Survivors' tales from the deadly Great Gale

The Cobb, pictured during Storm Eunice in 2022, is now home to Lyme Regis Aquarium

- Published

The date is 23 November 1824 and up to 100 people have been killed in a hurricane-force storm lashing England's south coast.

In Lyme Regis, a terrified elderly couple are cowering inside the Customs Watch House on the Cobb breakwater.

Harbour pilot William Kerridge and his wife clambered in through a window as their cottage next door was swept away.

With the buildings only accessible at low tide, it would be two days and nights until the storm subsided and they could be rescued.

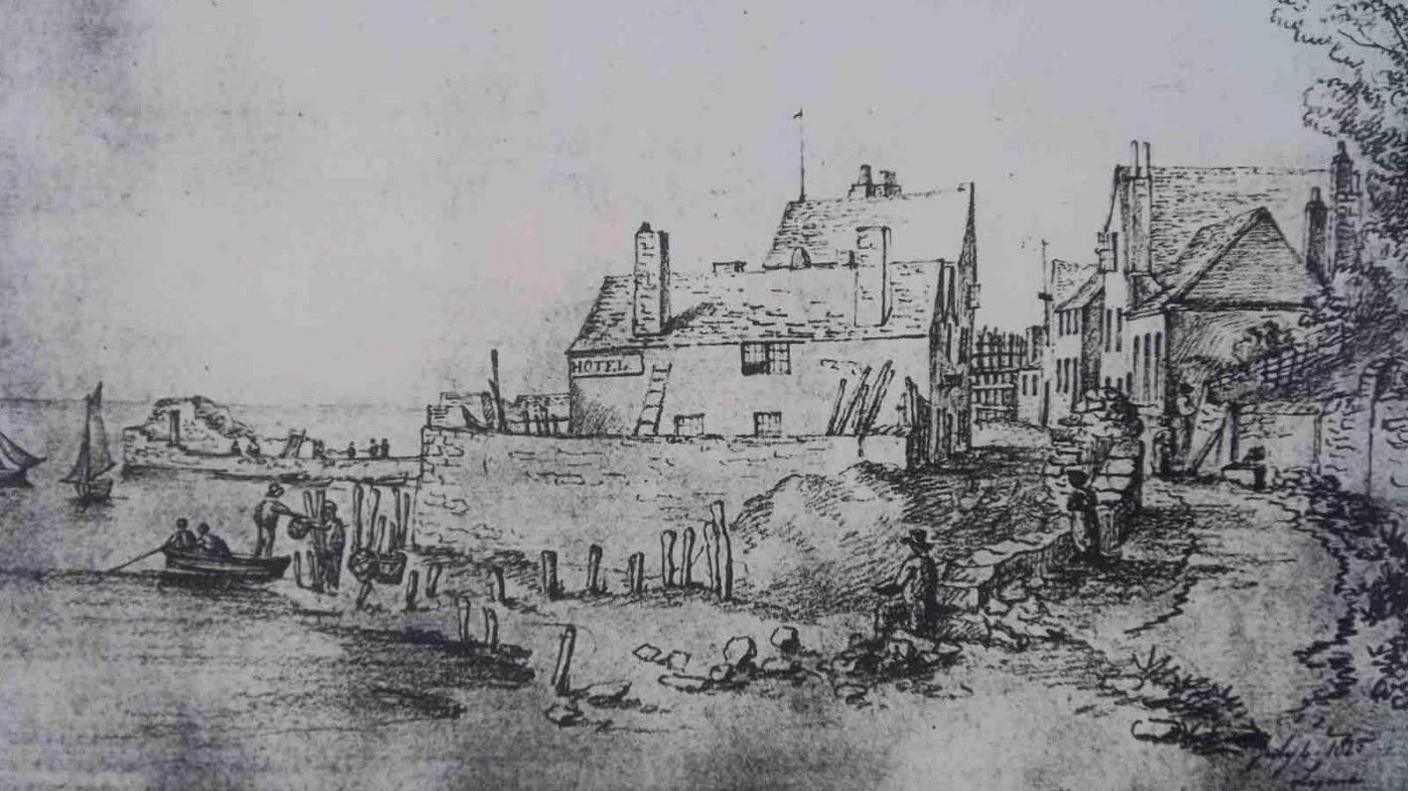

Wooden piles were all that remained of houses on the shore near The Cobb

The Great Gale hit the coast on the night of 22 November. Dorset was the worst affected but communities were flooded from Kent to Cornwall.

The Kerridges' ordeal was documented by local schoolmaster George Roberts in 1834, who said the couple also witnessed the death of two men in a revenue tender swept out of the harbour.

"Their situation was dreadful," he wrote. "They saw the death of the men in the revenue vessel.

"They saved themselves by getting out at the back of their dwelling, and then into a window of the watch house belonging to the customs, where the man scuttled the floor and saved the house.

"His dwelling was destroyed. There was no staying on the quay for the sea."

Anning's letter was documented in Hatchards Memoirs of the Life of FA Bell by Rev Grant

When the Kerridges eventually emerged, a 90-metre section of the Cobb had been destroyed and low-lying houses on the shore had been reduced to rubble.

The aftermath was described in a letter from fossil hunter Mary Anning to her friend, Frances Bell, in London.

"Oh, my dear Fanny," she wrote. "You cannot conceive what a scene of horror we have gone through at Lyme, in the late gale.

"A great part of the Cobb is demolished, every vessel and boat driven out of the harbour, and the greatest part destroyed, two of the revenue men drowned, all the back part of Mrs England's houses and yards washed down, with the greater part of the hotel, and there is not one stone left of the next house.

"Indeed, it is quite a miracle that the inhabitants saved their lives."

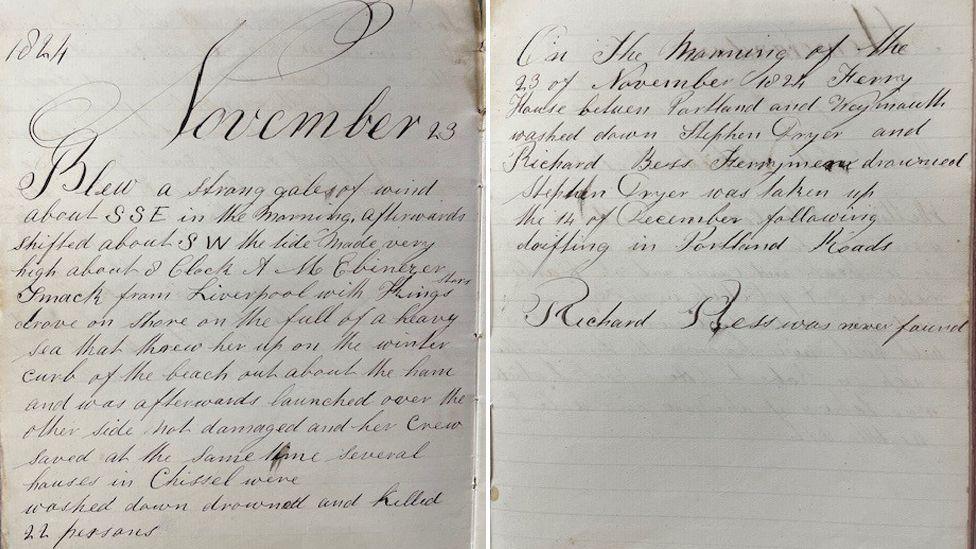

John Thomas Elliott of Weston said two ferrymen drowned but only one was found

Similar scenes of horror played out along the coast at Portland, where part of the village of Chiswell was destroyed.

"Several houses in Chiswell were washed down, drowned and killed 22 persons," wrote Weston resident John Thomas Elliott in his diary.

"On this morning of 23 November 1824, Ferry House between Portland and Weymouth washed down."

Elliott said both of the ferrymen drowned but only one was ever found.

The following day, he noted: "A Dutch galleon ran on shore opposite the Ferry. Her crew was all drowned."

Chiswell, pictured here in 2014, has been battered by storms for centuries

In Sidmouth, cottages on the esplanade were destroyed and many more homes were flooded.

In Plymouth, 22 vessels were sunk and more than 200,000 tons of stone was swept away from the city's breakwater, which was still under construction.

According to historians, the tide did not return to normal until after Christmas and it took years for coastal communities to recover.

Experts say the storm was caused by a rare combination of factors - hurricane force winds, spring high tides, extreme low pressure and towering waves.

A photo from November 1924 shows the aftermath of tidal wave flooding in Chiswell

Andrea Summers, Environment Agency flood and coastal risk manager for Wessex, said the anniversary served as a "stark reminder of the destructive power of nature" and "highlighted the importance of being prepared".

She said: "We are much more resilient now, with major innovations in forecasting, warning and defence systems but our climate is changing and extreme weather events are becoming more frequent."

An exhibition, featuring more personal accounts from the storm, can be seen at Portland Community Venue in Fortuneswell until 16:00 GMT on Sunday.

Arts organisation B-Side, external is hosting events, including poetry, talks, a craft workshop and a storm-themed open mic night.

Get in touch

Do you have a story BBC Dorset should cover?

You can follow BBC Dorset on Facebook, external, X (Twitter), external, or Instagram, external.

- Published25 October 2024

- Attribution

- Published22 October

- Published31 January 2021