Baghdad diary: Saddam's sculptor makes comeback

- Published

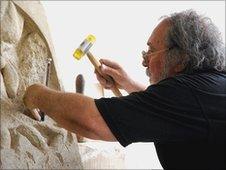

Alaa Hassan is working openly again, after death threats from al-Qaeda

Every once in a while, you meet someone whose individual life seems so intricately bound with momentous events, that it shines a light on history in the making.

Alaa Hassan is such a man.

I met him sitting at a workbench in the small garden in front of his Baghdad home.

He was tapping away with a chisel at his latest work of sculpture. Slowly, out of a blank piece of stone, the form of a woman was beginning to emerge.

But Alaa did not always work on such a modest scale.

Until the American-led invasion in 2003, he was one of former dictator Saddam Hussein's favourite monumental sculptors.

"I used to have a certain lifestyle," he said wistfully. "Under Saddam there used to be plenty of work. We would make lots of murals and monuments for his palaces."

Few people in Iraq would admit to missing Saddam Hussein, but many do look back with nostalgia to a more stable time.

Saddam humour

As he led me into his home, he told me he was no supporter of the regime. But as an employer, Saddam wasn't so bad, he said.

"Saddam was an easy person to get on with, at least with us artists," he said.

"He used to smile and he had a sense of humour."

Iraqi artists were kept busy during Saddam's rule

But when I asked him for an example of a Saddam-joke, Alaa left me mystified with a complicated tale about a statue and an oil-drum which might catch fire.

Perhaps you have to be a sculptor, or an Iraqi, or both, to get the gag.

Inside, Alaa produced a bulging plastic folder from a desk drawer.

It was stuffed with sketches and clippings and also old photographs.

These he keeps hidden, in case they cause trouble for him.

There was a picture of Alaa presenting a model of one of his works to Saddam Hussein.

In October 2002, just six months before the invasion, Saddam Hussein had commissioned Alaa to create a vast monument to the Iraqi nation.

The photograph shows a ring of gargoyle-like chimeras, grotesque figures, half human, half animal, representing the country's enemies. Inside the circle is an Iraqi family.

And at the centre of it all, there was to be a giant statue of the man himself, imperious and apparently strong.

'Upside down'

Of course the monument never got built. History intervened.

On 9 April 2003, American troops toppled that iconic statue of Saddam Hussein in the centre of Baghdad, as a jubilant crowd chanted and threw shoes.

Some of Alaa's works met the same fate: torn down or looted for scrap.

"Everything stopped. I had no work for four years," Alaa says.

"I just stayed at home. Everyone was talking about mass graves, and about what Saddam had done. Everything was turned upside down."

Alaa lost more than just his source of income.

Like many Iraqis, he lost his security, as the country descended into violence and religious fanatics tried to enforce their interpretation of Islam.

"I received death threats from al-Qaeda. They called me an infidel and told me to stop making sculptures. So I stopped. I was scared. I destroyed some of my works."

Alaa hopes that things are now slowly getting better. He is working openly again.

And, perhaps ironically, one of the most terrible events in Iraq's recent, violent history, part of that wider pattern of instability which deprived him of his livelihood, has now provided him with a commission.

New hope

On the last day of August 2005, a throng of Shia pilgrims was making its way across a bridge over the river Tigris to an important shrine.

Alaa Hassan's latest project marks the Shia drownings of 2005

Suddenly a rumour of a suicide bomber swept through the crowd, causing panic and confusion. People were crushed against the railings. Many were pushed into the water below.

There was no suicide bomber. But 1,000 people lost their lives that day.

One man, though, became a hero - a Sunni called Othman hurled himself into the river in a frantic attempt to save lives.

Just as Iraq was descending into a vicious sectarian civil war, in a story that has now become legend, Othman pulled seven of his Shia fellow countrymen to safety before he himself drowned.

The Iraqi government has commissioned Alaa to build a memorial to that tragedy.

Back in his home, he showed me his design. Around the base, Othman is frantically dragging a pilgrim out of the river, as others drown; out of the swirling chaos, a solitary hand stretches upwards, pleading for help.

When the work is completed, it will be 7m (23ft) tall: a monument, cast in bronze, to Iraq's fraught attempts at sectarian reconciliation.

But the continuing political uncertainty has put the project on hold.

And so, for the moment, it remains as it is - just a model in a sculptor's front garden.