Drug gang violence casts shadow over Mexico elections

- Published

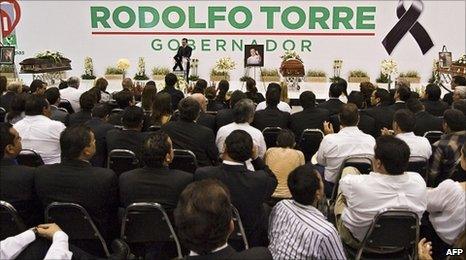

Rodolfo Torre was killed as he campaigned to be governor in Tamaulipas

Sunday is election day in more than a dozen Mexican states, with voters set to choose governors, state deputies and mayors.

Attention will not just be on the results but on how polling day unfolds given the wave of violence that has marred campaigning in some areas.

Mexico's powerful drug gangs have been blamed for much of the violence, a sign, according to some, of the growing influence of organised crime in the country.

For months, candidates in many of the 14 states holding elections have complained of intimidation by alleged criminal gangs that has forced them to adopt special security measures and limit their campaigning in high-risk areas.

In areas of the country worst-hit by the drugs conflict, which has left some 23,000 people dead since late 2006, political parties admit they have found it hard to find citizens willing to run for office.

One person ready to stand was Rodolfo Torre Cantu of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), who was favourite to be elected governor in the north-eastern state of Tamaulipas.

Mr Torre had spoken about his priority, if elected, to boost security in Tamaulipas, a key battleground between two powerful gangs, the Gulf Cartel and the Zetas, over drug-smuggling routes into the US.

But on 28 June, gunmen ambushed a convoy carrying Mr Torre and his team, shooting him and four of his aides dead.

Mr Torre's murder - the highest-profile political killing in Mexico since the assassination of presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio in 1994 - has deepened concerns over how Mexican democracy is suffering at the hands of organised crime.

"There is an escalation in the influence of the drug cartels in Mexican politics," says Lorenzo Cordoba, electoral expert from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Many see the threats and intimidation of this year's election campaigns as evidence of how Mexico's drug conflict has permeated into the political system.

"Almost all members of my campaign team have received dozens of calls," Xochitl Galvez, a candidate for governor of the state of Hidalgo, told the BBC recently.

The callers "identify themselves as members of organised crime", she added.

The head of the National Action Party (PAN), Cesar Nava, also said recently that many of his party's candidates had received threats which he attributed to the Zetas.

A mayoral candidate for the PAN in Tamaulipas was killed in an attack in May.

The violence has reignited the debate about President Felipe Calderon's decision to take on the cartels and deploy thousands of troops in violent hotspots.

Decoys

The candidates on the ground have meanwhile learned to take extreme precaution when out trying to win votes.

President Calderon urged unity in the face of the violence

Take for example the northern state of Chihuahua, where Ciudad Juarez - Mexico's most violent city - is located.

The state's electoral institute was forced to ask for extra protection for candidates who are afraid of campaigning in areas like the valley east of Juarez, a crucial drugs route into neighbouring US territory.

Jorge Abraham Ramirez, the PRI's candidate for state legislator in Ciudad Cuauhtemoc, in central Chihuahua, says that he has taken special security measures on the campaign trail.

"We do not make our daily schedule public, and many times we use decoys. We announce we are heading for one place and then carry it out it another," he told the BBC.

Alex Lebaron, a fellow candidate in Nuevas Casas Grande, Chihuahua, told the BBC that his team had decided not to hold rallies during the evening and that they kept a low profile when canvassing some areas.

Disruption

Many in Mexico think that local elections are the perfect chance for the drug gangs to flex their muscles - mayors control local police forces and, by being in charge of specific territory, are valuable targets for the cartels' pressure tactics.

Concern is now focused on how violence could disrupt election day and dissuade voters from going to the polls.

The federal authorities say they will deploy extra security forces to make sure the election goes according to plan and that safety for voters can be guaranteed.

Electoral officials sound optimistic.

"Many said we wouldn't find enough people to man the ballot stations around the state," says Fernando Herrera Martinez, president of the Chihuahua electoral institute. "But we are ready, 100%, to hold the election."

But the violent campaign, electoral export Lorenzo Cordoba believes, shows how Mexicans citizens have become all too used to news of drug-related crime.

"It's a regrettable scenario, in which the violence has started to form part of the daily landscape of Mexico," he says.