Brexit: Will the UK and the EU co-operate on security?

- Published

Brexit: Theresa May seems unimpressed with Michael Gove's plan

Former Prime Minister Theresa May has told Cabinet Office Minister Michael Gove that the government "should not be resigned to the prospect of no deal" when it comes to post-Brexit police and security co-operation with the EU.

But Mr Gove insisted "there are many, many areas in which we can co-operate more effectively to safeguard our borders outside the European Union", which provoked a bemused reaction from Mrs May that subsequently went viral.

So how will Brexit - especially if there is no deal on future relations with the EU before the end of this year - affect the UK's security co-operation with its nearest neighbours?

Security talks

No-one wants the post-Brexit security relationship to be worse than it was before, but there are technical and legal constraints on what can be achieved now that the UK is outside the EU.

Why? Because the principles of the EU single market apply to internal security and justice just as much as they do to trade, and non-members cannot have as close a relationship as members do.

Once the post-Brexit transition period ends on 31 December, the UK will be out of the single market and such close co-operation will no longer be allowed.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

That means some of the new limits on a security relationship will apply whether or not a deal is done before the end of the year - in particular because the UK refuses to be bound directly by the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice.

But with no deal, things will be even more difficult.

"There's a big difference for security between deal and no deal," says Julian King, the former EU Security Commissioner who was nominated for the job by David Cameron.

"Deal would deliver a dialled down but still valuable relationship. No deal would mean cutting off co-operation on the fight against shared threats, from crime, cyber crime to violent extremism and terrorism."

Data rules

Data protection is an important factor.

If current negotiations on trade and other matters break down permanently, the EU is highly unlikely to agree the UK has equivalent standards to EU rules on data protection.

That is a crucial decision.

"A positive ruling on data does not mean we would retain the full gamut of access to EU databases that we have now," says Professor Anand Menon, director of the UK in a Changing Europe.

"But it would be a lot better than having no deal. A lot of valuable security access could soon disappear."

European Arrest Warrant

There are a number of internal security measures that the UK looks set to lose anyway, even though senior police officers have repeatedly emphasised their importance.

One of the best known is the European Arrest Warrant, in force since 2004, which makes it much simpler to extradite anyone wanted for a criminal offence to or from another EU member state.

It has been a far more efficient process than any other extradition treaty the UK has.

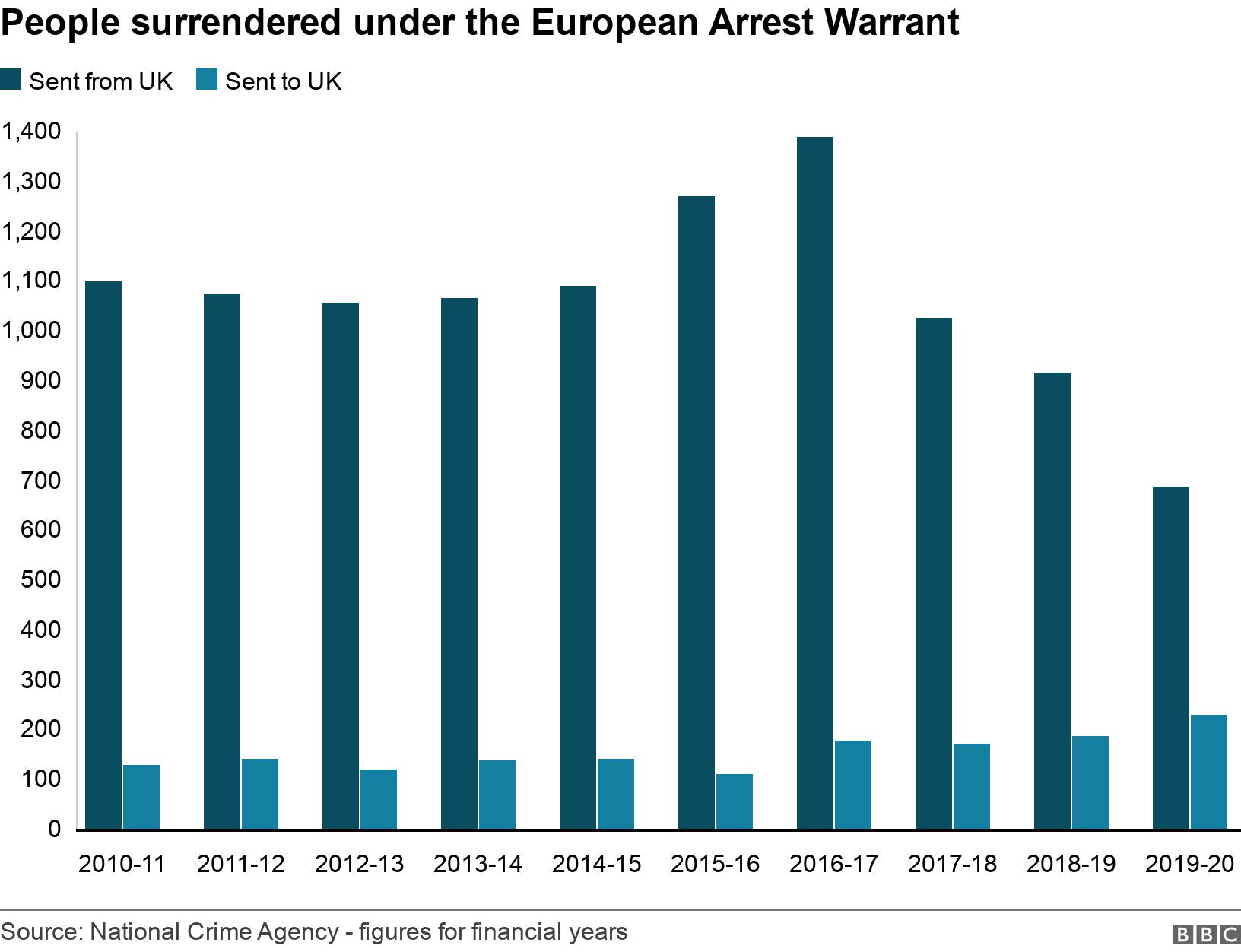

From April 2010 to March 2020, the UK sent back 10,689 people wanted in other EU member states, and it got back 1,564 people wanted for a variety of offences including drug trafficking, rape and murder.

Europol

The UK has always played a leading role in the European police agency Europol, which was founded on British principles. It co-ordinates cross-border police co-operation on things like cyber-crime, human trafficking and counter-terrorism.

No-one is suggesting that such co-operation is about to grind to a complete halt - countries will find a way to work together on the threat from terrorism, come what may.

But Europol has been useful for the UK, and a country can only be a full member if it is in the EU. A non-member can have a close operational relationship with Europol, but that's not quite the same thing.

Data access

Membership of the EU also gave the UK access to all manner of databases related to internal security. Until the end of the transition period, the UK has full access to:

Passenger name records

The European Criminal Records Information System (ECRIS)

The Prum database of DNA records

The Secure Information Exchange Network Application

The Schengen Information System (SIS II)

The Schengen Information System, for example, allows participating countries to share alerts on law enforcement in real time. That means when anyone gets checked anywhere, other countries know about it straight away.

Police officers use it on a daily basis to try to trace people with warrants issued against them, defendants or witnesses absconding from court, stolen cars, missing people or those under surveillance.

Richard Martin, deputy assistant commissioner with the Metropolitan Police. told MPs in July that British officials checked SIS II some 603 million times last year, and everyone involved in security agrees that it is incredibly useful.

But under current rules you can only get full access to SIS II if you're in the EU or in the Schengen area (which allows for passport-free travel between most EU member states and some other European countries).

There are other international databases that the UK will be able to use, but Mr Martin said they would not be as quick or effective as the current "at your fingertips" system.

Mr Martin, who heads up Brexit preparation for the National Police Chiefs' Council, also told MPs that using ECRIS takes about six days to get criminal records from other European countries for suspects in the UK. Without such access, he said, it would take 10 times longer.

What's the problem?

So, if everyone values co-operation so highly, why don't we all simply agree that things will stay the same? After all, a close partnership with the UK, one of the world's leading security powers, is of huge benefit to the EU.

It goes back to the single market aspect of all this: the UK would have to accept some EU rules and regulations. Primarily, the UK would have to accept the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) on disputes over data and privacy, as well as on how the system actually functions.

And the government has said consistently that ECJ jurisdiction of any kind is a red line it will not cross.

Mr Gove emphasised that point again in the House of Commons on Monday, even though he said significant progress had been made in negotiations on security.

The EU could lose too

It is worth remembering that this is a two way street, and the EU also stands to lose invaluable security co-operation with the UK.

In external security, for example, the UK has access to information from the Five Eyes intelligence network which other EU countries do not.

"The EU will be severely impacted by the loss of the UK's strategic relationships with other parts of the world, such as the US and Australia, and its leadership in the field of internal security," says Helena Farrand Carrapico, associate professor in international relations and criminology at the University of Northumbria.

"The UK has been at the origin and forefront of many EU security instruments and initiatives, and there is currently no country in the EU capable of replacing it."

But, she adds: "A no-deal Brexit also implies a decrease in the UK's role as a security leader in Europe and the world."

We asked the Home Office for comment. It says ending free movement of people from the EU gives the UK new opportunities to introduce tougher border rules to make the country safer.

That means, it says, we will be able to set our own rules to help us both stop illicit commodities coming over our border, and prevent people who seek to harm us reaching the UK.

Additional reporting by Anthony Reuben & Oliver Barnes

- Published4 July 2018

- Published19 June 2018