Coronavirus: Fake cures in Latin America’s deadly outbreak

- Published

Brazil has the second highest number of coronavirus cases in the world

Latin America is battling some of the world's most devastating coronavirus outbreaks, and is also facing the scourge of fake cures and unproven treatments promoted on social media across the region.

In the week when Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro tested positive for Covid-19, we've debunked some of these misleading claims.

A video of Mr Bolsonaro taking the drug hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for his illness has clocked up six million views on Facebook.

We've previously looked into the controversy surrounding the drug and the lack of evidence for its effectiveness in the treatment of patients with Covid-19.

While admitting that the drug had not been scientifically proven, Mr Bolsonaro said "with all certainty" that it was working for him, and that he was feeling better.

The anti-malarial drug received global attention when US President Donald Trump endorsed it both as a preventative measure - he took it himself for a while - and as a treatment for the disease.

A video of President Bolsonaro taking hydroxychloroquine has clocked six million views on Facebook

Brazilian fake Facebook accounts

This week Facebook took down what it described as a network of fake accounts linked to employees of President Bolsonaro's government, as well as the president's sons Eduardo and Flávio.

These accounts had promoted misleading and fake news about the coronavirus, such as claiming the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment, and that the Covid-19 pandemic was being exaggerated.

Flávio Bolsonaro, a Brazilian senator, said it was possible to find thousands of profiles supporting the Bolsonaro government, and to his knowledge "they are all free and independent".

One of the removed Instagram accounts, called @bolsonaronewsss, was run anonymously, but researchers from the international think-tank the Atlantic Council, external found registration information on the page confirming it was linked to Bolsonaro's special adviser Tercio Arnaud.

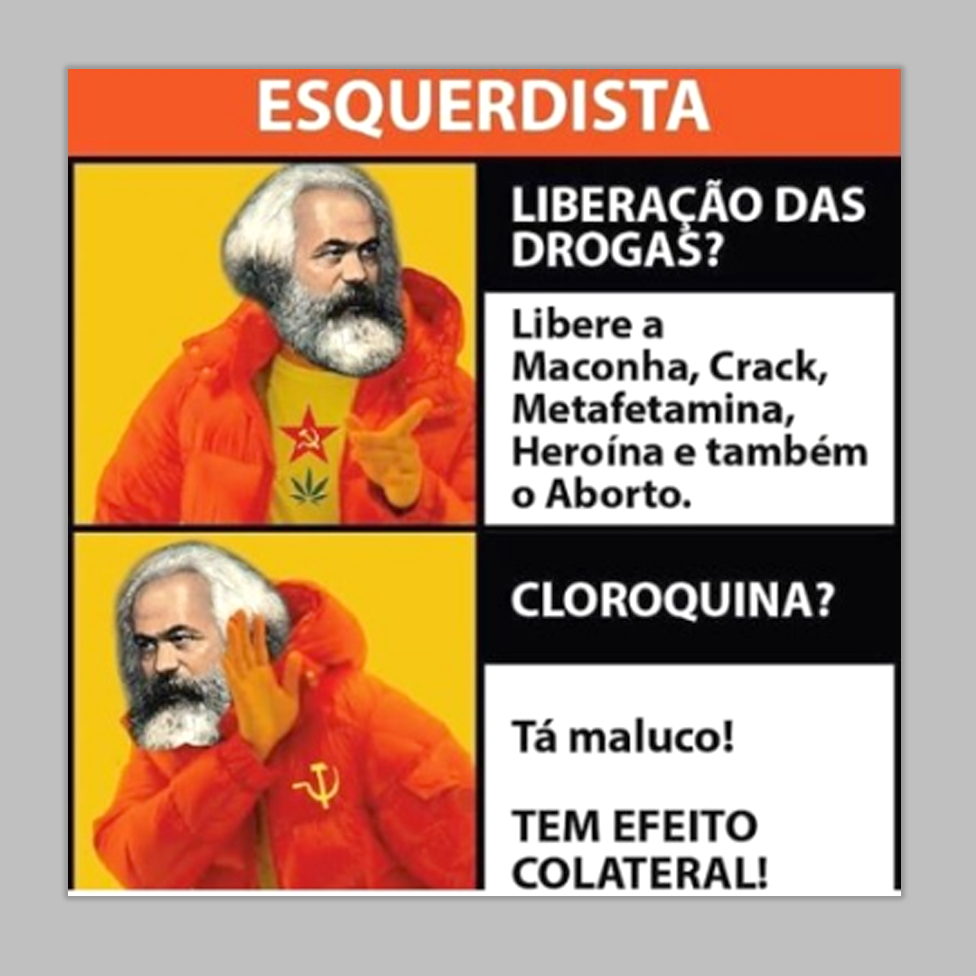

The pro-Bolsonaro network has posted attacks on "leftists" and promoted unproven cures across Instagram and Facebook

The BBC has attempted to contact Tercio Arnaud for comment, but has not received a reply.

"Political polarisation here in Brazil has captured the debate about the pandemic" says Sérgio Lüdtke, Editor of Comprova, a Brazilian fact-checking project.

He says supporters of President Bolsonaro have adopted certain themes online, including the defence of the effectiveness of unproven medicines such as hydroxychloroquine.

Comprova has been fact-checking widely-shared claims on social media and messaging apps about the pandemic. Four out of ten of these checks since the end of March were related in some way to unproven drug treatments.

Fake 'miracle cure' has not been approved

At the end of June, a Facebook post claimed: "The Bolivian Ministry of Health approved the use of chlorine dioxide". The post has been shared thousands of times across Latin America.

But the post is fake, and officially denied by the Bolivian government.

Chlorine dioxide is a bleaching agent found in a substance claiming to cure a range of illnesses often advertised as "miracle mineral supplement", or MMS. ' There is no evidence it works and health authorities say it's potentially harmful.

You don't have to look very hard to find it being promoted on social media. We found Facebook groups created in the last two or three months in Peru, Bolivia, Colombia and Argentina, with thousands of followers promoting or even claiming to sell MMS.

Regional authorities have seen an increasing number of poisonings due to improper use of chemical products used as disinfectants, says The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

The body says there have even been cases of health professionals promoting the use of chlorine dioxide solution.

In June a doctor in Peru in charge of his region's Covid-19 response was fired, after calling for chlorine dioxide to be distributed to everyone with coronavirus symptoms.

Unproven drug being widely sold in Latin America

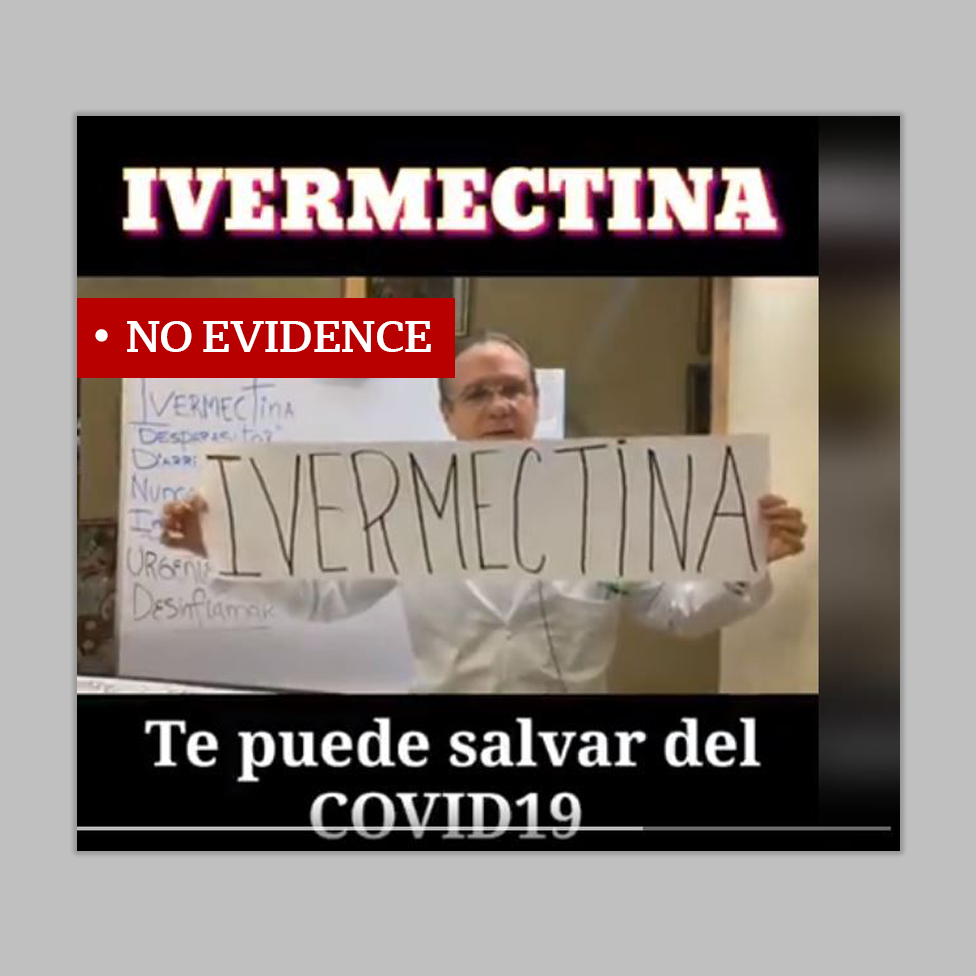

There's been surging interest in Latin America in a drug called ivermectin, approved for use against parasitic worms, to treat or prevent coronavirus, despite the lack of evidence.

A video posted by a Bolivian account labelled "Ivermectin can save you from Covid-19" featuring a Mexican pastor, has been shared 285,000 times and continues to circulate on Facebook.

Along with many other drugs, ivermectin's effectiveness against Covid is being evaluated in clinical trials.

But the PAHO has said studies so far "were found to have a high risk of bias, very low certainty of the evidence, and that the existing evidence is insufficient to draw a conclusion on benefits and harms.", external

Ivermectin "is incorrectly being used for the treatment of Covid-19" says the PAHO, "without any scientific evidence of its efficacy and safety for the treatment of this disease".

Despite this, health officials in Peru, Bolivia and parts of Brazil have endorsed and administered the drug - and it has been widely sold.

"In the case of ivermectin, all corners have been cut", says Dr Carlos Chaccour, Assistant Research Professor at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health.

"A combination of doctors and governments legitimately desperate to help" he says "plus the particular abundance of ivermectin in Latin America, help to explain why the drug has been so popular."

Warnings have also been issued about the risks of a version of the drug designed for animals not humans, external that could do serious harm, which is being sold on the black market.

An association of doctors in Colombia has raised concerns about people self-medicating at home

Concerns about self-medication

By Luis Fajardo, BBC Monitoring

It is an ongoing source of concern for public health authorities in Latin American that bad advice is being given to the public to self-medicate with unproven treatments in both traditional and social media.

People across the region are also being confronted by seemingly contradictory messages from official sources.

As Latin American countries face a growing threat from the pandemic, and with desperation growing at the rising death toll, it's perhaps not surprising the demand for "miracle cures" and simple, "do-it-yourself" remedies has been so high.

These claims are appearing not only in fringe social media groups but also - in some cases - on mainstream national media outlets.

Additional reporting by Juliana Gragnani, Olga Robinson and Shayan Sardarizadeh.