Omicron: What can we learn from South Africa's experience so far?

- Published

A drive-through testing centre in South Africa, where there has been a surge in cases

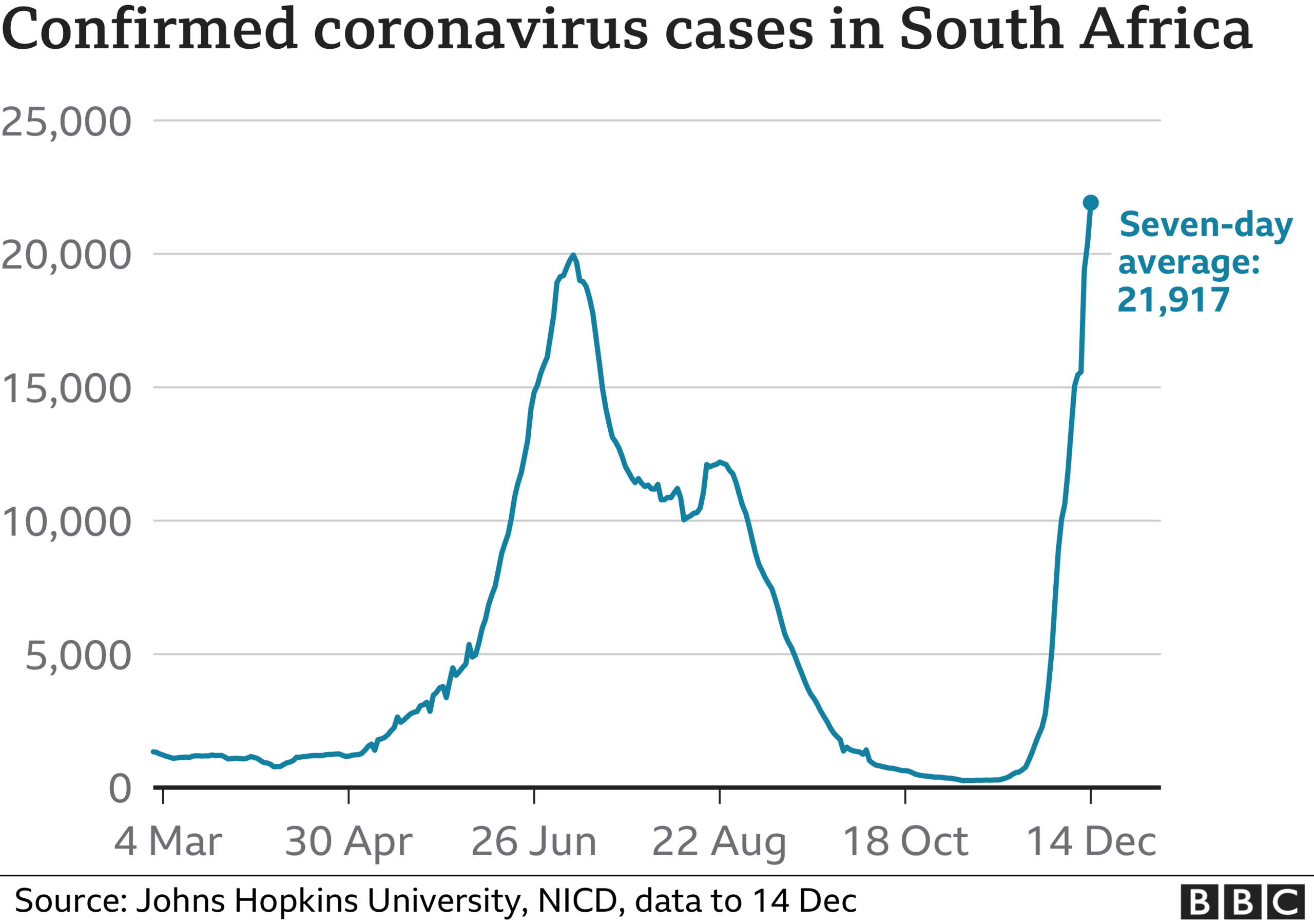

South Africa was where the new Omicron variant was first identified, and cases there have taken off rapidly.

This is starting to be seen in other countries, and the World Health Organization (WHO) says it is "spreading at a rate we have not seen with any previous variant".

What else can we learn from the South African experience?

Does Omicron cause milder disease?

Data on hospital admissions for Covid in South Africa show them rising quite sharply in all provinces.

But they are not going up as fast as you would expect given the number of cases. Fewer patients currently need oxygen and ventilators, and they are in hospital for shorter periods.

Discovery Health, a major health provider there, calculated adults infected early in the Omicron outbreak were roughly 30% less likely to be admitted to hospital than those infected in South Africa's first wave.

Senior South African scientists say this doesn't show the variant itself is milder, though.

The big difference from previous waves is the rate of vaccination and natural immunity in the population.

Although either two doses of vaccine or a previous infection appear much less effective at stopping people catching the Omicron variant, they still seem to provide protection against severe illness.

Dr Vicky Baillie, a senior scientist at Chris Hani Baragwanath hospital in Johannesburg, said the lower rates of hospital treatment were probably because of people having greater immunity

"There's no evidence it's a less virulent mutation," she said.

Early data suggests Omicron leads to fewer hospital admissions than in previous waves

The WHO warns that the data suggesting the variant could be milder could also be skewed by the fact that numbers in hospital are small, and most of those admitted are under the age of 40 - so at lower risk of falling seriously ill.

They may be in hospital for other reasons - but South African hospitals test everyone who is admitted, so pick up a lot of mild cases.

It could also be because over-60s in South Africa are much more likely than the average population there to be vaccinated, protecting them against severe disease.

And South Africa has a young population, with a median age of 27.6 years compared with 40.4 in the UK for example - so its experience of Omicron may not be the same as countries with older populations.

Are more children getting ill from Omicron?

Reports from hospitals in the hardest-hit areas of South Africa - including Gauteng province - show an increase in children admitted to hospital.

Some have pointed to this with alarm, suggesting it shows the variant could be more dangerous for the young.

But it's based on very small numbers and, as with adults, we generally cannot distinguish between children admitted because of Covid, and those discovered to have the virus after being admitted for something else, says Prof Helen Rees at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

Dr Baillie told the BBC her hospital had seen small numbers of children admitted because they were quite ill with Covid, but they recovered in the space of two to three days.

She also points out this data comes from an area where many children are living in poverty, so they may be malnourished and at higher risk from the virus than average.

The proportion of children admitted to hospitals with Covid in Gauteng has also been dropping, from a high of 14% during the first week to 8% in the third week.

What's the role of vaccination against Omicron?

South Africa has relatively low vaccination rates, with 26% of its population fully immunised, so its experience may not be directly comparable to more vaccinated countries. But it does have very high rates of natural immunity.

Dr Muge Cevik, at the University of St Andrews, suggests the risk of infecting others is considerably reduced through vaccination because people will be sick for shorter periods and clear the virus faster, giving it less opportunity to spread.

But it's clear this variant is still spreading fast - even in more highly vaccinated populations.

Few vaccines can completely stop infections, but when it comes to preventing severe disease, the evidence suggests vaccination is still largely doing the job even after this significant mutation.

What's not clear is exactly by how much.

Preliminary studies in South Africa have suggested the Pfizer vaccine prevents roughly 70% of hospital admissions even after two doses several months down the line, increasing to over 90% after a third booster dose.

But South Africa has also used other vaccines, with many receiving the Johnson & Johnson jab, so more research is needed to show how far different vaccines remain effective for different groups.

Additional reporting by Nicola Morrison, BBC Monitoring