'I hated myself for Abu Ghraib abuse'

- Published

Gina Haspel has paved the way for her confirmation as new CIA director, after repudiating torture tactics used in the past. But the scars from one of America's darkest chapters, the abuse of Iraqis at Abu Ghraib prison, still linger, as one of the men involved explains.

A big, bear-sized man, Jeremy Sivits hunches his shoulders when he walks across the car park of a pizzeria in Martinsburg, Pennsylvania, trying to make himself smaller.

He shoves his hands in his pockets as he stands next to me, outside where we can speak freely about the cruelty of his past, without fear of being overheard.

The Abu Ghraib scandal broke on 28 April 2004 when photos taken by him and other soldiers at the prison were revealed on CBS News.

The pictures showed naked prisoners heaped into a pyramid, forced to simulate sexual acts and adopt humiliating poses.

One showed a US soldier, Lynndie England, holding a prisoner on a strap made to look like a leash. Another, the defining image of the scandal, showed a hooded man standing on a box and holding electrical wires.

Sivits was sentenced to a year in prison for dereliction of duty, for counts related to taking a picture and failing to stop the mistreatment of detainees.

In the car park, he describes lessons he's learned from the scandal - about humility, compassion and doing the right thing.

Sivits looked for work in Martinsburg, where he lived after serving time in prison

As cars roar past, we duck inside the restaurant and find a quiet place. He says he believes his own personal lessons have also been absorbed by the nation.

Like many of those who worked at Abu Ghraib and became embroiled in the scandal, Sivits comes from a rural part of the country that offered few prospects for young people.

Sivits grew up in Hyndman, Pennsylvania. It is located in the "valley of nowhere", says one local, Robert Clites.

The 69-year-old says there is no mobile phone coverage for a six- to 10-mile radius. The main street smells of diesel and sawdust from logging trucks that careen through town.

Sivits' old house, right next to the train tracks, is now charred from a fire and lies vacant with boarded-up windows.

His mother, Freda, worked at Dollar General, a discount retailer. Father Daniel, a drywall finisher, completed two tours in Vietnam and received two combat medals.

Daniel died last year of lung cancer, and family members said in an obituary that rather than buying flowers, mourners could instead give money to Freda to help pay for the funeral.

A Hyndman native, Robert Clites remembers Sivits as a "courteous kid"

At Hyndman Senior High School, Sivits was known for his polite manner and his eagerness to help out.

"He was a courteous kid," says Clites, sitting in a supermarket delicatessen in Hyndman. "Someone would ask him to do something, and he'd do it. And whatever consequences there were, well, that's what it is."

"A nice young man," says Herman Rawlings, 86, a Korean war veteran who was sorting through his mail in the post office. He believes Sivits was following orders in Iraq and the punishment was unfair.

"He got a raw deal. When you're in a position like he was in, you do what you have to do."

Rawlings gives me a hard stare and says: "Hell, war is hell."

Sivits, 38, has sideburns and short, brown hair and speaks with an accent that hints at his Appalachian roots. He says that as a child he dreamed of being a soldier like his father.

"When I was 18, I enlisted and started my adventure," he says. He became a member of the 800th military police brigade, and in 2003 he was sent to Iraq.

"I thought: 'Man, I'm going to a big sandbox,'" he says and smiles.

More from Tara:

Not long after Sivits arrived in Iraq, he was assigned to work at Abu Ghraib, a prison in Baghdad where he filled in as a mechanic and a driver.

At the time about 2,000 Iraqi men, women and children were held at the prison. Many were innocent and knew nothing about the insurgency - they'd been picked up accidentally in raids.

By this time, the US had approved the use of harsh interrogation methods at US-run detention facilities. Vice-President Dick Cheney said shortly after the 9/11 attacks that they would work the "dark side".

With that goal in mind, Washington officials recast laws in order to allow for interrogation methods that had long been defined as torture, and the techniques were used on prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

Detainees were beaten - some to death. One photograph shows the corpse of a prisoner, Manadel al-Jamadi, who had been held there by the CIA. His body was wrapped in plastic.

Charles Graner, centre, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for his role in the abuse

Standing in the pizzeria, Sivits describes the events that he witnessed at the prison.

One evening in November 2003, he helped a guard he says was known as "Freddie" - Ivan Frederick - to escort detainees to Tier 1A, a cellblock for dangerous prisoners.

After they got there, they saw naked prisoners lying in a hallway, jumbled together. Charles Graner, Lynndie England and other soldiers were standing around, laughing. Frederick and Sivits placed their men onto the heap.

"Everybody's like: 'Well, why didn't you do this? Why didn't you do that?'" Sivits says. "It just happens and happens. You lose track of time, and it's like you're in a big warp."

More on Abu Ghraib

Photographing former prisoners at Abu Ghraib

In the midst of the cacophony, Sivits noticed that the "flex cuffs", as military handcuffs are known, were bound too tightly on one prisoner, causing his hands to swell and turn purple.

Sivits turned to Graner and said: "Dude, this guy's going to lose his hands." He pulled out a multi-tool and slid a blade under the prisoner's handcuffs and loosened them. Afterwards, Sivits tells me, the prisoner relaxed: "His hands - you could see the blood flow started back."

Graner handed Sivits a camera and crouched next to a hooded man in an orange jumpsuit who was crumpled on the floor. With one hand, Graner held the prisoner's head gently. Graner balled his other hand into a fist.

"He had his head cradled," Sivits says, describing the way that Graner held the prisoner and posed for the camera. Sivits took a picture.

Then Graner punched him, says Sivits. "Don't know why." He lets out a short laugh. Then he sighs.

At the prison, Lynndie England held a detainee on a leash

"That was the only picture I took," says Sivits. "I was there - kind of." He looks into the distance when he talks about what happened at the prison. He has a detached manner, as if someone else - not him - was there that night.

When the Abu Ghraib photos appeared on television the following spring, President George W Bush said: "We will learn all the facts and determine the full extent of these abuses. Those involved will be identified. They will answer for their actions."

Sivits and 10 other soldiers were convicted for the abuse. Graner was sentenced to 10 years, Frederick to eight, and England to three.

The trials laid bare the crimes and the messy, intertwined lives of the soldiers. After being released from prison, England moved back to her hometown, Fort Ashby, West Virginia. She's now living with her parents and taking care of her child, the son of Graner. While Graner was in prison, he married Megan Ambuhl, another one of the convicted soldiers.

After the scandal broke, the US lost the moral high ground, according to many of those who fought in the war. Insurgents who attacked US forces after 2004, according to a retired general, Stanley McChrystal, said they were enraged by the Abu Ghraib photos.

Abu Ghraib image used by protesters in Baghdad

The prison was handed over to Iraqi authorities in 2006, and eight years later the place was closed down. Several dozen former prisoners sued a private contractor, a company that employed Arabic-language interpreters, for their role in the abuse. A settlement of about $5m (£3.7m) was reached in 2013.

One of their lawyers, Shereef Akeel, says the settlement provided "a huge sense of justice".

After prison in Kuwait, Germany and North Carolina, Sivits went back to Pennsylvania. "I was a nasty person for a long time because I had so much hatred inside of me - for myself."

He could not find a job as a mechanic so he began to counsel people who were addicted to drugs and alcohol. "I decided that I was going to use my experience from Abu Ghraib to talk to them about making choices."

He spoke to them about mistakes that he'd made during the war, ones he deeply regretted.

"What happened at the prison was a horrible thing," says Sivits

"I'm like: 'Yeah. That was me. That isn't who I am today. I'm a different person.'"

"What happened at the prison was a horrible thing," he adds. "But I think people have learned a little." He found a kind of redemption through counselling work and has been able to move forward with his life.

Yet his efforts to help people in Pennsylvania and atone for his past offer little solace to those who were subjected to the abuse at the prison.

After the scandal, Ali al-Qaisi posed for a formal portrait of himself

Many of them say they're still feeling the effects of their injuries. Ali al-Qaisi, who became known as the "hooded man" (the name refers to the image of a hooded prisoner standing on a box), said in a video posted on Twitter, external: "It crushed our psyches."

Sivits is right that the country did change after Abu Ghraib.

Torture was banned in 2009, shortly after President Barack Obama took office. Military interrogations were restricted and "black site" prisons, CIA-run facilities where detainees were subjected to harsh interrogations, shut down.

A new legal framework was created so that perpetrators, whether they worked for the government or a military contractor, could be more easily held accountable.

Yet human-rights advocates say that despite the changes in law and government policy, people are now more accepting of the idea of torture than they were in the past.

The Abu Ghraib photos were shocking but over time outrage faded.

Despite widespread rejection of those images, a "disturbing number" of voters later said yes when asked if torture was ever justified, says Katherine Hawkins, an investigator who works for the Project on Government Oversight. One recent poll suggests two-thirds of Americans think torture can be justified., external

She and others believe that Abu Ghraib is more than a dark chapter in the nation's past.

"The use of torture wasn't relegated to history," says Alberto Mora, who served as the Navy's general counsel during the Bush administration.

"It continues to resonate."

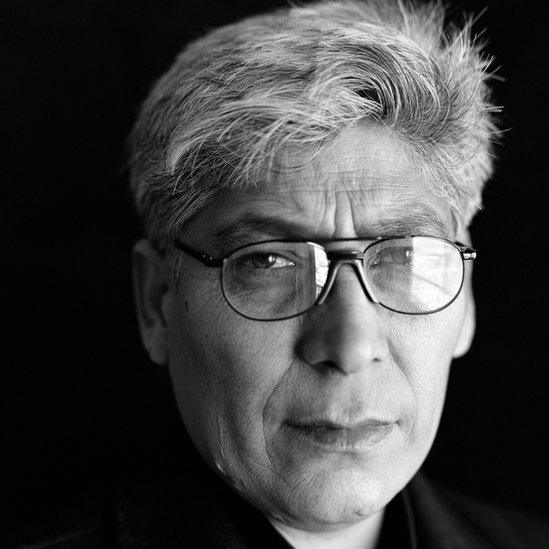

Alberto Mora tried to stop the harsh interrogation programme - and torture

During the 2016 campaign, Donald Trump said that if he were elected president he would bring back waterboarding, an interrogation technique that's banned by federal law, as well as methods that were "a hell of a lot worse" than waterboarding.

He shifted his position after the election, saying he would defer to Defence Secretary James Mattis, who has said torture was a bad idea.

But the new national security adviser, John Bolton, has previously said that Americans should have the full range of interrogation methods, external available to them - and that he's open to the possibility of waterboarding in order to get information from someone.

Trump's nominee for CIA director, Gina Haspel, once oversaw a black site, and human-rights activists say she is not suitable for the role of director because of her role in the harsh interrogation programme under the Bush administration.

Haspel: 'I would never take CIA back to interrogation programme'

"In these very dangerous times, we have the most qualified person, a woman, who Democrats want OUT because she is too tough on terror," the president has tweeted, external. "Win Gina!"

She said during her confirmation process she would not re-start the harsh interrogation programme and conceded it was wrong. But it will likely not stop her being confirmed later this month.

Nearly a decade and a half after the scandal, Mora says he's not sure people in the US have learned lessons in humility, the kind that Sivits describes.

Mora reminds me that the president and many political leaders say that they support the use of torture.

The laws against torture remain in place. But Mora says he worries that if Americans engage in another full-scale war like the one in Iraq, they'll resort to torture again.

"This is what Abu Ghraib represents," he says. "It represents the possibility of making a mistake and returning to the use of cruelty."