Smos 'space chopper' returns first global maps

- Published

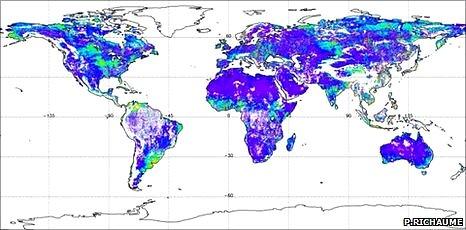

The soil moisture map incorporates three days of data from last week

Europe's Smos mission is slowly but surely meeting the challenge of measuring soil moisture and ocean salinity from space.

The satellite, launched late last year, is attempting to make global maps of these two important parameters using an innovative detection technique.

Its sole instrument, an 8m-wide interferometric radiometer, gives Smos the look of a "space chopper".

But the satellite's early data would indicate its approach is effective.

Mission scientists presented some of the first global maps at the European Space Agency's Living Planet Symposium here in Norway's second city.

The Smos instrument has the look of rotor blades on a helicopter

Such data is expected eventually to have wide application, informing climate studies, weather forecasts and warnings of extreme events, such as flooding.

The map shown at the top of this page illustrates the wetness of soils worldwide.

"It comes from three days of Smos observations made last week. Blue is dry and red is wet," says Dr Yann Kerr, one of the mission's two principal investigators.

"Where it is white, it's because we were not able to do a retrieval. These are places like the Amazon Forest where we are not quite confident yet about the results, or there's interference, or bias because we have snow, such as over the Himalayas," the Cesbio, Toulouse, researcher told BBC News.

The Esa satellite's radiometer works by measuring the natural emission of microwaves coming up off the planet's surface. Variations in the sogginess of the soil or the saltiness of the oceans will modify this signal.

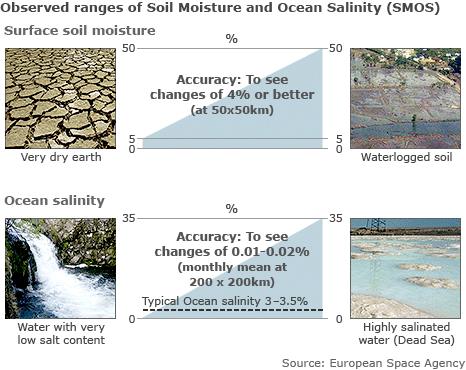

The amount of water retained in soils tends to range from about 5% to about 45-50%. At more than 50%, the ground becomes water-logged and any excess liquid will simply run off.

Smos aims to see steps of about 4% on this range across 50km-wide segments of the Earth's surface. This should enable it to determine about 10 or 11 classes of soil moisture.

But this endeavour has been frustrated in many parts of the globe by interference from man-made emitters which bleed into the Smos frequencies and blind the instrument. These sources include military radars, radio links and TV masts.

The natural signal has been polluted across great swathes of Europe, Africa, the Middle East and the Far East. Embarrassingly, Spain, which is a key partner on Smos, was found to have some of the worst interference.

Indeed, a project in the Valencia area to "ground truth" Smos data by comparing it with physical soil and seawater samples was delayed by the problem. Some of the interference was traced to a wi-fi network around the city hall.

But this issue is gradually being addressed by getting transgressors to switch off their equipment. The Smos data processors are also learning tricks to "clean" the signal.

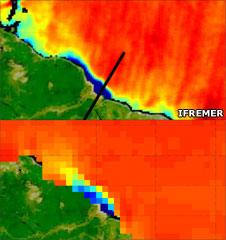

The Smos data (top) compared with a model based on Argo float data

Good progress was reported in Bergen, too, on the acquisition of ocean salinity data. In some ways, the task of measuring this parameter is even more challenging.

Although the salt content of water can range up to more than 30% (the Dead Sea), typical values in the oceans tend to be in a tight band around 3-3.5%. Smos is aiming to see steps of 0.01-0.02%, averaged monthly, at a scale of 200km.

This page shows a Smos image of freshwater emerging from the Amazon River and mixing with the Atlantic.

"You see the outflow from the Amazon," said Dr Kerr. "This is March, and so at this time of year the outflow moves north. Orange is normal seawater, yellow is less salty, and blue is the plume from the Amazon."

The Smos data is a good match with the modelled dispersion built from information acquired by the Argo buoy system which directly samples ocean salinity.

The European spacecraft is still in its commissioning phase. Some of the first, fully processed data will be distributed next week to science teams most closely connected with the mission.

A wider release to the scientific community should occur in September.

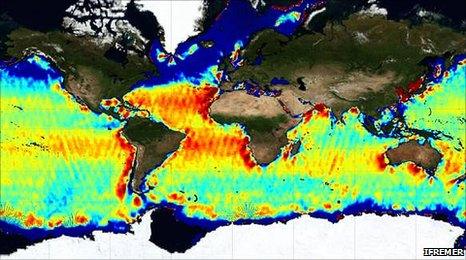

Smos ocean salinity map from March. Normal seawater is mid-green in colour; more saline waters are rendered in warmer colours

- Published29 June 2010