Coronavirus and hydroxychloroquine: What do we know?

- Published

There are doubts about its effectiveness as a treatment

There's been widespread interest in hydroxychloroquine as both a preventative measure and for treating patients with coronavirus.

President Trump has used it as a preventative measure, and President Bolsonaro of Brazil has also taken it.

But despite some early studies raising hopes, one subsequent larger scale trial has shown it's not effective as a treatment.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has halted its trials, saying that the drug doesn't reduce death rates in patients with coronavirus.

What is hydroxychloroquine for?

Hydroxychloroquine has long been used to treat malaria as well as other conditions such as lupus and arthritis.

It's used to reduce fever and inflammation, and the hope has been that it can also inhibit the virus that causes Covid-19.

Some early studies showed that it may be able to shorten the duration of symptoms experienced by coronavirus patients, while others indicated it had no positive effect at all.

One of the world's largest studies - the Recovery trial run by Oxford University - has involved 11,000 patients with coronavirus in hospitals across the UK and included testing hydroxychloroquine's effectiveness against the disease, along with other potential treatments.

It concluded that "there is no beneficial effect of hydroxychloroquine in patients hospitalised with Covid-19" and the drug has now been pulled from the trial.

There's been some hope that hydroxychloroquine could be effective if used early on when a person gets the virus, before there's a need for them to be hospitalised.

However, there's no clear evidence on this and the jury is very much out as to its effectiveness in the early stages of infection.

There are in fact overall more than 200 trials currently underway around the world on its impact either as a prophylactic or treatment for Covid-19.

Why have the drugs become so controversial?

Promotion by leading political figures such as President Trump has led to both hydroxychloroquine, and the related drug chloroquine, becoming the subject of widespread speculation online about their potential benefits and harmful effects.

This has led to high demand for the drugs and global supply shortages.

There's also been controversy within the scientific community.

American scientists have begun a trial to see if chloroquine will help treat coronavirus

Trials around the world were temporarily derailed when a study published in The Lancet claimed the drug increased fatalities and heart problems in some patients.

The results prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) and others to halt trials over safety concerns.

However, the Lancet subsequently retracted the study when it was found to have serious shortcomings and the WHO resumed its trials.

Other studies have looked at using the drugs as a preventative measure against Covid-19.

The Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU) is conducting mass clinical trials and has enrolled 40,000 frontline workers in Europe, Africa, Asia and South America, giving participants either chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine or a placebo.

Professor Sir Nick White, who's leading the trial, said: "Most experts agree there is a much better chance of benefit in prevention than treatment."

This study is able to resume after being placed on hold following the fallout from The Lancet's retracted study.

There haven't yet been results from this or other ongoing randomised studies on the drugs as a preventative treatment.

What are the side-effects of hydroxychloroquine?

A number of countries have authorised the hospital use of hydroxychloroquine or its use in clinical studies under the supervision of healthcare professionals.

In March the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted "emergency use" authorisation for these drugs in the treatment of Covid-19 for a limited number of hospitalised cases.

But the FDA subsequently issued a warning about the risk, external of the drugs causing serious heart rhythm problems in coronavirus patients and cautioned against using them outside of a hospital setting or clinical trial.

And in June, the FDA withdrew the drug., saying clinical trials had shown it was no longer reasonable to believe it would produce an antiviral effect.

There have also been reports of people poisoning themselves taking the drugs without medical supervision.

The WHO has responded by advising people not to self-medicate and "has cautioned against physicians and medical associations recommending or administering these unproven treatments."

France had authorised hospitals to prescribe the drugs for patients with Covid-19 but later reversed that decision after the country's medical watchdog warned of possible side effects.

Why have these drugs gained such prominence?

President Trump took the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine as a preventative measure against Covid-19

There were a number of early small studies in China and France that claimed the drugs could benefit coronavirus patients.

But it was when President Trump first mentioned it at a press briefing in late March that sparked a global surge of interest in the treatment.

And in April he said: "What do you have to lose? Take it."

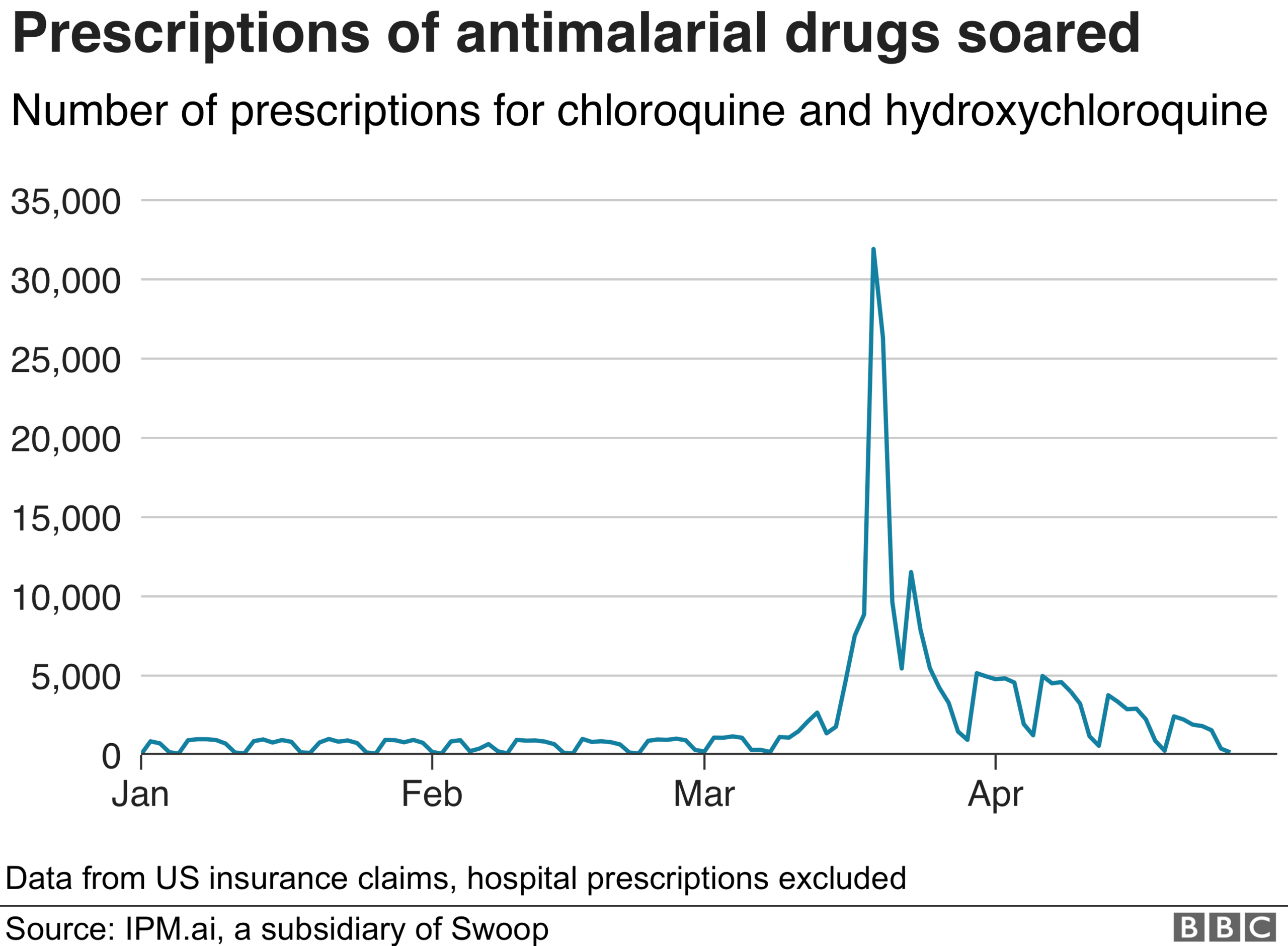

Following the president's first comments, there was a sharp increase reported in prescriptions in the US for both hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine.

Mr Trump revealed in May that he'd been taking hydroxychloroquine as a preventative measure against Covid-19, but later said he'd stopped.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro is another champion of the drug.

He recently said he'd taken it - along with the antibiotic azithromycin - when he became infected with coronavirus.

"We know that there is no scientific evidence, but it has worked with me," he claimed.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

IMPACT: What the virus does to the body

RECOVERY: How long does it take?

LOCKDOWN: How can we lift restrictions?

ENDGAME: How do we get out of this mess?

- Published1 April 2020

- Published27 July 2020