Mars' entire surface was shaped by water

- Published

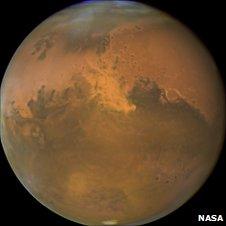

The surface of the Red Planet was shaped by water on a global scale

The whole of Mars' surface was shaped by liquid water around four billion years ago, say scientists.

Signs of liquid water had been seen on southern Mars, but the latest findings reveal similar signals in craters in the north of the Red Planet.

The team made their discovery by examining data from instruments on board Europe's Mars Express and Nasa's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

They report the findings in the latest issue of the journal Science.

John Carter, of the University of Paris, led the team of France- and US-based scientists.

"Until now, we had no idea what half Mars was made of in terms of mineral composition," he told BBC News.

"Now, with the Esa and Nasa probes, we have been able to get a mixture of images and spectral information about the composition of the rock."

He explained that these instruments had revealed clay-type minerals called phyllosilicates - "the stuff you would find in mud and in river beds."

"It's not the species of mineral itself that's important," said Dr Carter, "it's more the fact that the minerals contain water.

"This enhances the picture of liquid water on Mars."

Liquid rock

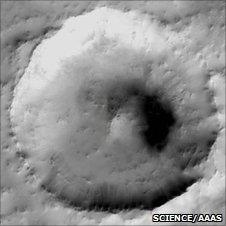

Previously, researchers have seen similar signs of water in the highlands of southern Mars in rocks that are up to four billion years old. But in the northern part of the planet, more recently formed rocks have buried the older geology.

The prevailing theory for why this is, is that a giant object slammed into northern Mars, turning nearly half of the planet's surface into the Solar System's largest impact crater.

The team found the minerals in craters in the northern part of Mars

Dr Carter explained that this meant a thick veneer of younger rock covered the older geology, "so the craters are the only way of accessing the older stuff".

But the craters are relatively small and more difficult for the orbiting probes to take measurements from.

"There's also ice and dust coverage in the north of the planet, making it harder to get signals from these craters," said Dr Carter.

The new findings suggest that at least part of the wet period on Mars, that could have been favourable to life, extended into the time between that giant impact and when volcanic and other rocks formed an overlying mantle.

This indicates that, 4.2 billion years ago, the planet was probably altered by liquid water on a global scale.

But Dr Carter said that the findings did not paint a picture of huge Martian oceans.

"It was probably a very dry place," he said. "But we're seeing signals of what were once river beds, small seas and lakes."

- Published3 June 2010