Eurozone prepares for QE

- Published

The eurozone, it is widely thought, is about to get a dose of a new economic medicine.

The European Central Bank is expected to announce this week that it's going to go into the financial markets to buy substantial amounts of government debt using newly created money - a policy known as quantitative easing, or QE.

There has been mounting speculation that the ECB is preparing to act along these lines, and there will be serious disappointment in financial markets if that does not happen.

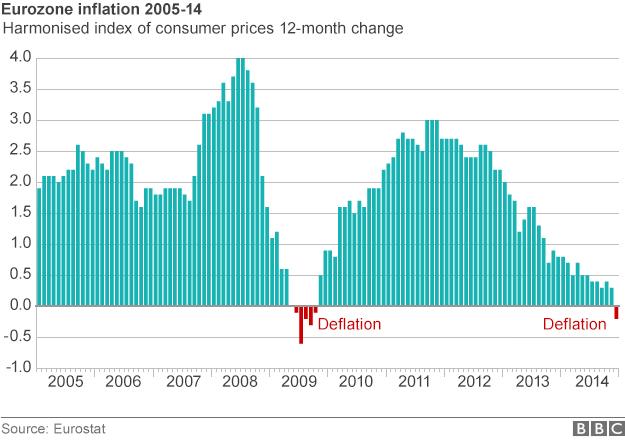

The problem the ECB wants to tackle is inflation that is too low. Indeed last month it turned into deflation, or falling prices.

Deflation is partly a symptom of the eurozone's persistent economic weakness. But it could also aggravate it.

Deflation tends to be bad for debtors. The problem is that their incomes may fall, but their debt payments - if they debt involves fixed interest rates - may not.

With governments, falling prices and incomes will hit revenue from income tax and VAT. Most of their debt payments are at fixed rates.

'Unambiguously positive'

There have been warnings that deflation could reignite the eurozone's debt crisis.

ECB President Mario Draghi has welcomed falling oil prices

The London economic consultancy Capital Economics has said: "There is a clear danger of a more sustained period of deflation, which would destroy peripheral countries' debt consolidation efforts, and could cause market concerns to once again spread from Greece."

Now it is true that the eurozone had a period of deflation back in 2009. It lasted five months. But Capital Economics reckons the recent fall in energy prices could keep the eurozone in deflation territory for a lot longer this time.

But if it's the result of cheaper energy, you might argue, then it's surely not a problem.

There is a lot in that view. The International Monetary Fund's chief economist Olivier Blanchard said in a BBC interview that the oil price fall is "what I hate to call a gift of God" for the eurozone.

He said it means there has been "a very large increase in real [that is inflation adjusted] incomes of people, and is therefore likely to lead to more spending."

The ECB President Mario Draghi has described the direct impact of cheaper oil as "unambiguously positive", external.

The fall in petrol and diesel prices has left people with more money in their pockets

Even so, Mr Blanchard says that deflation is worrisome.

What bothers Mr Draghi is what he called "second round" effects, that falling prices might become "embedded in inflation expectations", and could affect wages as well as the prices of other types of goods.

In any event, it's worth noting that inflation excluding energy prices was 0.6% in December, a good deal lower than the ECB's target of below but close to 2%.

So that's what Mario Draghi and his colleagues in the ECB's policy-making committee are worried about.

Overseas examples

Quantitative easing is on their agenda because the traditional ammunition for a central bank is spent.

The ECB's interest rate policy is just about zero. The main rate that it charges for lending money to the commercial banks is just 0.05%. And the rate it pays them for holding their surplus finds overnight is below zero - minus 0.2%.

The markets have expected the ECB to announce a period of quantitative easing

In similar circumstances, central banks in the US, UK, and Japan, wanting to provide more stimulus have gone down the path of quantitative easing, QE.

QE history

Three major developed country central banks have carried out QE in recent years: the US, the UK and Japan.

In the US and UK it started in the aftermath of the financial crisis. The American move, worth a total of about $3.5tn (£2.3tn), has coincided with a recovery from a nasty recession.

In the UK the return of convincing growth came only a few years after the active asset purchases of £375bn came to an end, though to this day the Bank of England still holds them.

Japan started QE much earlier, back in 2001, and its cumulative scale is in the region of $1.7tn or so. It's an attempt to deal with prolonged economic weakness. Despite the effort, Japanese growth has never really decisively resumed.

The evidence from these experiments is inconclusive. Some say the US and UK would have recovered without QE. Others say Japan would have been in worse shape without it.

And that's what is widely expected from the ECB - that it will announce a plan to buy substantial volumes of government debt using newly created money.

The ECB has, over the course of the financial crisis, done things that have elements in common with this. It has bought the bonds, the debts of some governments, and it has also bought assets backed by loans to the private sector.

With much of this, though not all, the ECB took steps to offset the additional money creation involved in buying these assets. The technical term is sterilisation.

In addition, the asset buying undertaken by the ECB so far was aimed at improving conditions in specific parts of the eurozone financial system: the availability of credit to the private sector,, external and the periods of very high borrowing costs in some countries, external.

What we are expected to get this week is different in that it won't be quite so focussed - the aim will be to generate higher inflation across the eurozone. And the scale is likely to be bigger than we have seen before.

The figure often suggested that the ECB will spead on QE is 500bn euros ($591bn; £382bn). That's smaller than the programmes undertaken by central banks in the US or Japan, and the UK, in comparison with the size of the economy. But then all those QE programmes did take time to build up to their full scale.

'Hyperinflation phobia'

So how would it work? Buying bonds in large quantities can raise their price, which lowers the return on them.

The return on bonds is in effect an interest rate, so the idea is that QE should exert downward pressure on interest rates throughout the economy, , externaleven when the central bank's own interest rate policy can no longer do that.

Germany is fearful of high inflation

So the idea is that QE leads businesses to want to invest more and consumers to spend. The additional demand for goods and services would then push inflation up too, and reduce the risk of aggravating the eurozone's persistent debt problems.

In addition QE can weaken a currency on the foreign exchanges. The fact that the policy tends to drive down interest rates also makes investors less enthusiastic about investing in the currency. The weaker currency makes business more competitive against rivals outside the eurozone.

The IMF's Olivier Blanchard told the BBC that the recent depreciation of the euro is "largely due to anticipation of QE coming down the line".

Now there are plenty of critics of QE. In the US a group of them wrote an open letter to the then Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, external, published in the Wall Street journal, warning of a risk of excessively high inflation.

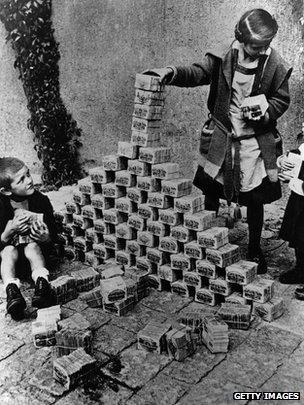

Some in Europe, especially Germany, share that concern. There is history behind that, the hyperinflation of 1923 in Weimar Germany, which was followed in the next decade by the rise of the Nazis.

The Economist has called it "Germany's hyperinflation phobia, external" and as the paper points out there is a debate to be had about exactly what were the economic factors behind the disaster that followed in the 1930s.

Still, it is an issue in German politics and it has made it harder for the ECB to embark on a policy that can be characterised as "printing money".

There is also a concern that by buying government debt, the ECB would be relieving the pressure on countries that arguably need to do more to reduce their debts and reform their economies. And if any of those governments were to default, the argument goes, it would be taxpayers across the eurozone that would have to foot the bill.

There have been reports that the ECB will address the latter concern by having national central banks in the 19 member countries of the eurozone buy the bonds and take responsibility for any losses there might be - which would almost certainly let the German taxpayer off the hook.

It has been a long wait. The eurozone is, probably, about to embark on something that the US, Japan and Britain started years ago.

And nobody seems to think it will fix all the eurozone's problems. The best that eurozone QE might achieve is to alleviate one factor that could make them worse.

As the BBC's Economics Editor Robert Peston put it - "painkillers to an economy that needs rather more radical structural treatment".

- Published20 January 2015

- Published14 January 2015

- Published8 January 2015

- Published7 January 2015