Defence spending: Will the government break its promise?

- Published

The prime minister has made a new pledge on defence spending, but there has also been attention on one of his older promises.

At the summit of the military alliance Nato in Madrid, Boris Johnson said the UK would spend 2.5% of its GDP (a measure of the size of the economy) by the end of the decade.

But it has been widely reported that the government is going to break the promise on defence spending that it made in its manifesto in 2019.

The pledge was, external: "We will continue to exceed the Nato target of spending 2% of GDP on defence and increase the budget by at least 0.5% above inflation every year of the new parliament." GDP is a measure of the size of the economy.

We will return to the question of the 2% or 2.5% of GDP - in these times of rising prices it is the inflation promise that is attracting attention.

The prime minister was asked about the pledge on the way to the summit and said: "We are confident that we will meet that. You don't look at inflation as a single data point, you look at it over the life of the parliament and I'm confident we will meet that."

In the manifesto it is clear that they were promising that in every year, defence spending would be higher than the previous year's spending by at least inflation plus 0.5%.

And we know that on current spending plans, external that is not going to be the case.

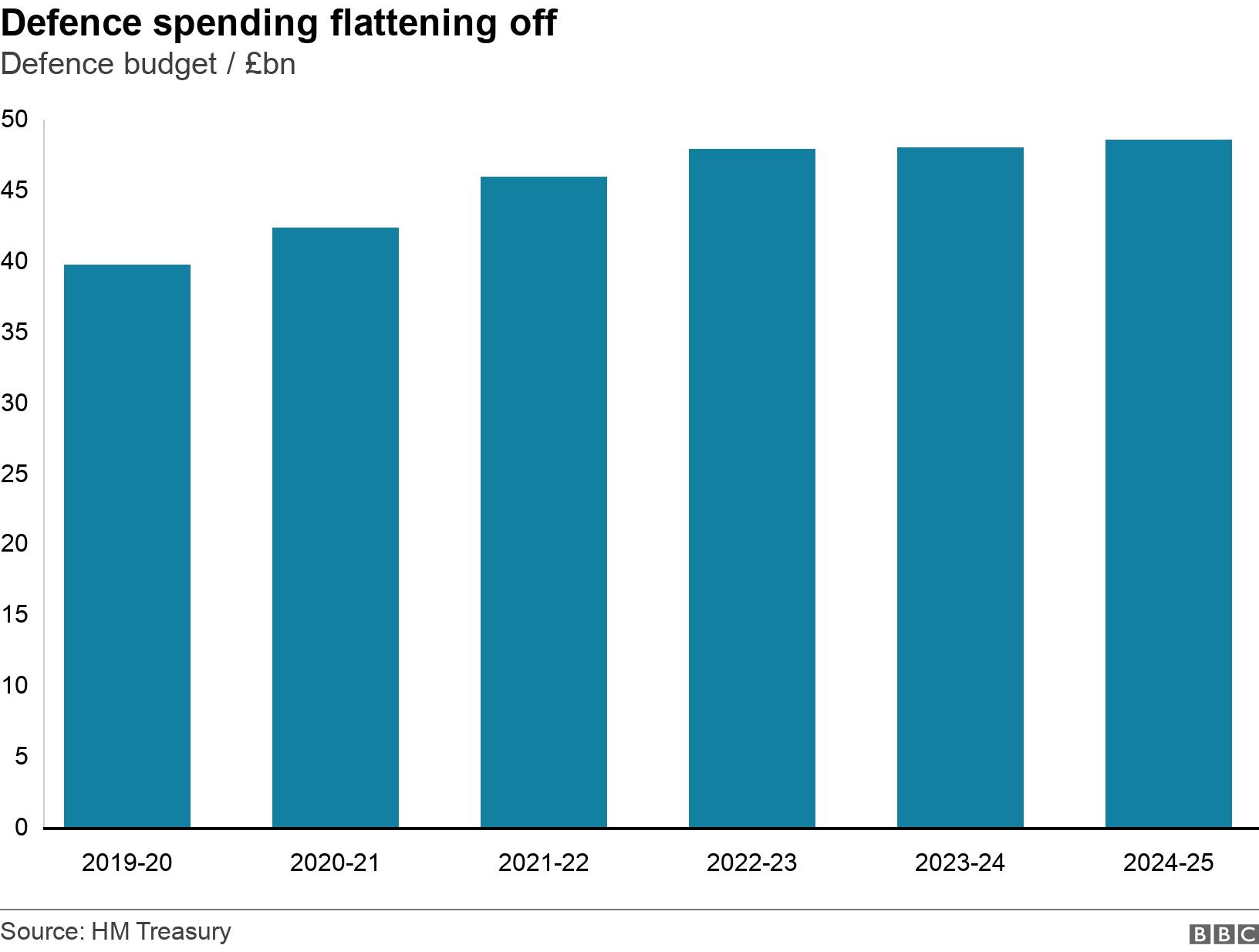

The Treasury said at the time of the Spending Review last autumn that Ministry of Defence spending would fall between 2021-22 and 2024-5 by an average of 0.4% a year after adjusting for inflation.

And inflation expectations have risen since then, which means it's likely to be a bigger fall.

So the pledge has been broken, but that's not the whole story of what has been happening to defence spending.

The prime minister said we should look at spending over the whole of the parliament, which is the period between general elections.

If you do that it turns out that defence spending is expected to increase by an average of 1.5% per year above inflation, which is considerably more than the manifesto promised.

Why is that? It's because the government announced a four year funding deal for defence spending in 2020, which gave a lot of the extra money in the early years.

In other words, if it had wanted to meet its pledge, the government could have spent the same amount of money over the parliament and just kept some of it back to spend in later years.

But that would not have been more helpful for the Ministry of Defence.

Of course, this is all based on spending plans and inflation forecasts - what actually happens over the next couple of years may not be what was expected.

What about the 2% target?

Members of Nato are required to spend at least 2% of their GDP on defence, although only about one third of them do so.

Mr Johnson has said that 2.3% of GDP is currently going on defence (that is the figure for 2021), that the UK would reach 2.5% by 2030 and that Nato should consider raising the target for all members.

That is a slightly different measure of defence spending to the one we have been talking about so far, calculated by Nato itself, which includes some things that are not part of the Ministry of Defence budget.

For example, the spending on supporting Ukraine is coming straight from the Treasury, not from the Ministry of Defence. It counts towards our Nato figure but not towards the departmental budget.

Is it enough?

The pledge to increase defence spending came after Defence Secretary Ben Wallace called for a rise in light of the growing threat from Russia

He was reported to have called for spending of 2.5% of GDP by 2028.

But there is also a question of whether the Ministry of Defence has enough money to fund its activities at the moment, although we do not know exactly how much its costs are rising.

It will be affected by fuel prices, and the costs of military equipment tend to rise faster than the normal rate of inflation. And equipment sent to Ukraine will need to be replaced.

But it is unlikely that the Armed Forces' Pay Review Body will recommend a 10% increase in pay.