Selebi case like a crime novel

- Published

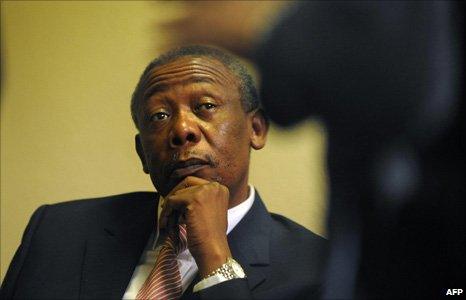

The trial of Jackie Selebi - South Africa's first black police chief - has gripped the nation.

Sharing the stage in what reads like a John Le Carre novel was a mafia drugs boss, a mining magnate and multi-millionaire Zimbabwean businessman.

A witness wept on the stand, there were allegations of money being handed over in brown paper bags and spy games.

Intrigue, obfuscation and patronage have characterised the case.

In the end though - despite his political links, Selebi has been left crestfallen: Guilty of corruption on an obscene scale.

At the end of the case, Judge Meyer Joffe said: "Every day society in general relies on the honesty and truthfulness of policemen and women… It is not an example that must be emulated by members of the Saps [South African Police Service]."

As he points out, this case speaks of so much more than Selebi, a man who helped shape the geopolitics of the new South Africa, being seduced by cash, fine dining and gifts of the latest designer suits.

It is about cronyism and the politicisation of South Africa's intelligence services as it confronts the fight against crime.

When charges were laid against Selebi, it came at one of the most turbulent times in South African politics.

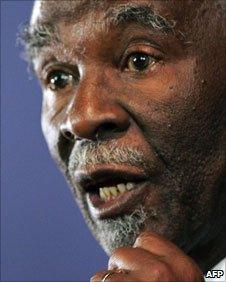

It was 2007 and the power struggle between then-President Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma, who was to succeed him, was reaching fever pitch.

'Hung out to dry'

Selebi enjoyed a close relationship with Mr Mbeki and had thought himself immune from prosecution when questions started emerging about his dubious friendship with Glenn Agliotti - a convicted drug baron.

But according to Ferial Haffajee, who was the editor of the Mail and Guardian newspaper at the time, Selebi was "hung out to dry".

The National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), which resisted pressure to back down and endured politically inspired changes of personnel at the top, was against the odds finally able to bring the case to court.

Selebi, as head of the police, was among those behind the dismantling of the elite investigation unit known as the Scorpions, which under the stewardship of the NPA, was charged with investigating some of the country's biggest crimes.

In 2008 when president, Thabo Mbeki suspended Mr Selebi as police chief

He claimed that having an elite body separate from the police would undermine the fight against crime and that its officers colluded with Western intelligence agencies bent on undermining South Africa's sovereignty.

And in the long competition between the Scorpions and the police, it was the police who won.

The Scorpions have now been disbanded and replaced by what many consider a less robust crime fighting team - the Hawks.

But Selebi always maintained that he was a victim of "malicious prosecution" because of this rivalry between the two forces.

'No free lunch'

"Throughout that period we as journalists could mark when our intelligence services began to be politicised and when crime fighting began to be politicised," says Ms Haffajee.

It was then that the "turf war between Scorpions and cops became very damaging", she says.

Although Mr Mbeki is no longer president, there are some serious questions for the current administration.

For example on the appointment of political figures to senior positions within the civil service and in particular the police.

Adriaan Basson who is writing a book about the Selebi case, has warned President Zuma to take note.

"A lot of the people who were protective and loyal to Jackie Selebi are still in the police," warns Mr Basson.

"They are also very senior in the intelligence services, and so we need to ask ourselves as South Africans whether the police have the capability to fight crime and fight corruption in the police."

Every legal tool was used to try to stall the trial but in the end it proved futile.

Judge Joffe concluded there was no evidence of an agreement that Agliotti benefited from his friendship with Selebi - in other words there was no signed contract between them.

But Selebi must have known that there is no such thing as a "free lunch", he said.

It is a lesson that many are hoping the new South Africa remembers well.

- Published2 July 2010