Disconnected generation ready to make Westminster pay

- Published

- comments

Many voters want to vote for "none of the above"

The ferry across the Thames ploughed a steady path, backwards and forwards, Essex to Kent, Kent to Essex, a soporific early-morning ride.

But politics, here and across the world, is perhaps moving outside familiar currents, into choppy waters, leaving mainstream politicians unsure if they are waving or drowning at the voters.

Take my fellow passengers, as I stuck a microphone underneath their noses and asked political questions that no reasonable person would want to answer before breakfast.

But most wanted to have their say, and it wasn't always what I expected.

I was braced for some pithy comments about senior politicians, but hardly what came: one was described to me as a "Marxist Zionist war criminal", even though the individual concerned is none of these things.

These three men - who described themselves as "nationalists" - didn't like anyone else any better. Politicians were all the same, in it for themselves, and they wouldn't vote for any ever again. Well, maybe UKIP. But probably not.

Three other passengers declared that they had never voted and never would.

Four middle-aged women said they were Labour - "father was always Labour, so am I" - but quickly added that they are all the same: "In it for themselves, and take a third of your money."

Distrust of politicians

A scientific, judiciously balanced opinion poll this was not. Still, my trip to Gravesend captured a certain mood.

There was a deep distrust of politicians, a distaste for them that bewilders those in Westminster.

It was as if the Age of Insecurity met the Death of Deference and they had a child, born swaddled in contempt - I christen it The Disconnect.

Westminster is struggling with a poor reputation

It is one of the underlying stories of our age, and I intend to bang on about it quite a bit, in these columns and on The World This Weekend.

In the UK, two events have forced politicians to look voters in the eye.

One was the Scottish referendum, a close shave with the end of a nation.

It also gave the Scottish National Party more prominence, more members and soon more power.

And in the south of England it is the rise of UKIP that has forced Team Westminster to examine what the future might hold.

It is a situation that has been reflected by events in the US. The Tea Party, which is not a party, but a hydra-headed movement of like-minded malcontents, loathes Obama, but doesn't have much time for many Republicans either.

Supporters have a hearty distaste for Washington's ways, for Washington professional politicians, and are careful to call themselves Conservatives rather than Republicans. They talk of "taking our country back".

Even as the Republicans were in the middle of winning a stunning victory in this week's mid-terms, one leading Tea Party activist, Erick Erickson, was writing, external: "In 2014, the American public has shown that it hates Washington DC, and the Republican leaders in Washington are demonstrating why."

He added: "Many of those GOP (Grand Old Party = Republican) Senate candidates who squeaked into office are, in my view, political philanderers - by which I mean that while they pledge their troth to conservative principles, they still carry on outrageous affairs with Big Government."

Far right

In Europe the far right are on the march. They have increased their vote, most recently in Sweden.

But it is France that worries many in the political centre, not only in Paris, but even more in Brussels and Berlin.

They see a real possibility of President Marine Le Pen in the Elysee Palace in 2017 - the National Front at the heart of Europe.

Neither the Tea Party nor UKIP share these parties' fascist roots and they both passionately reject any suggestion of racism.

So I am in no way suggesting all these movements are identical.

But there is little doubt their voters' discontents are similar: the sense of a world that is changing too fast, that is slipping though their grasp.

They would all find solace in the Tea Party cry "take our country back" without wanting to spell out from what or whom.

The seminal book on UKIP, Revolt on the Right,, external identifies many supporters as "the left behind": older, poorly educated, poorly paid.

Partly this is a reaction to the global financial crisis, and globalism itself.

There are winners as well as losers and even as the the banks and the rich bounce back, others see no sign of recovery.

While an elite feel as comfortable in Boston or Birmingham, Berlin or Beijing, those left behind on the runway may find solace in a closer, and older, identity.

Protectionism and closed borders seem attractive ways of shutting out the threatening world.

This is part of the tale, but not the whole story.

The leaders of UKIP and the Tea Party whom I know are hardly poor and unskilled. Many are well-heeled, and well-educated.

While there is no doubt the main beneficiaries of The Disconnect are on the right, some parties on the left are growing too.

The Greens say they now have 20,000 members, the SNP boast of their increase, external while the Left party in Germany is the fourth largest in parliament and new movements are doing well in Spain and Greece.

Still, many mainstream politicians don't get it.

Patronising the voter

Here's a test. How many times after the Rochester by-election will you hear the term "protest vote"?

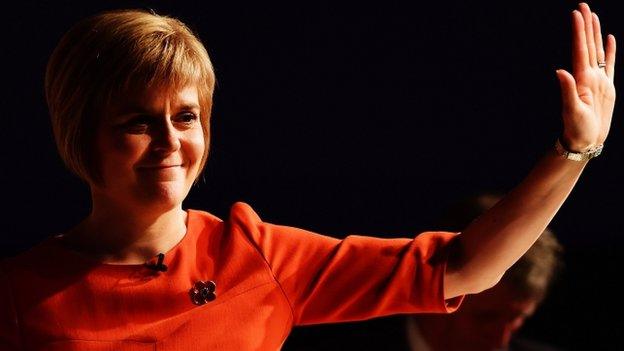

Nicola Sturgeon's SNP has seen a surge of support

It is a term banned from my personal lexicon. Of course people do vote differently in by-elections from general elections, when, in effect, they are choosing a prime minister.

But the idea that a vote is a mere protest underscores a profound disrespect for voters by the media and the main parties.

They look on voters as if they were a petulant five-year-old, who marches out the door clutching a teddy bear and one T-shirt, declaring that she's leaving home.

Indulgently, the parental parties look on, knowing she will be back long before teatime - indeed before she gets to the end of the road.

Likewise the parties think "their" voters will have their little strop over a war or a failed economy and return to a proper way of doing things, voting for one main party or another - or daringly perhaps a third - come the general election.

It hasn't dawned on them that the conventional way of voting may be what you could call an "under protest vote" - the least worst choice of those who might form a government - that may not reflect what they really want or believe.

The economic crisis has left a sour taste towards the parties who take turns in taking power.

In France, a disliked centre-right government has been replaced by an even more unpopular socialist one.

In the US, Obama, elected on a wave of hope, was elected again in 2012 but given a kicking in 2010 and an even more profound beating this week.

In the UK, an unpopular Labour government has been replaced by a coalition that has failed to win hearts and minds.

In short, all over the world, people want to scrawl on their ballot paper "none of the above".

I wonder how much this is because politics is disconnected from the world of choice we live in.

I could pause in my writing and take two minutes to choose a bewildering array of electronics, or exotic fruit or styles of shirts at the click of a trackpad.

Or I could take a break and pop down the road and order a skinny flat white, an espresso or an americano, some with or without chocolate or froth.

But my political choice extends to going to a local school every five years and choosing an often ideologically incoherent bundle of policies and then sitting back and watching for another five years.

Some in the main parties are very worried by all this implies.

There will be a hunt for solutions before the election.

Because it is beginning to dawn that the little five-year-old who'll be back repentant in time for tea has grown up, moved out, bought her own flat and is looking for others to love.

"There'll always be a room for you here," the parties will insist.

The next few months will show if it is too late for that.