WW1: Can we really know the Lost Generation?

- Published

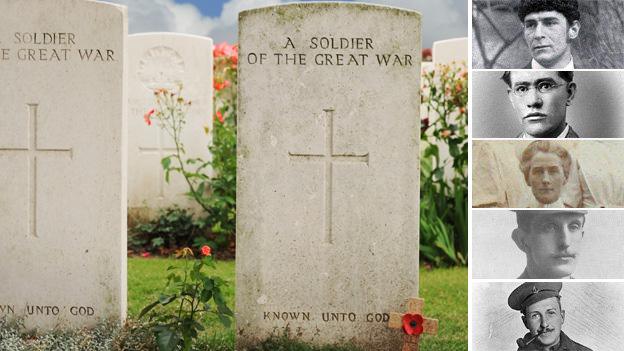

From top right: Franz Marc, Francis Ledwidge, Edith Cavell. Will Gladstone, Harold Chapin.

For the next four years, the world will commemorate the relentless power of death, and what is often called the Lost Generation.

But how should we comprehend that terrible collective encounter with death that was World War One? Perhaps the faces and stories of the individuals who died are needed, as well as the mind-numbing statistics.

Here are some who lost their lives in the conflict. Those lives were very different - but all were high achievers who seemed destined to make their mark even more strongly.

The war took Edith Cavell from relative obscurity to immortal fame. It took Harold Chapin and Will Gladstone, both quite well-known, now almost forgotten. It took Frank Ledwidge, just coming into his own as a poet and campaigner, and Franz Marc, already one of his country's leading artists.

It took more than 700,000 others from Britain alone.

Harold Chapin, 29, dramatist

Military rank: Lance Corporal, Royal Army Medical Corps

Died: Shot rescuing wounded at Battle of Loos, September 1915

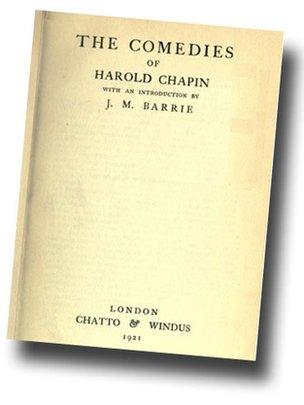

The author of Peter Pan wrote an introduction to Chapin's plays

In his 20s, Chapin had already written several acclaimed plays, compassionate one-act vignettes of life among the poor and struggling, and leisurely comedies that read like precursors of Private Lives.

When war started he immediately stopped writing and joined the Medical Corps.

He claimed he liked useful work that "does not involve going into the actual firing line". However, he spent most of his war in the dangerous role of stretcher-bearer, and doing it he died.

The author of Peter Pan wrote an introduction to an edition of Chapin's comedies published in 1921.

"He was still very young," wrote JM Barrie of Chapin, "and had... been getting his tools in good state for the bigger work he would have accomplished."

Chapin, he said, "would have returned from France... seeing life more clearly and more deeply" but "instead, he died a gallant soldier's death.

"He was probably the greatest 'might have been', so far as his particular art is concerned, that fell in the war."

Edith Cavell with trainee nurses at her Brussels school

Edith Cavell, 49, nurse

Matron, Belgian School for Nurses

Died: Shot for helping Allied soldiers escape, October 1915

London Hospital nurses laying wreaths at Edith Cavell memorial in Trafalgar Square (pictures: Cavell Nurses' Trust)

The pious daughter of a Norfolk vicar figures in the calendar of the Anglican Church as someone worthy of "commemoration". Her reported statement as she awaited execution that "Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone" has inspired generations since.

She was appointed to run Belgium's first nursing school in 1907, chosen because of her command of French and her own training at the London Hospital. As the war started the school was due to move into grander, purpose-built premises.

Hundreds of British and French soldiers caught behind enemy lines, and Belgians wishing to join their country's army, were helped by the network of which she was a part as they attempted to escape to Holland. Many she lodged in the nursing school itself; others she boarded out or helped in other ways.

Her execution aroused international fury and sparked a torrent of Allied propaganda. She confessed that she had broken German military law. But of scores of defendants at her trial, she was one of only two executed, and that just four days after sentence was passed.

Nick Miller, expert on the history of Edith Cavell, says of her: "The nursing world in Belgium was at her feet. She was the queen bee."

But he adds that if she had merely been imprisoned instead of executed "it's reasonable to surmise that nobody today would really recognise her much, certainly not in England; the Belgians might".

Francis Ledwidge, 29, Poet and Irish nationalist

Military rank: Lance Corporal, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers

Died: Killed by shell at battle of Passchendaele, July 1917

The writer John Drinkwater said: "To those who know what poetry is, the untimely death of Ledwidge is nothing but calamity."

Former miner, road ganger and union official, unlucky in love but with a growing reputation as a poet, Ledwidge joined up in 1916, surprising many who knew him. He wrote: "I joined the British army because she stood between Ireland and an enemy common to our civilisation." He fought at Gallipoli and in Serbia before going to the Western Front.

Francis Ledwidge's birthplace is now kept as a museum

He wrote more about country life in Ireland than about the war but sometimes combined the two:

It was too early for the lark/But the starry dark had tints of gold...

A bomb burst near me where I lay/I woke, 'twas day in Picardy.

He was severely shaken by the 1916 Easter Rising and the retaliation to it. He wrote an elegy for his friend, the executed Thomas MacDonagh, and remarked: "If the Germans came over the back wall, I wouldn't lift a finger to stop them." He hoped for a discharge from the Army, but would not desert.

The cottage where he was born near Slane, County Meath, is now kept in his memory as a museum. , external

Museum chairperson Rosemary Yore says of him: "His career was just coming into its own: he wrote in 1916 that his best was yet to come and that if he survived the war he would write great things.

"He would have been a major poet; he would have been up there with WB Yeats."

Franz Marc, 36, painter

Military rank: Lieutenant, Landwehr Artillery

Died: Killed by shrapnel near Verdun, March 1916

As WW1 approached, the paintings of the leading German expressionist Franz Marc became apparently chaotic, with the animals which he commonly depicted now caught up in the turmoil.

On the back of one, the Fate of the Animals, he wrote "All Being is Burning Sorrow" and later said it was a foreboding of war.

Yet Marc at first welcomed the conflict, writing: "The Augean Stables that is Europe can only be cleaned this way." He volunteered at the very start of the war.

Part of Fate of the Animals (1913) by Franz Marc - which he said could have been a premonition of war.

At the front, he prepared nine great painted awnings to disguise artillery positions from Allied aircraft. He called them his "nine Kandinskys" after his friend and fellow expressionist.

In 1916 the German authorities agreed that Marc and other leading artists could be more useful away from the front.

He wrote to his wife that the thought of coming home was too lovely to describe. He was killed the same afternoon.

The New Walk Gallery in Leicester has a famous collection of German expressionists, including works by Marc., external

"I'm sure that his fame would have rivalled Kandinsky," says its senior curator, Simon Lake. "His energy and output was prolific before the war, and his imagination was still active as his sketchbooks at the front testify.

"His depiction of animals in a spiritual and harmonious cosmos is really hard to beat.

"Certainly he would have exhibited internationally. He would have fallen foul of the Nazis and his work would have been declared degenerate."

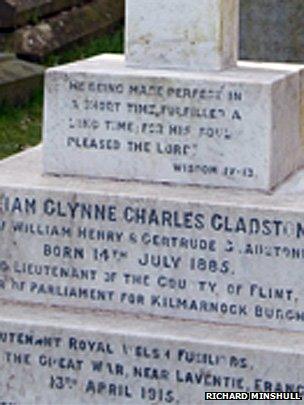

William GC Gladstone MP, 29

Military rank: Lieutenant, Royal Welch Fusiliers

Died: Shot in the head at Laventie, April 1915

Grandson of one of Britain's greatest prime ministers, president of the Oxford Union, MP at 26, Lord Lieutenant of Flintshire and squire of the great estate of Hawarden; no-one doubted that Will Gladstone was destined for a life spent among the leaders of his country.

But he had no illusions about his talents as a soldier.

"I have no natural aptitude for it, and what is more, no training of any sort," he wrote to the military authorities.

Will Gladstone's body was brought back to Hawarden for burial. It was a village funeral but "a national event"

As war between the continental powers loomed, Gladstone was positive that Britain should stay out of it. "Let them fight it out by themselves," he said in a speech on 3 August. This hope was shattered by the German invasion of Belgium.

He said he wanted to enlist as a private, since he dreaded bearing any responsibility he was not fit for, but was advised that he had to be an officer.

He died while trying to locate a sniper, though he had been warned that his height put him at particular risk.

Former chief scout Sir William Gladstone is Will's successor as squire of Hawarden today.

"I think he would have slipped into the top flight quite easily in Parliament," he says of his kinsman. "It's a most remarkable career in a way because he was a very modest and self-effacing person by nature."

Will was one of the very few soldiers killed on the Western Front whose body was brought home, Sir William points out. Will's burial in Hawarden churchyard was "only a village funeral, but it was quite a national event and the fact that it was an actual funeral certainly enhanced the feeling of loss locally".

Find out more about the centenary of the outbreak of World War One at BBC Online