Laos hydropower a 'battery' for power-hungry region

- Published

Hydro power should help Laos become the "battery" for this increasingly power-hungry region, the government hopes

At first glance, the vast body of water stretching across the Nakai plateau does not seem to have much in common with a set of Duracells.

Up in the hills of central Laos, it shimmers to the horizon, punctuated by treetops breaking the surface and long-tail fishing boats buzzing past.

"I think they could turn this place into a tourist attraction," says 75 year old Kam Kong, as he untangles his nets on the edge of the water.

This postcard-perfect scene is actually the reservoir for the Nam Theun 2 dam - one of the biggest hydroelectric projects in Southeast Asia.

Its opening may mark a turning point for Laos as it hopes to move from being the sleepy, under-developed backwater of Indochina to, as its government has put it, the "battery" for this increasingly power-hungry region.

'Resource curse'

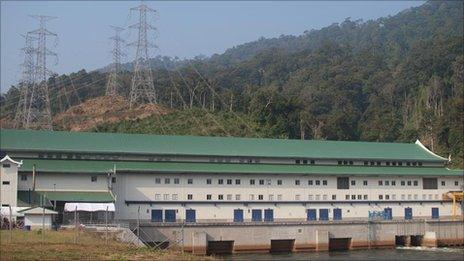

As the water is released from the reservoir, it rushes downhill and into a rather utilitarian white-and-green power station, where turbines hum as they produce more than a thousand megawatts of electricity.

Former farmer Kam Kong has been retrained as a fisherman and he also has a shop

Pylons march across the hill into neighbouring Thailand, which is taking almost all the power produced by Nam Theun 2.

In theory, the figures should add up nicely for Laos. Revenue from the project may bring the government some $2bn over the next 25 years, a serious amount for one of the world's least-developed countries.

According to one of the project's backers, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Nam Theun 2 could provide almost a tenth of the national budget in a good year.

But the spectre of the so-called "resource curse" hangs over any developing country that suddenly gains a windfall from energy, with funds siphoned off by a greedy few instead of being used for the greater good.

Villagers affected

Hydropower may be preferable to the alternatives; coal, gas or nuclear power

Laos insists that is not going to happen this time, despite its low ranking on Transparency International's "perceptions of corruption" index.

"Nam Theun 2 is business, but we need the revenue for the development of the country," says Sivixay Soukkharath, a government worker in charge of resettling villagers affected by the dam.

"The government will give people education, healthcare and infrastructure, and it will allow us to protect the environment throughout the country."

The financial deals Laos signed with the ADB and the World Bank to set up the $1.2bn project stipulate that revenue from the sale of electricity has to be used in this way.

There are also provisions for re-settling the 6,000 people whose villages disappeared under the reservoir - and tens of thousands more living downstream who have been affected by higher water levels.

'Struggling to adapt'

Kam Kong used to be a farmer.

Now, like other villagers on the Nakai plateau, he has received training on how to make a living from fishing, and also runs a small shop at the edge of the reservoir.

He has no regrets about seeing his old home underwater.

Sivixay Soukkharath, a government worker in charge of resettling villagers, warns about future projects

"To be frank, I don't miss a lot of things from the village," he says.

"At our new place, we have roads and electricity. We can take care of ourselves now. I'm very happy."

But other people are concerned.

Some pressure groups say that not enough has been done to make sure the displaced villagers have been given sustainable, alternative livelihoods.

One organisation, International Rivers, said that communities affected by the dam were "struggling to adapt" to changes in the environment.

It has asked the World and Asian Development Banks to hold back on financing other dams in Laos until they can guarantee the projects will not cause damage to the environment - or the people who have to make way.

Thorough assessment

But discouraging the development of hydropower projects may be a thankless task.

Views from the new Nam Theun 2 dam

There are at least nine in various stages of planning in Laos alone - and many more planned by other countries in the Greater Mekong sub-region.

Some propose damming the mainstream Mekong, the great river upon which millions of people rely to provide their fish catch and fertilise their rice paddies.

Nobody is sure what level of impact these dams would have if they were built.

But the Asian Development Bank says it will not consider funding any of these projects until a thorough assessment has been made.

Enormous challenge

That may not stop money coming from other sources.

Southeast Asia's rapidly developing countries either crave electricity, or the revenue that may come from generating it.

The Nam Theun 2 stakeholders had hoped their project might serve as a model for environmentally-sensitive, socially-inclusive hydropower.

But Sivixay Soukkharath admits that future developments in Laos might not follow its example.

Even if the hydropower projects are delayed, the alternatives are hardly more palatable for environmentalists: coal, gas or nuclear power stations.

Living without electricity is, understandably, becoming increasingly unacceptable for people in this region.

Providing it in a way that is sensitive to the environment and vulnerable communities is likely to be an enormous challenge.