image is damaged by both historical and recent factors

One example is the Russian National Exhibition in Paris, organised by Russia's Ministry of Industry and Trade and being opened by the country's Prime Minister Vladimir Putin.

It's another attempt by Moscow to tell what it sees as the real story, different from what some Russian commentators call an excessively negative coverage of Russia in Western media.

In recent years, Russia has launched international English and Arabic news channels, hosted international economic forums and discussion clubs, started funding supplements in foreign newspapers and even hired some Western PR companies.

Large international PR agency Ketchum was hired to help Russia "shift global views" of the country prior to and during the 2006 G8 summit.

It said afterwards that the main aim had been "to ensure that Russia's openness, accessibility and transparency were widely communicated to participants and observers of the summit and to the media".

The Kremlin's greater openness during that summit, and its dignified response to the recent tragedy of the Polish presidential plane crash, certainly sent positive signals abroad.

But experts agree that it will require much more to change Russia's image than a number of PR moves, no matter how good and expensive.

"It takes generations for a country's international standing to change, and countries need a great deal of patience if they are serious about such things," policy adviser Simon Anholt told the BBC.

Conflict-related

Dmitry Gavra, Russian political expert and professor at the Saint Petersburg State University, believes that Russia's image has been damaged by both historical "negative constants" and some recent developments.

He highlights "image mistakes" made by Russian officials, a lack of institutional and structural reforms in the country and Russia's recent attempts to return to the system of global competition in geopolitics, technology and economy as the new factors.

They have been combined with the usual perceptions of Russia as a country with an anti-Western attitude, always eager to expand and position itself as a missionary in dealings with its neighbours and the rest of the world.

For example, gas rows with Ukraine and Belarus, seen by most Russians as purely economic disputes, were criticised by some Western opponents as Russia's attempts to use its energy superpower status as a geopolitical weapon.

Mr Anholt says that one of the main problems for Russia is a very low number of "informal ambassadors" around the world, such as famous consumer brands or international media personalities that people like and associate with Russia. The country also does not have a big tourism profile.

"Russia's business and political figures usually seem to acquire their international profile for negative reasons," says Mr Anholt.

"The only international media stories about Russia generally relate to conflict or instability."

Internal view

Mr Gavra also points out that it is impossible to separate internal and external images of Russia.

Bureaucracy, corruption, the huge gap in earnings between wealthy and poor Russians, the low prestige of state institutions, relations between the police and the people - all these factors create a negative image of the country, even among many Russians.

"Of those Russians who spend their holiday abroad, some do not even want to admit they are from Russia and try to speak foreign languages," he says.

In turn, Mr Anholt believes that Russia does not come over as being very well disposed to outsiders.

"The truth may well be rather different, but perception, unfortunately, always trumps reality," he says.

Positive moves

Experts agree that only big changes in Russian policy and in its dealings with the rest of the world could gradually improve the country's image.

The question is, though, whether Moscow is ready to implement these long-term changes and will not abandon them if the internal situation changes.

The Kremlin's rhetoric for most of the 2000s alerted many in the West, who considered it hawkish and unfriendly towards private business.

But Mr Gavra believes that "for many Russian officials, those things are right which are effective".

It was effective back then to be seen as tough, he says, but the situation has changed.

"We already see important changes in the areas which matter to Russia's Western partners," says Mr Gavra.

They include the new anti-corruption drive, new ways of dealing with suspected corruption and the rise of the internet.

This has brought about a kind of "electronic democracy", in which entrepreneurs can do much of their business online, avoiding queues and not having to deal with corrupt bureaucrats.

"These things will be better for Russia's image than 10 economic forums," says Mr Gavra.

As Mr Anholt puts it: "'What can Russia say to make itself liked?' is simply the wrong question.

"The only meaningful question is: 'What can Russia do to make itself relevant?'"