David Livingstone's 'lost letter' deciphered

- Published

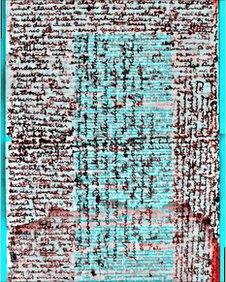

Powerful lights and cameras were used to reveal the letter's secrets

The contents of an "indecipherable" letter written by David Livingstone shortly before he met Henry Stanley have been revealed for the first time.

The so-called Letter from Bambarre was scribbled by the Scottish explorer on torn-out book pages in February 1871.

Livingstone's writing had faded so badly it was impossible to read but scientists used spectral imaging technology to recover the text.

It condemns slavery, relays details of Africa and reveals his ill health.

The letter was written when Livingstone was stranded as a virtual prisoner in extreme environmental conditions at Bambarre in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The missionary had run out of writing paper and was suffering from loneliness and extreme ill health following bouts of dysentery, fever, pneumonia, and horrific tropical ulcers on his feet and legs.

Livingstone's iron gall ink has bled through the page, in effect creating two layers of text superimposed on one another.

This problem was compounded by Livingstone's method of writing, which weaved an unsteady course around the margins of the page before it meandered vertically across the horizontal print of the journal.

In order to read the text, the research team illuminated the letter with successive wavelengths of light, separating the text layers, as a 39 megapixel camera scanned the pages.

The unveiling of the letter's content marks the start of a major project looking at Livingstone's final diary from 1870-71 which has never been published in its original, unabridged form.

The work is being done by researchers from Birkbeck College, University of London, working with colleagues at the National Library of Scotland and the David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre.

They said the four-page letter provided an insight into Livingstone's state of mind at a critical period in his final years in Africa, when he was searching for the source of the Nile.

It was written to Horace Waller, a close friend and Livingstone's future biographer.

The letter includes some of his thoughts on the "awful traffic" of the slave trade, which he said could be "congenial only to the Devil and his angels".

"If our statesmen stop the frightful waste of human life in this region and mitigate the vast amount of human woe that accompanies it they will do good on the large scale and cause joy in Heaven," he wrote.

Livingstone died just two years after the letter was written

The prospects for commerce and Christianity in the African interior, and details of the lakes and rivers of Central Africa are also included in the letter.

Fiercely competitive, he was openly critical in the letter of the achievements of his fellow explorers Samuel White Baker, Richard Burton, and John Hanning Speke.

And he expressed his disgust and disillusionment with the British government's policy of laissez-faire in Africa and the Middle East.

But the letter also reveals the private man behind Livingstone's heroic public image.

Livingstone wrote: "I am terribly knocked up but this is for your own eye only: In my second childhood [referring to his lack of teeth - several of which he extracted himself] a dreadful old fogie. Doubtful if I live to see you again."

Despite his ill-health in the midst of a cholera epidemic which devastated the local population, he wrote of his determination to complete his search for the source of the Nile.

"Well I am off in a few days to finish with the help of the Almighty new explorations," he wrote.

It is thought that, when he finally left Bambarre on 16 February 1871, Livingstone entrusted his letter to an Arab trader named Mohamad Bogharib, with whom he had previously travelled.

When he returned in September, Livingstone found that this letter was still with Bogharib in the same village.

The subsequent fate of the letter is unknown.

But it is likely that after his famous meeting with Livingstone in late 1871 - when he reputedly greeted the explorer with the famous words: "Dr Livingstone, I presume?" - Stanley carried the letter back to England in 1872, where it was finally delivered to Waller.

Livingstone was to die a year later in Zambia from malaria and internal bleeding caused by dysentery.

Many of the details included in the letter and diary were apparently suppressed by Waller, who edited the posthumously published Livingstone's Last Journals in 1874.

In this Victorian classic, Livingstone emerges as a hero, an anti-slavery crusader, and a martyr.

Waller's careful editing secured Livingstone's place in British iconography as a saint-like figure and champion of the oppressed, but he was economical with the truth when it came to the man himself.

The letter disappeared off the map for almost a century before it resurfaced at a Sotheby's auction in 1966, and was purchased by the American photographer and diarist Peter Beard, in whose private collection it still remains.

Dr Debbie Harrison, the project's contributing editor and medical historian, said: "His closing line to Waller indicates Livingstone's anxious and depressed state of mind.

"He did not know that in just a few months Stanley would arrive, bringing desperately needed food, medicines and the longed for news from an outside world he thought had forgotten him."