The hospital washing its hands of sinks

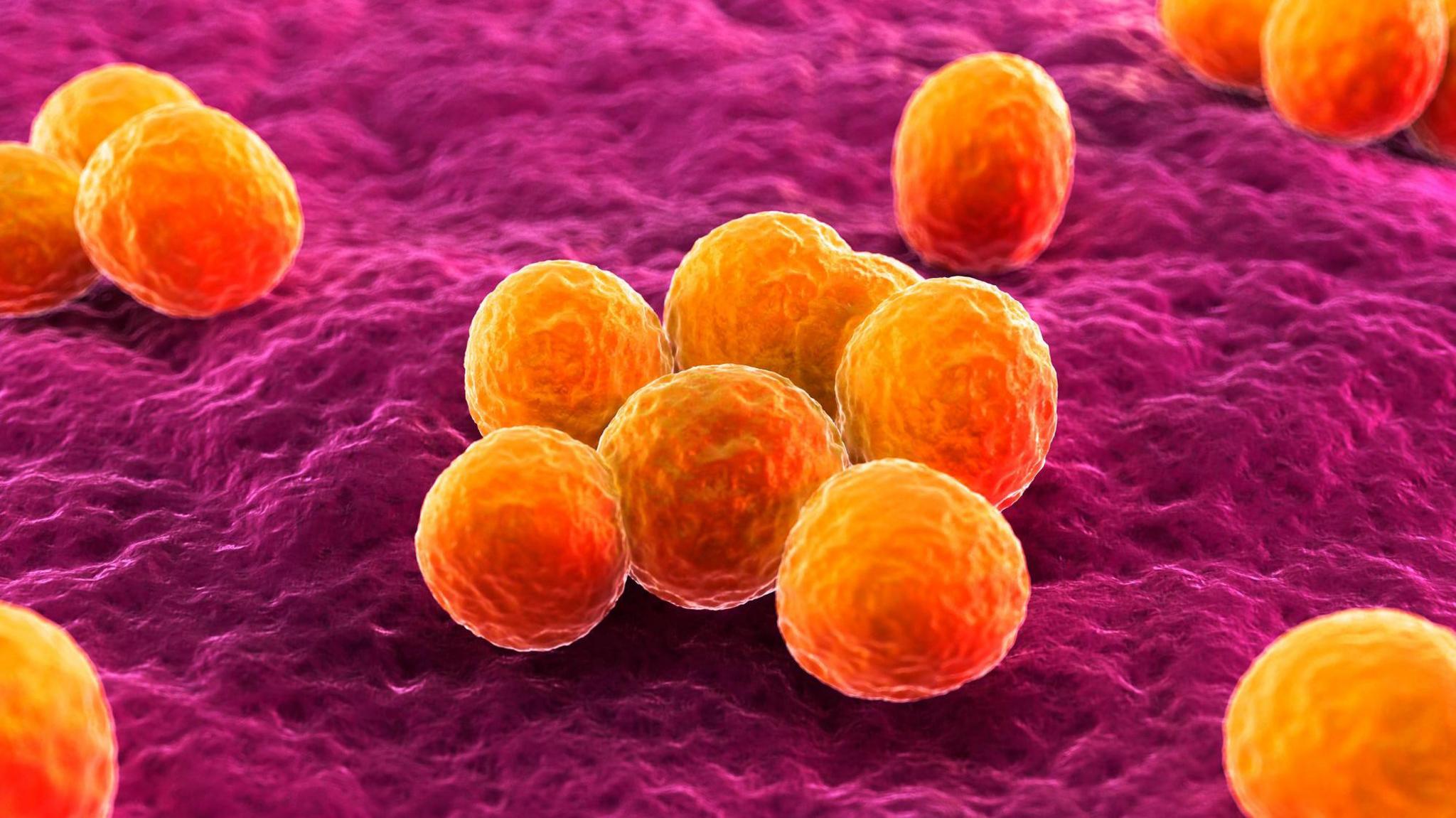

The UK Health Security Agency says the number of people dying because of severe antibiotic resistant infections rose by 4% between 2021 and 2022

- Published

Anti-microbial resistant superbugs have killed an estimated one million people worldwide every year since 1990, according to research.

But Slough's Wexham Park Hospital has worked out that your average superbug loves nothing more than a damp hospital sink, as well as the drains and waste pipes that come with them.

In what's thought to be the first experiment of its kind in the UK, it has removed nearly all of the sinks on its intensive care unit to minimise the risk to patients from water-borne contamination.

Wexham's bosses say it could help turn the tide in the battle against superbugs.

In a world where hand washing has long been deemed the best way to keep hospital wards free of infections, it may sound counterintuitive.

But not according to Dr Manjula Meda, a consultant microbiologist at the Frimley Health Trust, which runs Wexham Park.

"Previously we said washing your hands is the single most important thing you can do to protect patients," she said.

"But we now know that washing hands is ineffective in the majority of instances because people don't do it properly.

"For it to be effective you have to wash your hands thoroughly for 20 seconds and then dry them properly afterwards, something most people don't do."

Dr Manjula Meda says we need to completely change the way we think about controlling infection in healthcare environments

Walking around the Slough hospital's intensive care unit, where patients are highly vulnerable to infection, it's no surprise that everything is spotlessly clean.

The sheets are pristine white, there are no rubbish bins in public view, and bottles of hand sanitisers are everywhere.

All but a couple of the unit's sinks have been removed to reduce the risk of contamination, and the ones that do remain look nothing like the ones we're used to seeing.

One of the few remaining sinks on Wexham Park Hospital's intensive care unit

There's a tap coming out of the wall, but you don't set the water running by physically turning anything on.

Rather you sweep your hand under a sensor to get things moving and there's no basin underneath this faucet.

That means no drain and no waste pipe, two locations identified by the hospital's microbiologists as superbug hotspots.

For nurses wanting to wash a patient in their bed, this means putting a bowl under a faucet with a plastic sleeve wrapped around it, to limit any water-borne splashes from the slowly running water.

After washing their patients they then have to carry away the waste water and wipes they have been using.

They are then disposed of safely elsewhere, away from the intensive care unit and its often immunocompromised patients.

Wexham Park Hospital says its water-safe project could help the NHS stay ahead in its fight against superbugs

Dr Meda says: "If you want to control these bugs it has to be in hospital settings, because waste water is a super reservoir for these superbugs.

"Changing practices that we are pioneering at Wexham Park could be one of the ways we start to win the battle against these bugs."

The hospital says its initial surveillance shows that removing sinks hasn't compromised anyone's safety, while it has started to reduce many types of hospital-acquired infections.

Hospital bosses are so convinced that they're onto something, they are now rolling out their new "water-safe" approach to other wards.

And last week a medical team from Japan flew over to see what they could learn from Wexham's project.

While the government's NHS Hospital programme, which is looking at how it can build more than 40 new hospitals over the next decade or so, is also showing an interest.

The Slough hospital's microbiologists hope their work could act as a blueprint for the wider NHS.

Get in touch

Do you have a story BBC Berkshire should cover?