Why I spend hours painstakingly repairing banknotes

- Published

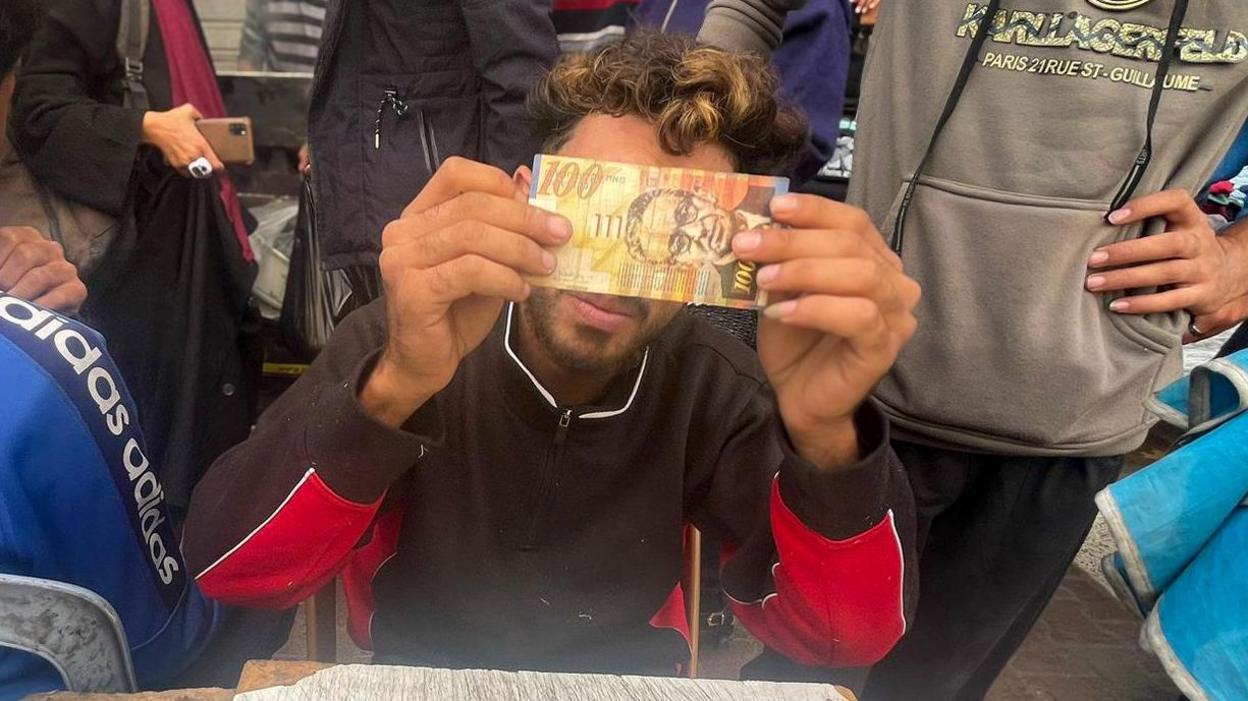

In a bustling Gaza City market, a money repairer expertly inspects a worn, yellow 100 shekel ($30.50; £23.10) note. He straightens it out and enhances its faded colour with careful strokes of a pencil.

Baraa Abu al-Aoun should have been studying at university - but instead he ekes out a living from a table he has set up at the roadside, taking a small sum to help keep cash in circulation.

Fixing banknotes is a thriving new business in Gaza.

Ever since the deadly Hamas-led attack on Israel in 2023 and the devastating war that ensued, Israel stopped transfers of banknotes, along with most other supplies.

Most banks were destroyed in Israeli strikes, and many were looted. While some branches have reopened since a ceasefire took effect seven weeks ago, there are still no working ATMs.

But people need cash to buy food and essentials. That has forced them to turn to informal money merchants who charge enormous commissions to turn digital transfers into cash. It has also sparked a huge increase in the use of e-wallets and money transfer apps.

And it means that every existing banknote matters more than ever - no matter how tattered. That's where Baraa comes in. "My tools are simple: a ruler, pencils, coloured pencils and glue," he says.

"The ceasefire hasn't changed the financial situation. What I do now is to serve people and help them."

Watch: Baraa Abu al-Aoun carefully restores a banknote

Gaza's economic collapse has been so catastrophic during two years of intense war that a new UN report says its entire population of more than two million has been pushed into poverty.

Four in five people are now unemployed according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad), and even those who still have an income or savings struggle to access cash.

"It's pure suffering and nothing else," says Numan Rayhan, who is displaced in Gaza City from Jabalia in northern Gaza with few belongings. "Shortage of income, shortage of money, no cash flow from the banks."

Early in the war, Israeli strikes targeted banks, which Israeli officials alleged were linked to Hamas. Their vaults were looted by armed Palestinian gangs, some presumed to have been Hamas. The Palestine Monetary Authority (PMA) has previously said that cash worth about $180m (£136m) was stolen.

Cogat, the Israeli defence body which controls Gaza's border crossings, confirmed that in line with a political order "and due to Hamas's reliance on cash to maintain its military activity", Israel has not been allowing cash to enter Gaza.

The lack of cash circulating has "caused problems for both sellers and buyers", says Zakaria Ajour, a stall-holder at another market in Gaza City. People don't want to accept worn and delicate notes at face value any more, "if there are even small scratches or pieces of tape on a note.

"Some customers come to me just because they want small change for transport, but I don't have change," Mr Ajour goes on. "Ten-shekel coins are barely found, and even when they are, they have virtually no value because of inflation due to the cash crisis."

Now, there are long lines outside the Bank of Palestine in Gaza City, one of nine branches of five banks that have reopened. Customers can only reactivate frozen accounts, open new ones, or sign on to banking apps.

Asmaa al-Ladaa wants to set up an account so that she can receive money directly from her relatives living outside Gaza."The whole process is just chaos and crowds," she says. "We woke up at 06:00 and left our children behind in a tent. We left everything just to come to the bank."

In the southern city of Khan Younis, where the banks are too badly damaged to reopen, Abu Khalil has just returned from a trek to central Gaza. After spending much of the day queuing, he did not manage to enter the bank there, and despairs at the idea of having to go back again.

The grandfather still receives a monthly salary of about 2,000 shekels ($612; £463) from the Palestinian Authority, but says that almost half of his income goes on charges he pays to vendors or money merchants. "You have to pay the fees. There's no alternative," he complains.

During the war, adapting to the urgent need for cash, many small businessmen who previously offered money transfer and exchange services began charging customers high commission to turn electronic transfers into cash. On occasion it has reached 50%, although it has recently dropped.

One money merchant, who wishes to remain anonymous, tells us that market forces determine commission rates. "Our work is directly tied to market activity and the entry of goods and aid," he says. "When there's an inflow of goods, and active buying and selling, the commission drops significantly, sometimes down to as low as 20%. But when the crossings close, the rate rises."

Electronic transfers through bank apps - for which shop and stall owners charge minor fees - have become a popular workaround for Gazans making purchases, even of small items.

The PMA, which acts as a financial regulator, has launched a payment system allowing instant transactions between local bank accounts. For those without accounts, The Bank of Palestine offers e-wallets and says there are now more than 500,000 users in Gaza. These transactions can be done without an internet connection or app, using text services on any mobile phone.

E-wallets are being used to send financial aid directly to needy families, by humanitarian agencies including Unicef and the World Food Programme. Since early last year, Unicef says it has been able to make cash transfers to about a million people - half of them children. It prioritises vulnerable children, including amputees and orphans, and pregnant or breastfeeding mothers.

"Basically, you can go to the grocery store and the phone is used as a payment card, you can buy with it," explains Jonathan Crickx from Unicef. "That allows a very high traceability of how the money is actually spent. From what we observed, 99% of all beneficiaries are spending first on food and water, second is hygiene items, like soap, and third is electricity through generators."

Mr Crickx says he has personally witnessed families having to buy 2kg (4.4lb) of tomatoes for about $80, and 5kg (11lb) of onions for $70.

Hanan Abu Jahel, who is displaced from Gaza City and lives in a camp in al-Zawaideh in central Gaza with her extended family, recently received 1,200 shekels ($367) from Unicef. She used it to buy basics like rice, lentils and pasta.

But she says: "My children need vegetables, fruits, meat and eggs. My youngest son especially craves eggs, but I can't get them as prices are still so high and I have to cover the needs of 12 people."

US President Donald Trump's 20-point peace plan promises an "economic development plan to rebuild and energise Gaza", convening "a panel of experts who have helped birth some of the thriving modern miracle cities of the Middle East".

It envisages new investments and "exciting development ideas" that can "create jobs, opportunity and hope for future Gaza". But there are no details about how to begin to generate growth and stability, just as the UN's trade agency warns that the strip is going through the most severe economic crisis ever recorded.

Back in Gaza City, Baraa Abu al-Aoun holds the banknote he has been working on up to the light. expertly. He has more customers waiting, attracted by his sign promising repairs "with high professionalism and without adhesive tape".

As Baraa toils on, he longs for a return to a normal life with prospects of more profitable employment.

"I just want this war to end fully," he says. "My hope is to feel relief at last, so that I can study and work with a degree.

"In Gaza, we're just surviving. We're not human beings anymore."

More weekend picks

- Published16 November

- Published7 September