Three perspectives on how to fix social care

Pat was diagnosed with dementia in 2010 and her health declined whilst in nursing care

- Published

One in five care homes in England is now rated "requires improvement" or "inadequate" by the watchdog the Care Quality Commission (CQC). In one home, a resident fell 32 times in only 11 months. The new Labour government says it wants to set minimum standards for social care as well as pay and conditions for carers.

The BBC has been speaking to three people with experience of life in care homes to hear what they think needs to change for standards to improve.

Ashleigh Joachim's mother Pat was in her 60s when she was diagnosed with dementia.

When the disease progressed and Pat moved into a care home, both Ms Joachim and her sister Lesley Haswell, from Sunderland, were determined their mother would receive the best care available. The home they chose was rated "good".

So, when they noticed a decline in what they call "the basics" - Pat being clean, comfortable and well fed - they pointed it out to staff.

Pat, in 2016, was sometimes taken out for family lunch whilst living in residential care

"We noticed my mother was in dirty clothes with unclean teeth, nails with faeces in, not helped to feed, upset a lot of the time," Ms Joachim said.

"We'd complain to the staff but things weren’t improving - they were deteriorating."

The sisters started keeping a log and looked at their mother's care files, which they said were not always accurate.

At that point, care home staff were "very clearly unhappy we were complaining" and seemed resentful, Ms Joachim said.

'Dehydrated and dirty'

The family escalated their complaints until Pat was moved to another care home where, Ms Joachim said, the same cycle began again.

"It was decent for a few months, then the manager left and the care deteriorated," she said.

"Mam had a broken nose nobody could explain, she lost 20kg [about three stones] in weight, was left without medication. She was clearly dehydrated and she was dirty."

Concerned they could not be sure their mother was safe, the family moved Pat to yet another home.

"Next care home, same thing," Ms Joachim said. "It had a good CQC rating, but she's still dirty and she's losing weight.

"The care files are inaccurate. Same cycle, but my mother is getting worse."

Pat's family began documenting any failings in her basic care, from dirty clothing (left) to unexplained injuries not detailed in her care file (right)

One former care worker at other homes in the north-east of England, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told the BBC she received minimal initial training. A lack of staff during her induction meant she felt the pressure to hit the ground running, she said.

"We would need to toilet, dress, feed over 50 residents with just six carers, whilst the seniors did the medication rounds," she said.

"By the time you had finished the bedrooms, done the tea round to make sure residents had plenty of fluids, updated paperwork and toileted residents, it was time for lunch."

Pat's family documented unexplained injuries in another care home in 2016

The carer said time pressures and a shortage of staff were compounded by employees suffering assaults on a regular basis.

"I have seen staff who have been slapped, punched, hair pulled out and even a fractured skull," she said.

"I have often had to send a staff member out to cool down."

Residents with dementia would refuse to be changed and staff had no choice but to leave them.

"You can’t physically force them, it would be abuse," she said. "So you would just keep going back between other jobs, trying to encourage the resident to let you help.

"Meanwhile I have had health professionals and families accuse you of not looking after the resident and leaving them wet."

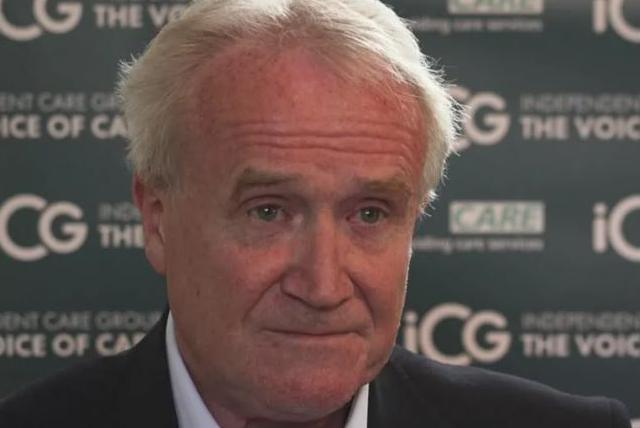

Mike Padgham runs the Independent Care Group which supports care providers including care homes

The carer was sometimes so uncomfortable with situations she witnessed at work, including patients being forced from their beds, drag-lifting and even a member of staff high on prescription drugs, she decided to raise the alarm.

"I did whistleblow, but I was treated like a problem-causer, like I had done something wrong," she said.

"I left shortly after that."

Mike Padgham, who chairs the Independent Care Group which supports care providers, said the vast majority of homes were providing good care but should be open to feedback.

"Complaints should be viewed as positive," he said.

"What provider gets up in the morning to provide poor care? If you raise a problem or whistleblow, you should be encouraged."

Mr Padgham added that a lack of staff was a huge issue across the industry.

"Across England, there's 152,000 vacancies," he said. "By 2035, we need 440,000 extra staff in social care."

What needs to change?

Mr Padgham said he would like to see "bold" action from the new government.

"We’d like to see wholesale reform including, potentially, care being brought into a national care service, alongside the NHS," he said.

The former care worker said alleviating the pressure on care home staff was key if the government wanted to change things for the better.

"I really liked my role as a carer, I like to think I made the residents' lives better," she said.

"I left because it is very low pay, very physical and I struggled morally with rushing the care of the residents to keep up with demands of the job."

The CQC said its main priority was "to ensure the health and wellbeing" of care home residents.

"This includes listening to what they and their loved ones tell us about services, to help us decide when and where to inspect, ensuring we have the full picture about the level of care being provided."

The body said it did not have legal powers to investigate individual incidents but could investigate and prosecute "provider level failings" under the Health and Social Care Act.

Pat's daughters say CCTV and electronic care logs are the only way to ensure complete transparency

Pat died in 2017, but her daughters still want to see changes.

They want CCTV in residents' rooms so there can be no doubt when it comes to issues like falls and questions around basic care.

They would also like to see a "care charter" introduced to offer people living in care homes a list of guaranteed rights.

"Let's face it, if these were babies there would be uproar," Ms Joachim said.

"Why aren’t we protecting our older people?

"We were fighting for our mam. What about all those people who don’t have anyone fighting for them?"

- Published9 July 2024

- Published23 June 2024

- Published25 June 2024