Freedom Riders reunite after 50 years

- Published

Women like Carol Ruth Silver played a key role in the Freedom Riders movement

Fifty years after the so-called Freedom Riders risked their lives trying to break the practice of segregating people on the US public transport system, the veteran activists have reunited to inspire a new generation.

"We changed American history," says Bob Filner, now a California congressman. "And we should do the same thing today."

Just across the road from Filner is the old Greyhound station where he and hundreds of other Freedom Riders were arrested in the summer of 1961.

This week, many of them have come back to Jackson, Mississippi to mark the anniversary of their remarkable journey - desegregating buses, lunch counters and restrooms all the way from Washington to New Orleans.

But in the bars and meeting rooms, discussions move swiftly from the achievements of yesterday, to the problems of today.

"I don't care whether the issue is healthcare or housing or the environment, we should be applying non-violent, direct action to these struggles," says Filner.

The Freedom Riders have been swapping stories with young people from all over the US who've joined them in Mississippi.

"Racism hasn't gone away," says 14-year-old Naija Tyler from Harlem. "In New York, on 42nd Street, you hear racial comments. You go into an expensive store and it's like, 'Why is she in here? She can't afford stuff.'"

Back in 1961, Jim Crow customs ruled the Deep South. Despite a Supreme Court ruling making segregation on interstate buses illegal, black passengers were still expected to sit at the back.

The Freedom Riders refused to abide by convention, infuriating the white supremacists of the Ku Klux Klan.

On 14 May, a white mob attacked a Greyhound bus carrying Hank Thomas and six other activists as well as regular passengers, near Anniston, Alabama.

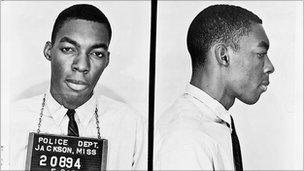

Hezekiah Watkins was one of the Freedom Riders

Its tyres were slashed, and the bus hissed to a halt. A firebomb was lobbed through the back window, filling the air with poisonous smoke.

"I knew I was going to die," recalls Thomas, aged 19 at the time. "It was a question of the best way to do it: leave the bus and be beaten to death, or stay and burn?"

An exploding fuel tank saved his life. The crowd retreated, allowing the suffocating passengers to clamber free.

A second group of activists was badly beaten on arrival in Birmingham, Alabama. It looked as though the Freedom Rides would have to be abandoned. But a group of students in Nashville vowed to continue. Civil rights leader Martin Luther King issued a rallying cry.

Throughout the summer, wave after wave of young black people, and white, poured into Mississippi aboard buses and trains.

The young Kennedy administration was torn. President John F Kennedy was distracted by foreign affairs. His brother Bobby, then Attorney General, sympathised with the Riders, but considered them reckless. He appealed for a cooling off period.

His pleas fell on deaf ears.

"We were not prepared to cool off," says Fred Clark, a Freedom Rider from Mississippi. "We had been pushed back as far as we could be pushed, and held as long as we could be held. It was straight ahead."

And straight to jail. The authorities in Jackson were routinely arresting activists as they stepped off the bus, and charging them with a breach of the peace.

As the local jails filled up, many of the Freedom Riders were sent to the feared state penitentiary, Parchman.

Hank Thomas was among them. He and his friends didn't expect to survive the experience.

Hank Thomas, one of the activists who found himself in Parchman penitentiary

"We knew about Parchman, and we knew that if a black man was killed by a prison guard, people just shrugged their shoulders. It minimised the paperwork."

The prisoners found an effective way to keep their spirits up - and infuriate the guards. They sang Buses Are A-Coming and other freedom songs all day.

The key, according to Freedom Rider Bob Filner, was finding ways to keep their minds and bodies active.

"We were given a slice of white bread with every meal. It turns out that if you chew it up, it has a consistency like paper mache. People started sculpting chess pieces."

Victory came in September that year, with a ruling that all interstate buses and terminals must be colour-blind. And this time it was to be enforced. Segregation's days were numbered.

.jpg)

Freedom Riders were arrested for challenging segregation

The Freedom Rides' impact on American society was profound. An unarmed group of young activists had proved that determination and personal sacrifice could overcome violent opposition.

It's a message they are now driving home to another generation.

"You can be more effective agents of change than we were," Filner tells students. "You've got Facebook, you've got Twitter, you've got all the social media we didn't have."

"Yes, but first we have to raise the consciousness of our young people," says Lew Zuchman, a former Freedom Rider who now helps disadvantaged children in New York.

"We must help them understand there's nothing wrong with them: there's something wrong with the world they're growing up in."

The young people listening are receptive to the principles forged by that historic ride.

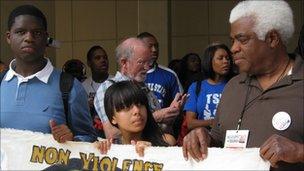

Th activists hope to inspire a new generation to embrace their non-violent direct action traditions

"This trip has changed my perspective and made me braver," says 16-year-old Eloise McAviney, from Queens, New York.

"I just heard someone making homosexual slurs, and I thought about the Freedom Riders and what they did, and I spoke up. It made me feel good about myself."

Naija Tyler agrees. "Before I met the Freedom Riders, I felt like I had a small voice, but now I see what small voices can do together. They can shout.

"It makes me want to go back and do something for Harlem - change the gang violence, the drugs, the immigration issues. They took the ride, and so should we."