Stateless Burmese Rohingyas lament India 'hardships'

- Published

Since last week, more than 1,000 Rohingya people displaced from Burma have been camping in the Indian capital, Delhi, seeking refugee status from the UN refugee agency. Over the years, thousands of Rohingyas - a Muslim minority group in Burma - have fled to India to escape persecution. Avinash Dutt of the BBC Hindi service speaks to some to them to find out about their problems.

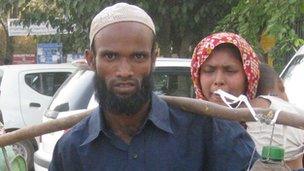

MOHAMMED ALAM

I live in Jammu in Indian-administered Kashmir along with my wife and seven children. To make ends meet, I deal in scrap plastic.

I had come to Delhi to seek refugee status from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), but we didn't get it. Now we are going back. Unlike in Burma, my life is safe in India, but there is nothing else.

Here, our children don't get admission in schools and we are not allowed to bury our dead in graveyards.

I believe if I have refugee status, my life will be better. If I have a refugee card, we would be entitled to some monthly allowances and our children would get to see school from the inside and our dead would become eligible for a grave.

Whatever happens, I will not go back to Burma. There they will imprison me or bury me alive.

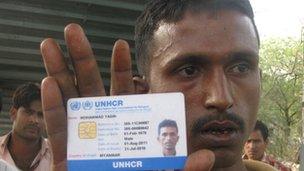

MOHAMMED YASIN

People talk about democratic reforms in Burma, about [opposition leader] Aung San Suu Kyi. But I tell them that we will go back to Burma when we feel that it is safe to return.

The military still rules Burma. You have to pay a tax on every egg that your hen lays. I fled Burma because I was asked to pay a large sum as tax to get married.

Here, you can move around till 10pm but in Burma you cannot venture out after 6pm. We cannot even stand in front of our homes.

In India, I have no identity so my 11-year-old son cannot get admission in a school. The asylum seeker card the UNHCR has given me is useless; it does not even bear my father's name.

If the UNHCR grants me refugee status, I will have a card that will have my father's name on it. My son will get admission in some school then.

MOHAMMED NOOR

My family used to own a cloth shop in Burma. Last year, I had a fight with the owner of an adjoining shop who is Buddhist. My entire family was attacked.

I ran away, crossed mountains and swam across a river to reach India.

I went to Calcutta first. There, I did some odd jobs, saved some money to reach Aligarh [in Uttar Pradesh] where I had heard that a few of my relatives lived. I don't know where the rest of my family is.

Like us, many non-Muslims have also fled Burma for India. Buddhists and other non-Muslims have been given refugee status here. So they get monetary assistance and other facilities, but because we are not recognised as refugees, we don't get anything.

I cannot think of going back to Burma. They will shoot me there. I still have bullet marks on my body.

MOHAMMED HAMID

In India, I have been living in Aligarh town for the last couple of years. The card that the UNHCR has given us is useless.

Many of the people who got refugee status earlier have gone abroad, many of them are getting monthly allowances.

I am told that if I get refugee status, I can get an identity card, I can get a passport as well.

Without the refugee status my life is very tough. If we get sick, we cannot get treatment in a government hospital unless we pay.

I ran away from Burma because I was not allowed to go to school or do the trade of my choice. Life here is not easy either, but it is safe.

MONTESERAT FEIXAS VIHE, UNHRC CHIEF OF MISSION

While Rohingya people are concerned about their security and safety in India, the government of India has assured us that they will not deport them.

On the basis of the asylum-seeker card issued by the UNHCR, the government has agreed to grant them long-stay visas.

The long-stay visas will give them a legal validity and will also entitle them to all the basic facilities like schooling and health.

We are totally satisfied with what the Indian government has done for them.

- Published12 April 2012