Liz Truss: The prime minister's claims about the economy fact-checked

- Published

Prime Minister Liz Truss has defended her government's mini-budget, despite the days of market turmoil that followed it which saw a rise in the cost of government borrowing that has had an impact on mortgages and other parts of the economy.

She told the BBC's Laura Kuenssberg programme that she stood by it but said the government should have "laid the ground better" before announcing the measures, which included tax cuts paid for by billions of pounds of borrowing.

Here are some of the claims Ms Truss made in the interview.

'This is a global problem, we've got Putin's war in Ukraine, the aftermath of Covid and what is happening around the world is that interest rates are rising'

The prime minister said this after being asked whether she felt any responsibility for people's worries about their mortgages, rents and loans.

She's right that interest rates are rising around the world as central banks, like the Bank of England, raise them to fight the inflation that has been made worse by the war in Ukraine.

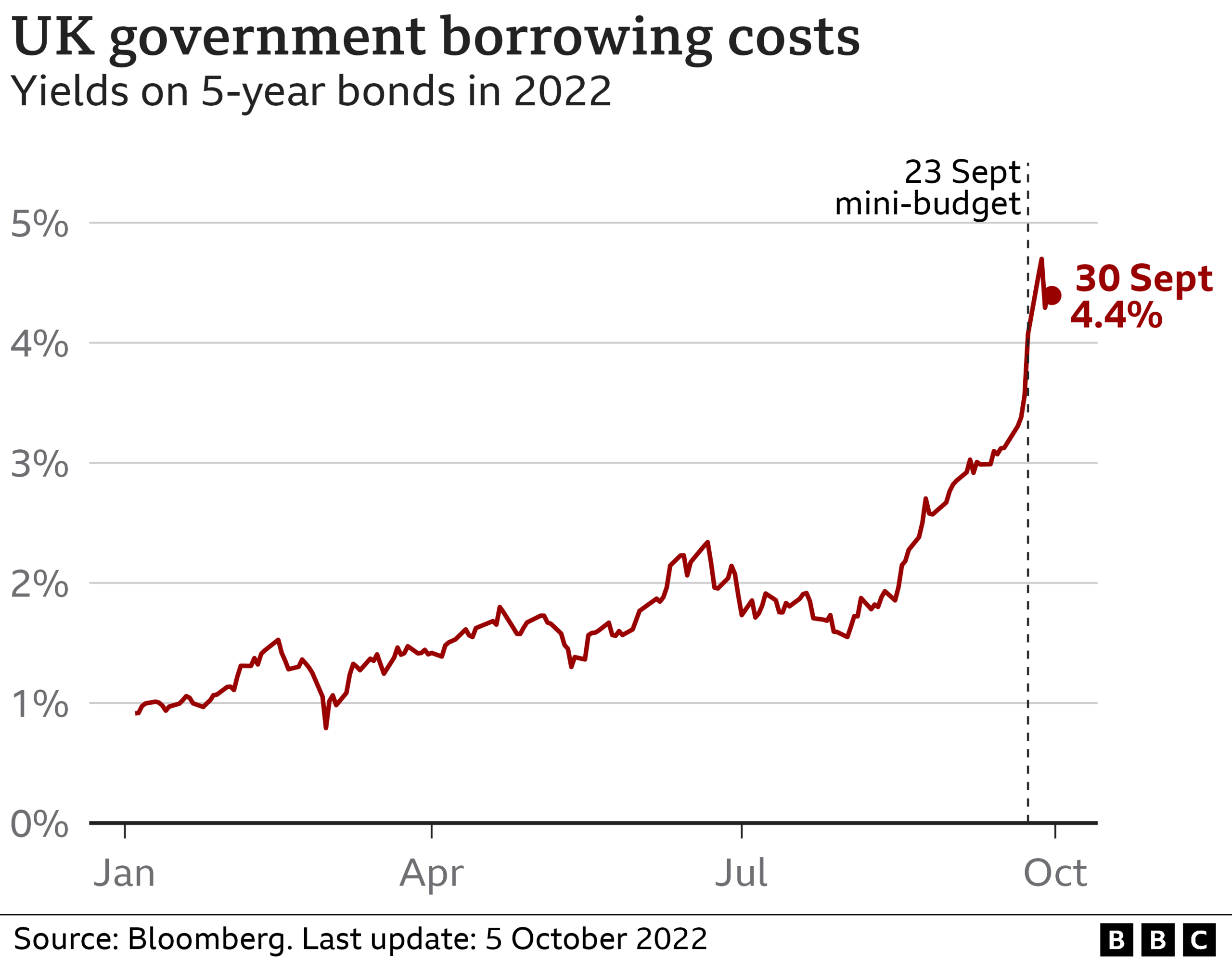

But the cost of UK government borrowing surged to over 4% after the government's mini-budget on 23 September.

As BBC Economics Editor Faisal Islam has pointed out on Twitter, external, this lifted the cost of borrowing in the UK above that in Greece.

This rise was not set by the Bank of England - but by the bond markets reacting to the measures in the mini-budget - and it is feeding through into rising mortgage rates with hundreds of products withdrawn from the mortgage market.

It also had an impact on UK pension funds - which trade in government debt (30-year bonds) - with the Bank of England having to step in to safeguard the sector with a £65bn support scheme.

Speaking on 29 September, the Bank of England's Chief Economist Huw Pill said that over the course of the past week: "There has been a significant re-pricing of financial assets. Part of that... reflects broader global developments... But there is undoubtedly a UK-specific component."

'We've had two decades of relatively low growth'

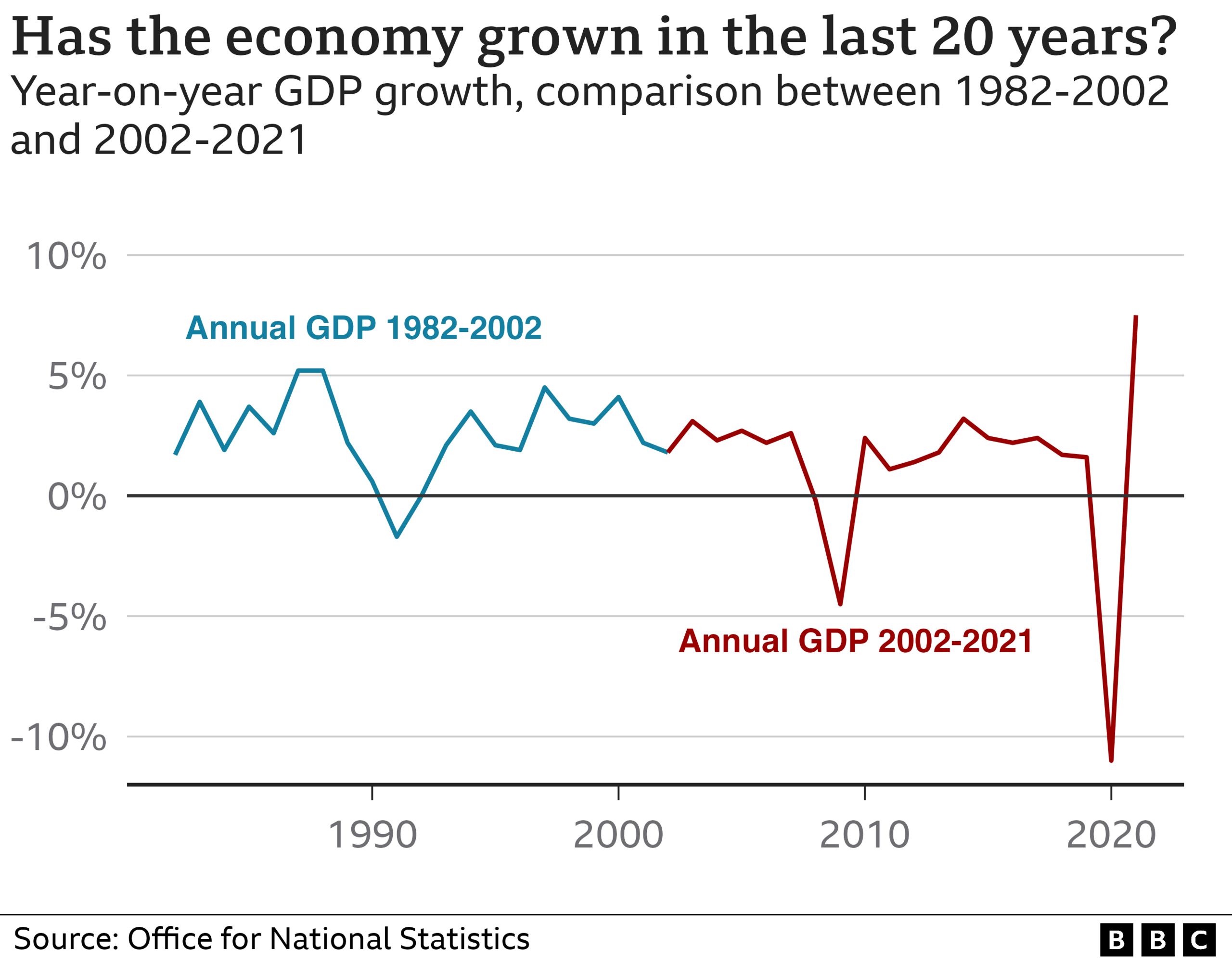

The UK's growth has been low in the past decade, and the decline started before the Covid pandemic.

The UK economy grew at an average rate of 2.3% between 1982 and 1992 and 2.6% between 1993 and 2002.

In the past two decades, the economy has grown by an average of 1.4% each year. But it has been affected by two major global crises - the financial crash of 2008 and the Covid pandemic that started in 2020.

Even if you exclude these, growth in the last ten years has not matched previous decades.

The UK saw an average growth rate of 2.5% between 2002 and 2007 (before the financial crash of 2008-09). In the years after the crash and before Covid - 2010 to 2019 - it grew at a rate of 2%.

Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng have said their goal is to secure steady growth for the UK of 2.5% a year.

'The issue with the OBR is it does take a while to produce those forecasts... we simply didn't have time to go through that process'

The prime minister was asked why the mini-budget had not been accompanied by a forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) - the independent number crunchers who usually mark the government's economic homework.

Market commentators have suggested that its absence contributed to the turmoil over the following days.

Ms Truss claims the government didn't have time to wait for the OBR to produce its forecast.

However, the OBR says it could have done it in time.

In a letter on 29 September, external, Richard Hughes, chair of the OBR, said a draft forecast was sent to the new Chancellor - Kwasi Kwarteng - on 6 September, his first day in the office.

The OBR then offered to provide an updated forecast to be published along with the 23 September mini-budget, but was not commissioned by the government to do so, "although we would have been in a position to do so to a standard that satisfied the legal requirements of the Charter for Budget Responsibility, external enacted by Parliament", Mr Hughes wrote.

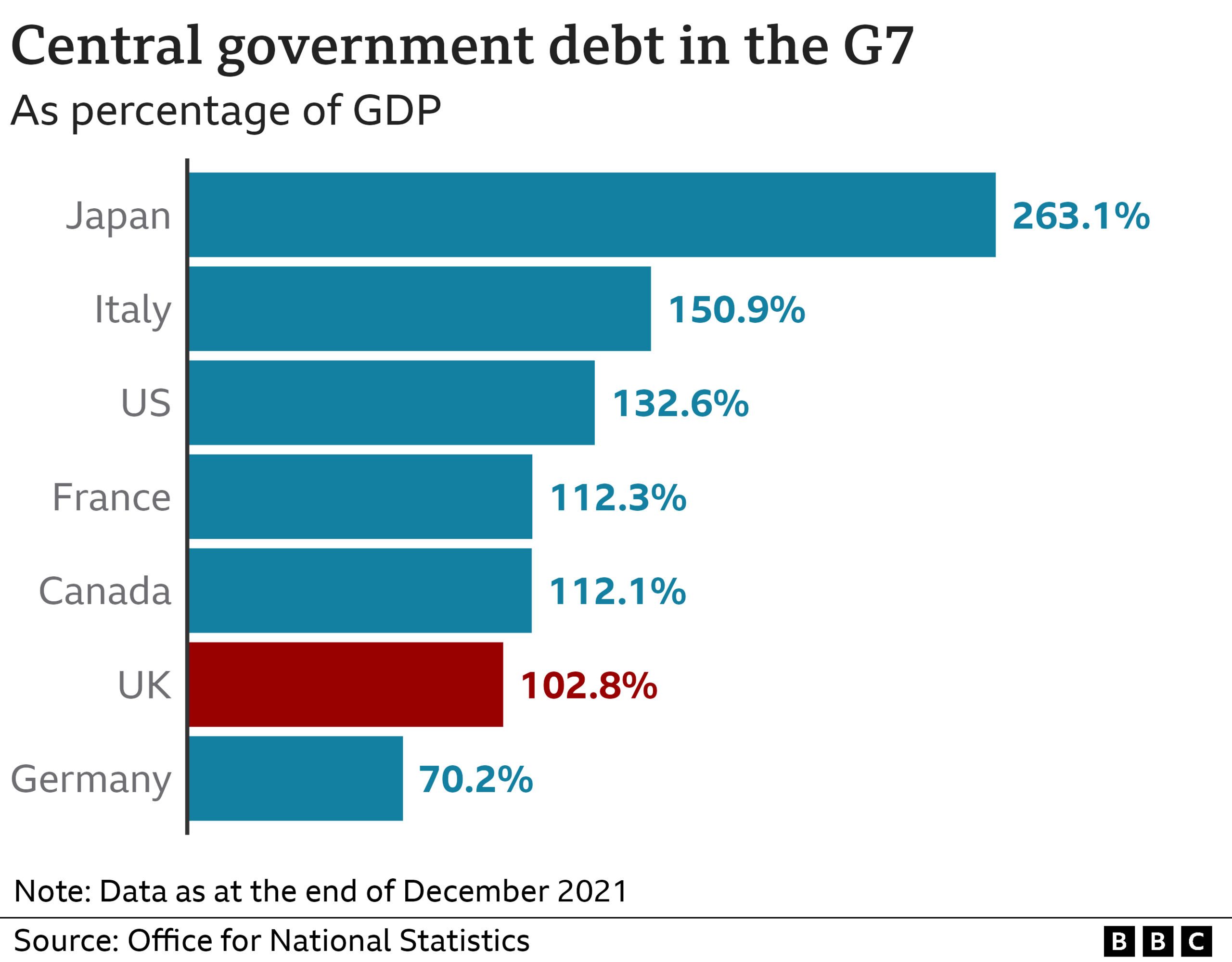

'We have the second lowest borrowing in the G7'

If you look at the government's total debt as a percentage of the size of the economy, this claim is correct.

As of December 2021, the UK had a lower proportion of debt than Canada, France, the US, Italy and Japan, according to the latest data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), external.

Adding the extra borrowing needed this year to fund the measures announced in the mini budget would not lift the UK above the next highest nation.