The 104-year-old WW2 veteran who moved the Queen to tears

Yavar Abbas (left) shakes hands with Queen Camilla at the VJ Day 80th anniversary service

- Published

When Capt Yavar Abbas stood on stage in front of King Charles III and Queen Camilla on Friday, he wasn't expecting to make headlines.

He was at the official commemoration for the 80th anniversary of VJ - Victory over Japan - Day in Staffordshire as one of the last remaining veterans. Yavar was about to give a short address about his experience on the Asian front. But he decided to go off script.

He told the audience he wished "to salute my brave King who is here with his beloved Queen in spite of the fact that he's under treatment for cancer".

The King and Queen became visibly emotional. Yavar went on to tell the crowd he had been free of cancer too for the past 25 years, receiving a round of applause.

Yavar is 104, and his journey to this moment, which he told to me when I met him earlier this year, is extraordinary.

The King and Queen Camilla were seemingly moved to tears

He was born in Charkhari in British India, in what he describes as a "one-horse town". Officially his birth date is registered in 1921, but Yavar says he was born on 15 December 1920. He was a student when Britain declared war on Nazi Germany on behalf of India in 1939.

From early December 1941, there was a new enemy and a new front. Japan had attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor. Hours later, Japanese forces targeted British colonies in South East Asia. And in just a few months, Japan had taken territory that had been part of the British Empire for more than a century, including Malaya (now Malaysia), Singapore and Burma (now Myanmar).

By mid-1942 Yavar had to make an important decision - fight for the British or for Indian independence. He could not believe how quickly parts of the British Empire had fallen to Japan. There was a palpable fear that India could be next.

"I was not a supporter of British imperialism, in fact I detested it," Yavar tells me. At the time, there was a growing pro-independence movement calling for the British to "Quit India," which was brutally suppressed.

Yavar was aware fighting for the British would mean fighting a war in the name of freedom - while Indians were not free from colonial rule. But, like many Indian nationalists, he did not want Nazism and fascism to prevail.

"I had to choose and hope that if I joined the [British Indian] army, after the war, as they had been promising, I would get independence."

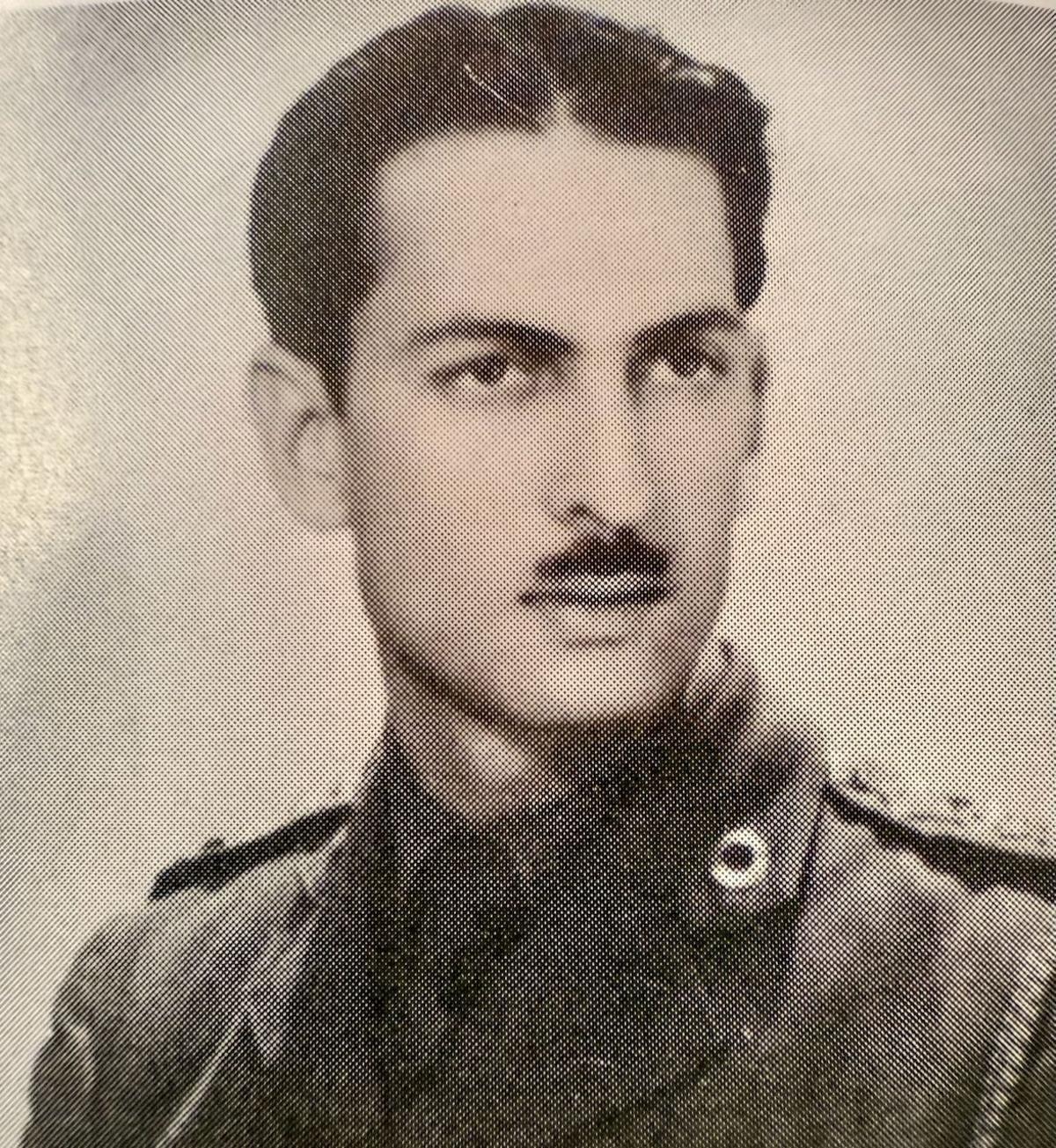

Yavar as a young man

So Yavar enlisted - and became one of around 2.5 million Indian soldiers to sign up. Initially he joined the 11th Sikh regiment and was posted to a "God-forsaken place" in a remote part of East Bengal, where he spent his days guarding a strategic site - and felt disappointed at the lack of action.

Attitudes among the British officers frustrated him too.

"I found myself in a version of Dad's Army, in the company of white, middle-aged men as my fellow officers, who still considered India to be a crown colony on which they'll have continuing control for the foreseeable future."

One day in the mess, Yavar spotted an advert in The Army Gazette for officers to be trained as combat cameramen. He applied and was soon accepted.

In this role he joined the newly formed British 14th Army, whose aim was to win back territory lost to Japan. The troops of this army were well-trained for jungle warfare, and had better equipment. A multi-national force, in time it would number up to a million soldiers - mostly Indian, but also from other parts of the British Empire - including West and East Africa.

This army felt completely different to Yavar: "It was wonderful camaraderie. There were British and Indians mixing with each other."

The Second Map

Marking the 80th anniversary of VJ Day, Kavita Puri tells the story of Britain's war against Japan during World War Two

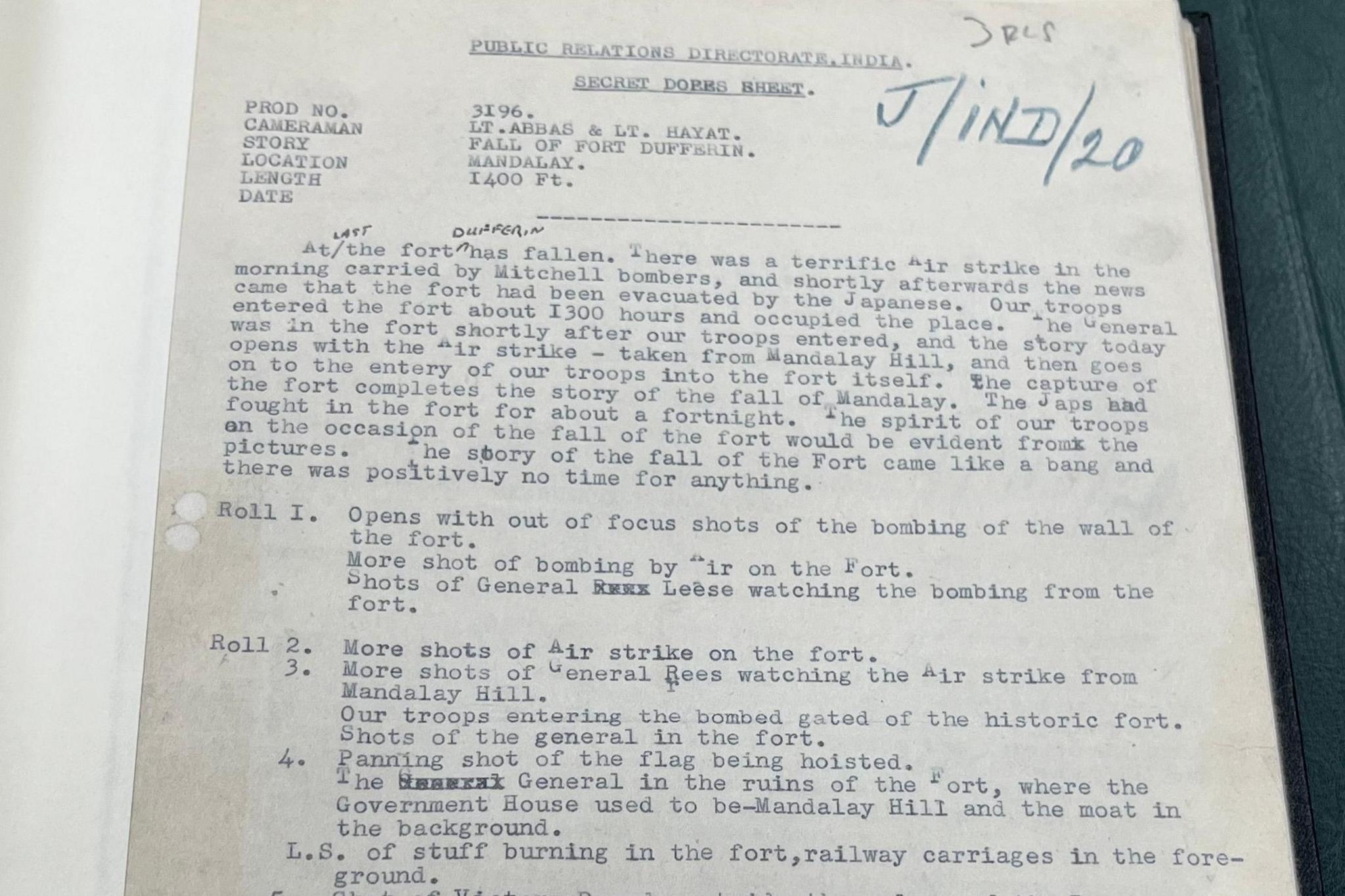

Yavar would go on to film on the front lines at many major Allied-Japanese battles of the Burma campaign from 1944. He would travel in his jeep with an assistant, armed with a pistol and a Vinten film camera, a tripod, and many rolls of film. He sent his rushes to Calcutta (now Kolkata), along with dope sheets explaining what the shots were. There they were edited, and the film distributed for propaganda or newsreels.

Yavar was at the siege of Imphal and the battle of Kohima when Japan invaded the strategic north-eastern Indian towns. Japan's aim was to cut off the Allied supply line to China. Repelling Japanese forces at Imphal and Kohima was hugely significant, because success in taking these towns could allow Japan to progress deeper into India and expand its empire.

These battles have been described by some historians as among the most significant of World War Two. British, Gurkha, Indian and African troops decisively halted the offensive into India. Tens of thousands of Japanese forces died. Many killed themselves rather than being taken prisoner in defeat.

The objective of the 14th Army was to win back British territory lost to Japan

Yavar cannot forget the aftermath of the battles. "It was a horrible sight, Japanese with swords sticking out of their bodies, instead of falling into enemy hands." The British advance to re-take Burma began afterwards.

Yavar was around 30 miles (50km) from Mandalay when he had a brush with death. He tells me how the Japanese put up stiff resistance, and the Allies couldn't advance, so they took cover in shallow trenches. He was in one with a Gurkha unit, but continued to film. He thinks a sniper saw his camera and shot towards him. The Gurkha beside him was hit in the temple and died. Yavar's camera shattered.

"I'm lucky to be alive," he says.

The Battle of Mandalay was a crucial one for the Allies. If they managed to take it, the road to the capital Rangoon (now Yangon), would be open to them. Yavar was in a tank, and decided he needed a better shot of the action. "I just climbed up on top of the trunk and started filming."

The turret opened and he was told by another officer to get down for his own safety. "It was a stupid thing to do, but that's the kind of thing you do when you're young."

Dope sheet describing footage from the battle at the Japanese stronghold of Fort Dufferin

The gun battle was intense and the aim was to capture the Japanese stronghold of Fort Dufferin. Yavar filmed the enemy positions being bombed relentlessly from the air.

"They kept on pounding them, pounding them, pounding them," he recalls.

I went to the Imperial War Museum in London and found the footage that Yavar filmed that day. Even without sound, the raw, unedited, black and white images are as dramatic as Yavar described. I returned to his home to show him the footage which he had never seen.

'We didn't achieve anything really': Yavar Abbas looks back at his own film

As he watched it, the events from 80 years all come back and he points at the screen as he remembers.

"That's my shot," he tells me as the British flag is raised in victory over the strategic Fort Dufferin.

He shakes his head watching the images. "It's bizarre to be sitting here and watching all that, and to think that I was in the middle of that."

He says he cannot believe now that 80 years ago he was happy to shoot Japanese forces with his camera, as well as his gun.

"I'm not very proud of that," Yavar says, "but that's how you feel when you are on the front."

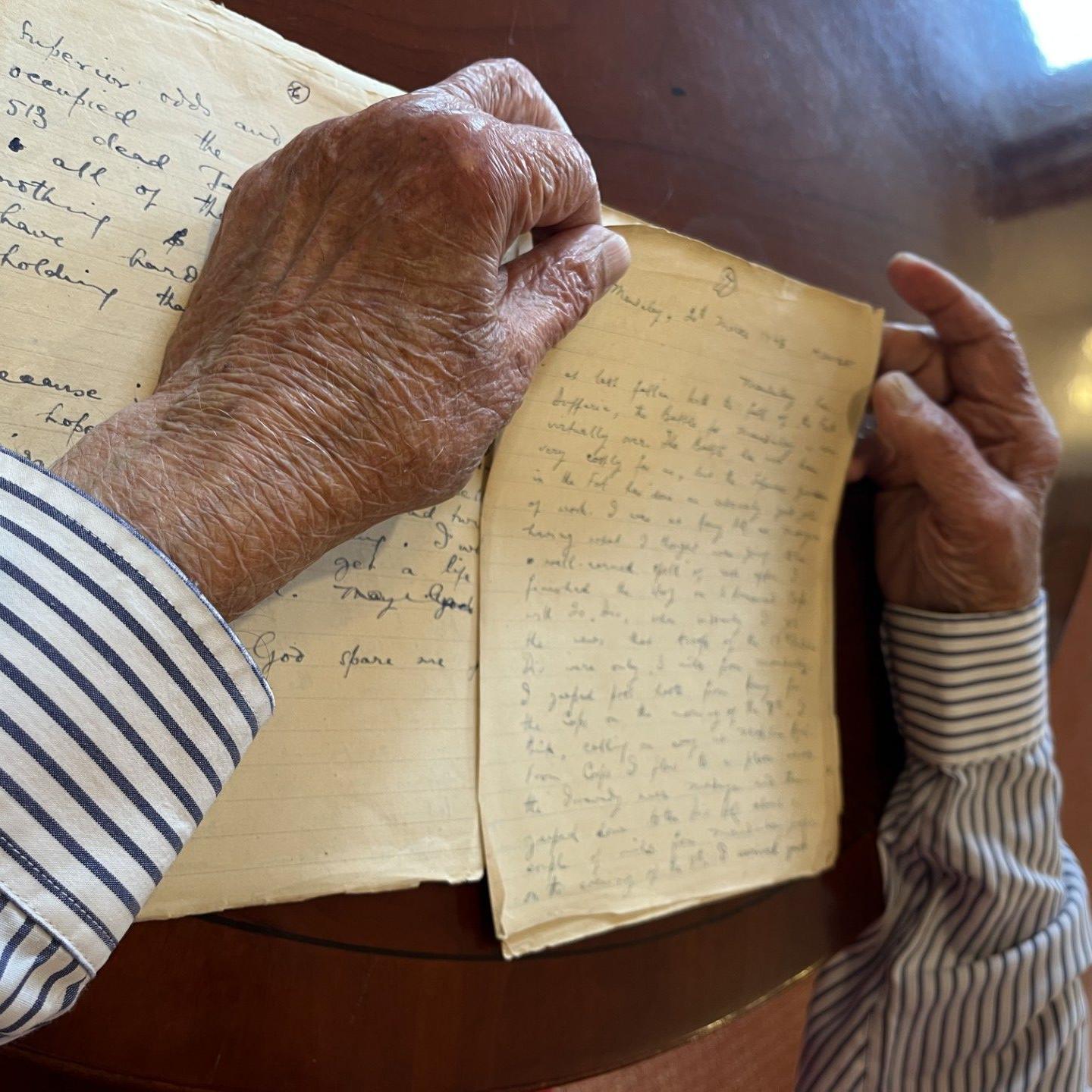

Yavar has something to show me, that he had found that morning. He takes out a faded notepad with loose leaves of paper that have yellowed with age. It's his diary from the front line. He had carried an ink pot with him in battle and written in the diary with his fountain pen. He reads out an entry from the day that Fort Dufferin fell on 20 March 1945.

"Thank goodness it is all over and that I'm still alive. I can still hear the noise of shelling not far away. Maybe it is the Japanese guns firing at the Fort. I'll find out tomorrow. Two o'clock in the morning now, and I must go to sleep."

Yavar shows the entry from his diary on 20 March 1945, the day Fort Dufferin fell

Yavar wonders aloud how in the midst of battle he found time to sit and write this when he had to be up again at five in the morning.

I ask him if he thinks he is brave. He looks at me as if that is a strange question. "Absolutely not," he says.

On VE Day, 8 May 1945 - when the war ended in Europe - Yavar was in Rangoon filming the recently re-taken capital. However, it was so inconsequential he didn't note it in his diary. Little had changed for him.

The war against Japan was still ongoing. But then, completely unexpectedly months later, America dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan unconditionally surrendered on 15 August 1945, the day that VJ Day is marked each year.

After the war, Yavar was posted with the 268 Indian Brigade as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces under the overall command of US Gen Douglas McArthur. He went to Hiroshima months after the bombing.

Yavar says he saw the wasteland and people with horrific injuries.

"There were no buildings, it was just one tower that was left. Otherwise the whole thing was flat."

It's the first time since we have spoken that Yavar's bearing changes - he has a look of horror as he remembers.

"It still haunts me," he says. "I couldn't believe that human beings could do this to each other. Hiroshima was a terrible experience."

The British did leave India, as Yavar had hoped. In August 1947, India was partitioned and two new states were born: Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

Yavar was a witness to the bloody aftermath, and was heartbroken at the decision to divide India. Two years later, he came to Britain.

He worked for many years at the BBC as a news cameraman travelling the world. He would go on to be an acclaimed independent film-maker, winning numerous awards.

Yavar worked as a BBC cameraman for many years

VJ Day - on 15 August - is not a day Yavar ever celebrates. Current events weigh heavily on him. Yavar's message, as one of the last remaining survivors of World War Two, is clear.

"War is a crime. War must be banned. I think it's mad. We didn't achieve anything really."

He says at the time he felt he was part of something worthwhile, for the sake of humanity - he doesn't feel that now.

The wars engulfing the world 80 years on - particularly Gaza - are on his mind.

"We seem to have learnt nothing," Yavar tells me. "The killing of innocent men, women, children, and even babies goes on. And the world, with some honourable exceptions, watches in silence...

"It was all futile, because it's still happening. We haven't learned anything at all."